Gnawing question for former Philly teacher: Did my school make me sick?

As anxiety mounts over the condition of Philly schools, many teachers wonder if their buildings made them sick. Lynn Johnson is one of them.

Listen 20:58

Lynn Johnson, a former teacher at Franklin Learning Center in Philadelphia, developed a rare auto-immune disorder that forced her to retire at 55. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Listen to The Why wherever you get your podcasts:

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | RadioPublic | TuneIn

On the day before Thanksgiving in 2015, veteran biology teacher Lynn Johnson made an unusual decision — she decided not to clean up her classroom.

Her students had just completed a lab experiment, which would typically send her into a frenzy of tidying and straightening. But she’d felt off all day. Her body wouldn’t let her clean.

“My head felt kind of tipsy — almost like I was drunk,” Johnson said.

So instead of gathering the test tubes and beakers and thermometers, she left the space as it was — frozen in a state of suspended discovery.

Then the 55-year-old flicked off the lights in Room 217 and walked out of Franklin Learning Center, the Philadelphia high school where she’d taught for 16 years.

“I said,`I’ll just take care of that when I come back Monday,’” Johnson remembered. “I never came back Monday.”

Johnson didn’t know it then, but her teaching career had just ended.

The next six months would take her on an odyssey to the edges of medicine — to the brackish place where science meets mystery. She would lose her hearing, her balance and, eventually, her independence.

Those six months would flip Johnson’s life, and leave her with a gnawing question:

Did my school building do this to me?

A pressing question

That question confronts many Philadelphia teachers — now more than ever.

In September, the city’s teachers union announced that one of its own — 51-year-old special-education instructor Lea DiRusso — had been diagnosed with mesothelioma.

Mesothelioma is caused, in virtually every known case, by exposure to asbestos — a toxic mineral once commonly used in insulation and other building materials. DiRusso worked for decades in two Philadelphia schools that had asbestos inside them, making it clear there may have been a link between her illness and her job.

DiRusso’s diagnosis presaged a flood of media coverage on asbestos and other potentially toxic substances inside Philadelphia’s public schools. It spotlighted the human cost of Philadelphia’s crumbling school infrastructure and fanned anxiety among educators, many wondering whether their own ailments trace back to something that lurked in their classrooms.

Unlike DiRusso, though, many of them will never conclusively know if working conditions caused their illnesses. That’s because mesothelioma is rare — both in its prevalence and in the definitive link it has to an environmental toxin.

Like DiRusso, Lynn Johnson worked for years in a building with a troubling environmental track record. And she, too, had to retire abruptly.

But in every other way, Johnson’s story is the photo negative of DiRusso’s.

Her illness is so mysterious, the medical establishment won’t even call it a disease. It has no known cause. It offers more questions than answers.

Johnson — and so many other teachers — will likely never know if any of this could have been prevented.

A dubious history

Johnson, now 60, was destined to teach.

The Harlem native grew up playing playing school with her identical twin sister, Leslie. Their mother taught science in New York City’s public schools. And even though the pair studied to become dentists, they both circled back to the classroom.

Lynn Johnson started as a substitute in the School District of Philadelphia in 1990. The career appealed to her because of its flexibility, allowing her time to raise her two daughters. But it quickly turned into a calling — an outlet for Johnson’s natural charisma and gregariousness.

“I became alive when I was in that classroom,” Johnson said.

In 1999, she moved to Franklin Learning Center, or FLC, a high school just north of Center City, and became a full-time biology teacher.

Johnson thrived there. She won the Lindback Distinguished Teaching Award, one of the district’s highest honors, and was a finalist for Philadelphia teacher of the year.

FLC has a proud history as a prize-winning school, but its four-story building, finished in 1909, has a more dubious past.

In 1996, students walked out of FLC because of suspected exposure to lead and asbestos. School district officials promised to demolish the structure and build a new one. They even put a price tag on the project: $30 million.

Talk of a new building lingered for years. Proposals went through modifications and tweaks and wholesale changes.

“I don’t remember a lot of the old-timers getting excited,” Johnson said. “I think that as you work with the School District of Philadelphia, you lose your trust in what they say they’re gonna do because sometimes it doesn’t happen.”

Indeed, the new building never happened. Instead, in 2010, the district set aside money to renovate FLC. It allotted about $3 million — one-tenth of the original budget for the new building.

