Before he animated for Disney, he sketched cartoons in an internment camp

Father and son artists, Vince Ito (left) and Willie Ito, at their StoryCorps interview in Los Angeles last month. (Rochelle Hoi-Yiu Kwan/StoryCorps)

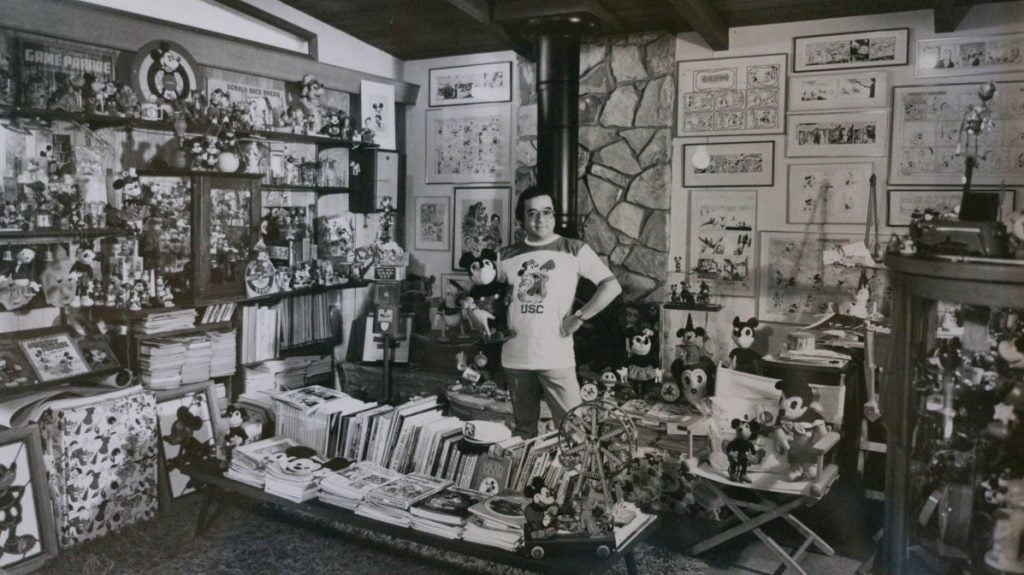

Willie Ito, 85, wanted to be an animator from the moment he first saw Snow White in theaters as a young boy.

“I remember the seven little men walking across the screen, singing, ‘Heigh-ho, heigh-ho!’ and I thought to myself, ‘Wow, that’s what I want to be.’ Not one of the seven dwarves, but an animated cartoonist,” Willie told his son, Vince Ito, 60, at StoryCorps last month.

But when Willie was 8, those dreams looked dim. During World War II, Willie’s family was among tens of thousands of people of Japanese descent — most of whom were American citizens — who were forcibly removed to internment camps. In 1942, two months after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that gave the military clearance to incarcerate those perceived as a potential threat. In reality, there was little-to-no evidence of actual subversive activity among the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated.

Willie tells Vince he’ll never forget arriving at the camp in Topaz, Utah — with its rows of tar-paper barracks — from their home in San Francisco. “The dust was whipping up like fine talcum powder and I remember looking at my grandfather, who had on his dark overcoat and fedora,” he recalled to his son. “And it was all white with dust.”

Despite his barren surroundings, Willie managed to develop his skills as an artist. The internees would order basic necessities from Sears and Roebuck — and would often save the leftover catalogs to build a fire in the cold Utah winters. Willie would doodle on the margins of those catalogs to make flipbooks of his drawings.

“My imagination would just run amok,” he said.

Willie and his family were released in July of 1945, three months before the Topaz camp would close.

At age 19, Willie got his first interview at Disney Studios.

“I stepped into the elevator, and as the door was closing, it suddenly swung open, and standing before me was Walt Disney himself. As Walt stepped in, he nodded,” Willie said. “I was thinking to myself, ‘Oh, my God.’ ”

As a Japanese American, Willie didn’t expect to run into other Asian Americans in the Hollywood animation community.

“I always perceived Walt Disney as sort of a lily-white studio,” he said. “But a Japanese American, Iwao Takamoto, walked in and says, ‘We love your work. You’re hired.’ And I’m thinking, ‘This can’t be true!’ ” Takamoto would go on to become Willie’s friend and mentor for many years.

Willie was told he’d get started working in the “Lady unit.”

“Back then, the studios had inking and painting department with nothing but ladies working in it,” he said. “So I thought, ‘Well, that must be the entry level. Then when you cut the mustard, they’ll move you up into animation.’ ”

He was mistaken. Lady was actually short for Lady and the Tramp. As it turned out, Willie had been assigned to work on the film’s iconic spaghetti kissing scene.

“If I’m in front of a blank sheet of paper with a pencil, I find such solace,” Willie said.

His passion and work ethic inspired his son to pursue a career in art, and Vince now works as a graphic designer.

Willie also worked at Hanna-Barbera for 14 years — animating shows like The Jetsons and The Flintstones — and eventually came back to Disney, where he officially retired in 1999 as the director of Disney character art international.

“When I came to Los Angeles to seek my fame and fortune, it was quite intimidating,” he said. “But I knew, by hook or crook, this is what I want to do, and today I am very proud of what I did.”

Audio produced for Morning Edition by Mia Warren.

StoryCorps is a national nonprofit that gives people the chance to interview friends and loved ones about their lives. These conversations are archived at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, allowing participants to leave a legacy for future generations. Learn more, including how to interview someone in your life, at StoryCorps.org.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))