Expanded access to voting yielded huge turnout. Will states take it away?

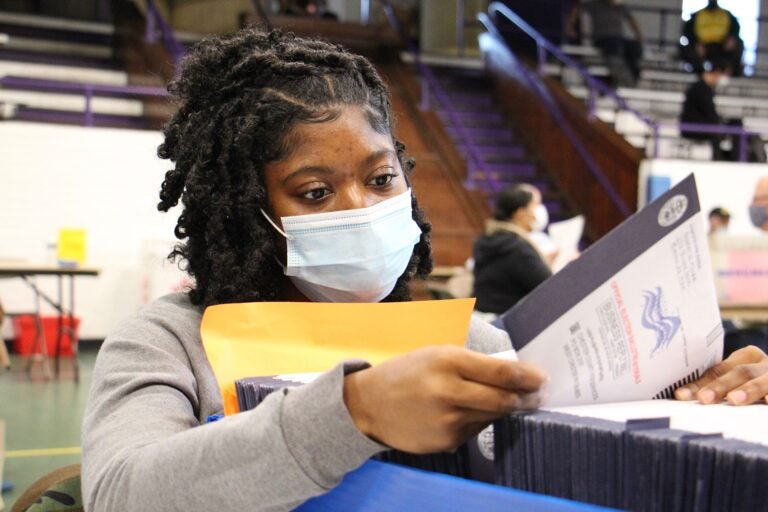

Chester Country election worker Jessica McPherson inspects ballots in the West Chester University gym, where all county mail-in ballots are being counted. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Jennifer Morrell understands more than most that when voters experience new ways to vote, it’s not easy to take them away.

When Morrell was overseeing elections in Utah’s Weber County, it offered what was going to be a onetime, all-mail election to decide a library bond issue.

“People were surprised at turnout, I do remember that,” said Morrell, now an elections consultant.

For the following election, a municipal race, the county went back to its standard model. People called her office flabbergasted.

“Voters were saying, ‘You mailed me a ballot over the summer! Why didn’t I get one now?’ ” Morrell said. “There were enough calls that we took note. It wasn’t just a few calls.”

Utah is now one of a handful of all-mail ballot states. And election officials across the country may be faced with similar phone calls in the upcoming year.

From pandemic to permanent?

For 2020, nearly every state did something to make voting easier in response to the pandemic, whether that was easing restrictions on who could vote by mail, or sending mail ballot request forms, or ballots, to all registered voters.

Those changes helped propel the country to its highest turnout election in over 100 years, one that experts say was administered well and which officials have called highly secure — despite baseless criticism by President Trump.

“You had people running the largest mail elections they’d ever run, but also needing to make polling places as safe as possible for election workers, for election officials and poll workers and voters,” said Ben Hovland, chairman of the federal Election Assistance Commission. “They were able to do that remarkably.”

Soon, however, state governments will have to decide which of those changes to keep and which to discontinue as planning gets underway for forthcoming races around the country.

In other circumstances, it might have been a safe bet that expanded access would become standard.

“Voters — people in general — have busy lives, they work different schedules,” Morell said. “I think suddenly when you give them the opportunity to vote in a way that is convenient, I think they do want to see that become the status quo.”

But these remain unusual times.

Lasting impact of rhetoric

If Democrats generally support reforms that give people more opportunities to vote, the big question ahead is how willing Republicans across the country are to go along.

Views about elections and democratic practices always have been partisan. This year that atmosphere has become supersaturated. And Trump’s efforts to undermine confidence in vote-by-mail systems may affect what lower-ranking Republicans practically can support, say voting officials and experts.

Kim Wyman, the Republican secretary of state of Washington, which is an all-mail ballot state, says she is already fielding a push from other Republicans in her state who want a move back towards precinct in-person voting options due to unfounded fears about widespread fraud.

Officials in states that expanded early voting or mail voting may feel similar pressure in the upcoming year, she said.

“It’s going to be up to the political makeup of those [state] legislatures, and whether they believe it was a good experience or not is going to drive that,” said Wyman. “It always has been political. Let’s face it — the people that get to write the laws on how we conduct elections are the people that are elected by that system.”

Complicating matters are results in 2020 that challenged an old argument in politics that says greater turnout automatically favors Democrats. It was never that simple and the reality remains complex.

Wyman was reelected this year in a state that went for President-elect Joe Biden, and Republicans nationwide had more election successes than often predicted. They were able to hold onto competitive senate seats in Maine and North Carolina, both states that made pandemic-related voting changes, and the GOP also did well in state-level elections.

For Republican state legislators and elections officials, that raises a tough question: Should they preserve expanded access because it has shown that growing the pool of voters can help them? Or is taking that position too politically risky?

Political pitfall

Some political figures already have been caught in this trap.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, has defended the integrity of his state’s election after Biden’s victory there. But after weeks of accusations by the Trump campaign and other prominent Republicans, Raffensperger alluded Friday to wanting to make changes that may make the vote-by-mail process more difficult.

“We want to take away any concern that you could have about fraud,” he said in an interview with Georgia Public Broadcasting‘s Stephen Fowler. “And we need to do that with an objective measures, not subjective, whenever we can.”

In Washington, D.C., where many Republican members of Congress have yet to acknowledge Biden’s victory, there is still skepticism over the motivations behind all the voting changes nationwide.

“We saw COVID being used in certain states to politicize the elections process and nuclearize procedures that were used for a partisan gain,” said Rep. Rodney Davis, R-Ill., the ranking member of the House Administration Committee.

Davis said he was fine with voters being able to request absentee ballots, but that he opposed expansions of systems that sent a ballot to every registered voter.

What may happen on Capitol Hill?

Despite the Russian attack on the 2016 presidential election and the huge attention that brought to election security over the past four years, Congress declined to pass much major election-related legislation.

Lawmakers did send almost $1 billion to states to improve their election security postures — but they passed no new laws mandating backup paper ballots or other minimum requirements that cybersecurity experts recommended.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., hopes that under Biden, that will change.

“It is the big question,” she told NPR in an interview.

Klobuchar is the ranking member of the Senate Rules Committee, which has jurisdiction over federal elections. Two years ago, she co-sponsored an election security bill with Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., which seemed to be gaining momentum before the White House, under Trump, swooped in and pushed for Republicans in the Senate not to move forward with it.

Under a Biden presidency, Klobuchar said she was more optimistic.

“Despite the fact that the Republican Party has been walking us down voter suppression lane for a long, long time … people have fought back big time,” she said. “And then you have the fact that you do have some Republicans who have been willing to play ball to make it easier for people to vote. All of that gives me some hope we can put in some minimum standards.”

Some Republicans, including Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Mo., have indicated a willingness to send more federal money to support local election officials. Decisions like that may be less controversial over the coming years, compared to the past four years, when every election-related decision could potentially trigger backlash from Trump.

Hovland, of the Election Assistance Commission, says he just hopes there aren’t residual effects of this month’s election conflicts — the claims by the outgoing president and some supporters that the results aren’t legitimate.

It’s clear, Hovland says, that voters want more voting options, and officials shouldn’t use fraud without evidence as a reason not to give those to them.

“There’s been a long track record of people using baseless accusations about fraud to enact policies that are anti-voter, that keep people from participating in the process,” said Hovland. “I certainly hope we don’t see that following this election, and this rhetoric that we’re seeing right now.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))