Johnson recalls finding mysterious dust in her room when workers renovated the classroom above her. She said she remembers leaks and crumbling tile and an off-putting directive from administrators to never drink water from the school’s fountains.

When she heard the school was being renovated instead of destroyed, she felt more dread than relief.

“Something in my head went, ‘Oh, Lord, they disturbing up monsters,’” Johnson said.

Facilities issues surfaced again at FLC in December 2019, when the school district closed the school for several days after discovering damaged asbestos in an air shaft. The district has since reopened FLC, but parents and teachers staged a rally on the first day back to protest what they see as lingering hazards inside the building.

So far this school year, the district has closed six schools temporarily after discovering exposed asbestos. District officials say they’ve upgraded their protocols for finding and remediating asbestos, although the city’s teachers union has questioned the district’s efficacy in several instances.

When she was teaching there, Johnson knew her high school was old and in need of repairs.

That’s not uncommon. The district has itself admitted that it has billions of dollars in deferred maintenance — the legacy of old buildings and insufficient funds. Johnson figured that years in a century-old school might someday harm her, but it was never an acute concern.

“It’s in the back of your mind, wayyyyy in the back,” Johnson said.

‘I can’t hear’

Then in November 2015, those years of low-grade unease turned into blinking red warning lights.

After Johnson left her classroom that Wednesday before Thanksgiving, she spent much of the holiday weekend unable to lift her head from the pillow. That Sunday, she tried to attend church with her family, but midway through the service, she turned to her husband.

“I can’t stand,” she told him. “I can’t hear. Take me to urgent care.”

An urgent-care doctor suspected she had a bad cold and gave her Sudafed. But the symptoms didn’t subside.

Over the next six months, Johnson bounced from specialist to specialist. There was an infectious-disease specialist, a rheumatologist, and a pair of ear, nose and throat doctors. One by one, they crossed off potential ailments. It wasn’t a cold. It wasn’t Lyme disease. It wasn’t. It wasn’t. It wasn’t.

Meanwhile, Johnson spiraled. She resigned herself to the possibility of death.

She went totally deaf in her right ear, and lost partial hearing in her left. She lost the ability to balance without a cane. She gave up driving because her eyes seemed unable to focus whenever she turned her head.

“I’m stuck in this body where I can’t express myself. I can’t move. I can’t do anything,” Johnson said. “I fell apart.”

The mystery illness

In spring 2016, Johnson finally got a diagnosis of sorts: Cogan’s syndrome.

Cogan’s syndrome is so uncommon and ill-defined that it is not technically a disease. It’s a cluster of symptoms that the medical establishment has christened with a name because those symptoms surface in enough patients.

“It helps us so that we can group patients and think about how to treat them,” said Peter Merkel, an expert on Cogan’s syndrome and the chief of rheumatology at the University of Pennsylvania. “But it does tell us that perhaps we’re not as precise in our understanding.”

Patients with Cogan’s syndrome have an autoimmune disorder, meaning their own immune system is attacking healthy tissue. If that autoimmune response is taking place in a person’s inner-ear while also causing vertigo and eye inflammation, doctors may suspect Cogan’s syndrome.

There is no test that proves a patient has Cogan’s syndrome.

“A lot of it is patient symptoms, crude measurements, and our gestalt of what’s going on,” said Steven Eliades, assistant professor of otorhinolaryngology at the University of Pennsylvania. “[It] can be incredibly frustrating for the patient and, quite honestly, for me.”

The symptoms patients experience often subside — or at least stop progressing — in response to steroids. Through that treatment, along with physical therapy, people with Cogan’s syndrome can make modest recoveries. But the condition is chronic and has no cure.

With the help of special grip socks, Johnson can shuffle around her house in Delaware County. Longer walks require a cane or wheelchair, particularly when she’s out in public, on unfamiliar terrain.

Her hearing loss is permanent, making her a frustrated bystander in social settings where she used to thrive. Once the center of a room — her room — Johnson now needs other people to speak slowly, directly, and facing her so she can read their lips.

Johnson gravitated to science not because of what science tells us, but because of what it cannot tell us. She loved the notion that she could reach the limits of human explanation and stare out into the unknown.

“I think it connects me to my spiritual awareness,” said Johnson. “[Science] made me closer with God because there’s so much you don’t know.”

Now, the unknown greets her every day — in the form of an illness that the brightest medical minds struggle to understand. She struggled for years to reconcile her awe of life’s mysteries with the reality of what this mysterious ailment had done to her life.

“When this disease hit, bam, I questioned everything,” Johnson said.

A science teacher’s theory

It should be stated plainly: There is no scientific evidence linking Johnson’s illness with her work at Franklin Learning Center.

In fact, there is no accepted explanation for why anyone gets Cogan’s syndrome. It is a sickness without a known origin.

Johnson has long suspected, however, that her work environment somehow contributed to her illness.

When FLC was temporarily closed late last year, Johnson’s fears resurfaced.

She suspects a link between her school building and her illness for two main reasons.

The first is her history of allergies. Johnson had severe allergies as a child that required her to receive three shots a week, she said. Allergies are, at heart, an immune-system response to things in the environment that don’t typically trigger immune responses.

From this history of allergies, Johnson has concluded that her immune system is especially vulnerable to environmental triggers, and that she’s the type of person who might develop an immune-related disease after spending years in an old building with environmental hazards.

“My immune system was already on high alert,” said Johnson. “And it’s been on high alert for decades.”

The second reason for Johnson’s suspicions is genetic. She has an identical twin sister, Leslie Childs.

Childs does not have Cogan’s syndrome, nor does she display the same symptoms Johnson displays.

Childs lives in New York City and has never been inside FLC. The twins both believe that Childs’ lack of symptoms suggest that there is something in Johnson’s environment that unlocked her illness.

“It’s night and day between her and I physically now,” said Childs. “That’s the difference. Our environment was different.”

Dealing with uncertainty

None of this is conclusive.

The medical literature is far too thin on Cogan’s syndrome to make a judgment on Johnson’s suspicions.

Cogan’s expert Peter Merkel said he’s seen some evidence that people with the syndrome are more likely to suffer from chronic allergies. But he’s also seen some evidence that the illness may be brought on by a cold or infection. This is all from years of professional observation.

There’s no proof. For Johnson, there may never be proof of her theory — one way or the other.

“It’s difficult for patients. It’s difficult for physicians to deal with uncertainty,” Merkel said. “But that’s a lot of what we have.”

So why tell a story about a teacher who worked in an old school building and has a health condition with no known link to that school building?

In part, because so many stories about Philadelphia school teachers and illness will dead-end at this same point: We simply do not know.

We know that school buildings in Philadelphia have been poorly maintained. We know some teachers will eventually get sick. In individual cases, however, we often don’t know if the first and second things have any connection to each other.

What’s going on with my body?

Take the case of Sharon Newman Ehrlich.

The veteran science teacher worked for years at Edison High School in North Philadelphia, one of the district’s newer facilities.

In 2012, she transferred to Randolph Technical High School in the East Falls neighborhood. Almost immediately, she said, her lungs rebelled.

She developed acute breathing problems that made it almost impossible for her to last through the school day. A doctor eventually diagnosed her with “occupational asthma.” Ehrlich suspects something in the school triggered this response. She estimated she’s made 35 doctor visits over the last seven years to see if she can turn up more answers.

After wheezing through part of the 2012-13 school year, Ehrlich never taught again.

She eventually wandered down a paper trail to figure out if there was something about the building’s history that could explain her sudden reaction. What she found would alarm anybody.

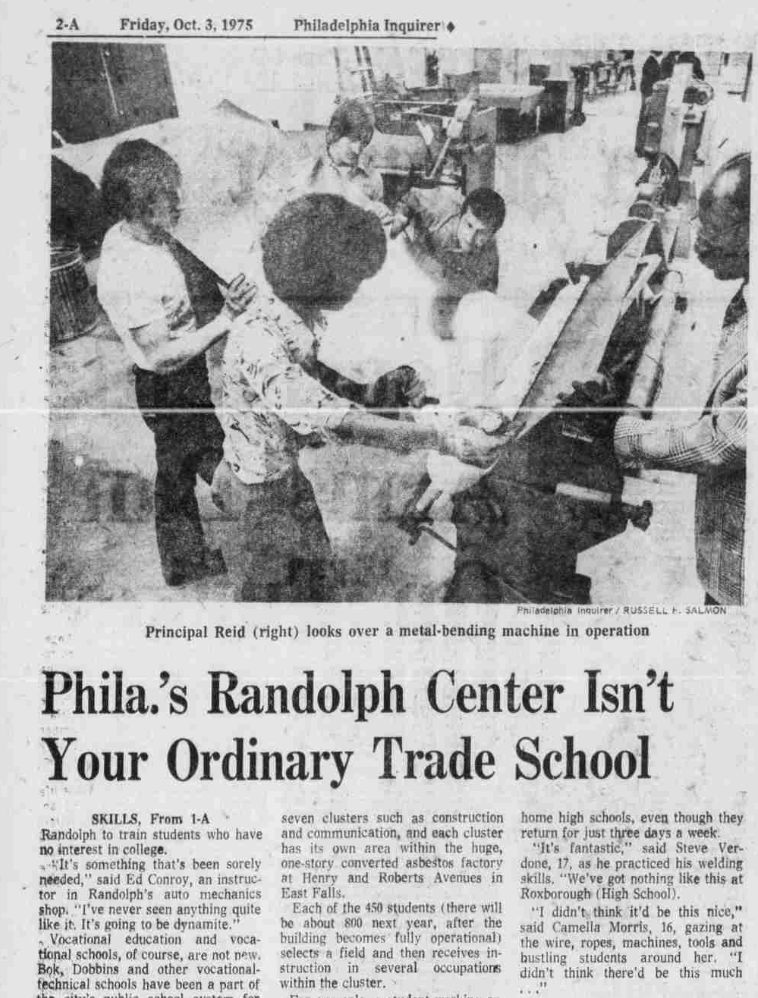

Randolph, it turns out, is located inside a renovated asbestos factory. That is not a typo. A current Philadelphia high school occupies the same site and structure as a converted asbestos factory.

The factory, run by a company called Asten-Hill Manufacturing, was sold in 1968. It opened as Randolph in 1975, just seven years later.

Could any of that explain Ehrlich’s health conditions? Again, it’s almost impossible to know.

“I just want to find out what’s going on with my body,” she said. “I want to live as long as I can, and I wanted to teach as long as I could. I loved it.”

Panic versus proof

Neither the teachers union nor the School District of Philadelphia could say how many city educators take early retirement due to medical conditions. And even if that number exists, it would take significant legwork to determine how many of those retirements had even a plausible connection to environmental toxins.

The union has repeatedly raised the specter of a teacher health crisis, drawing attention to DiRusso’s case and making allusions to “cancer clusters.”

But right now, there isn’t any widespread evidence that staffers in Philadelphia schools are more likely to develop serious illnesses than employees of other school districts.

There’s also the risk of over-attribution, of teachers — rightfully scared by media coverage of crumbling buildings — being too quick to draw a connection between their health and their schools.

Sometimes, public panic over illness and environment can have serious, real-world consequences. Several experts mentioned the perceived — and unproven — link between autism and vaccines as a cautionary tale. Though the medical establishment has found no tie between the two, parent suspicions have lingered for decades. And those suspicions are starting to depress vaccination rates in some places.

That’s not to say there’s no tie between old buildings and teacher illness — only that panic without medical proof can be a slippery slope.

Goodbye and thank you

After all this, Lynn Johnson is left mostly with questions and unresolved emotions.

Physically, she said, she’s improved — or at least adjusted. She uses FaceTime now to make calls so she can read lips. She’s more adept with her cane after going to physical therapy. And she volunteers with an organization that raises awareness about diseases similar to hers.

Still, she can’t teach. And it stings.

She loved the School District of Philadelphia. But after years of unfulfilled plans to move FLC and the onset of her illness, she no longer trusts the institution to watch after its own.

“How can you trust your employer? You can’t,” she said. “I don’t believe a word they say about all this.”

She’s not sure she has any legal recourse.

“I’m hearing you gotta get a lawyer,” she said. “[But] I’m going, ‘How do you prove something like that?’”

But Johnson still cherishes her time as a teacher. She uses words like “calling” and “gift” and “destiny.” How can you be bitter about doing the thing you were meant to do?

She’s grateful that she got to be a teacher in Philadelphia — even if she also thinks it ultimately sickened her.

Johnson only wishes it didn’t end so abruptly. She wishes she could at least walk back into Room 217 and gather up all the thermometers and test tubes she left on the tables on her final day. She wishes she’d gotten a retirement ceremony, or at least a call from someone acknowledging the end of her career.

“After all I put in — after suffering the illness, I still haven’t said goodbye … or thank you.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.