How 30 years of broken promises, false starts led to another Philly asbestos closure

Officials have known for decades about building woes at a Philly H.S. But despite protests and promises, not much has changed.

Franklin Learning Center. (The Flash/The Notebook)

Lynn Johnson began teaching at Philadelphia’s Franklin Learning Center in 1999 — and from the moment she stepped into the aging structure, she heard “constant talk” of a move.

The district had promised to relocate the high school after a 1996 student protest over poor building conditions. Johnson, an award-winning biology teacher, says she even sat on a planning committee to design new labs for the forthcoming building.

And then… crickets.

Promises turned into 16 years of inaction, and eventually, Johnson retired at age 55 when she developed a rare auto-immune disease that sapped her hearing and vision.

She can’t be sure if the ailment stems from environmental conditions inside her former school, but she wonders. And she wonders why — after decades of false starts and red flags — Franklin Learning Center still inhabits a building erected back in 1908.

“The school district isn’t surprised about the conditions at FLC,” said Johnson. “They knew about this for years, and just fell asleep.”

Last week, the school district temporarily closed FLC after discovering damaged asbestos in an air shaft. The building is now one of five in Philly that have been shuttered this year due to the toxic mineral. On Thursday, teachers from the school marched to district headquarters and delivered a letter alleging that their colleagues have developed myriad diseases due to poor building conditions that the district has “repeatedly ignored.”

And even former teachers like Johnson are speaking up.

“I loved working for the School District of Philadelphia. It was my calling. So it’s kind of hard for me to be angry,” said Johnson. “But at the same time, I can’t allow them to continue to put others at risk.”

The saga of FLC’s building spans more than a century — and in many ways, mirrors the journey of Philadelphia’s public school system: from growth-fueled overcrowding to ‘white flight’ to financial ruin to bureaucratic turmoil.

1908 — A building rises

At the turn of the 20th century, the School District of Philadelphia had a different kind of facilities problem: space.

The fast-growing city needed more suitable structures to educate its swelling population. At the start of the 1908-09 school year, nearly 20,000 children had to attend half-time because the city couldn’t build schools quick enough. And many students were stranded “in dilapidated structures, long since admitted as absolutely unfit for educational purposes,” according to a 1908 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

But there was a bright spot in the works: the William Penn High School for Girls, being built at 15th and Mt. Vernon Streets in Center City for $585,000.

The new school would distinguish itself by training young women in career paths like dressmaking, millinery, and library employment — an acknowledgment that modern women were working more and marrying later. The Inquirer called it “one of the most radical steps ever taken in this city in the interest and advancement of public education.”

But, from the get-go, the school experienced facilities issues. A planning delay pushed construction from the summer of 1908 to the fall, and postponed the opening of the new school by one year.

1973 — Farewell William Penn

In 1973, the school district shelled out roughly $14 million to move William Penn High School to a new campus at Broad and Girard Avenues in North Philadelphia.

The reason for the move was pretty simple, according to the Philadelphia Daily News:

“The school … was deemed too old a building,” said a 2012 article written about the era.

But the structure wasn’t sold or torn down. And, just one year later there was a new plan for the space.

1974 — Franklin Learning Center moves in

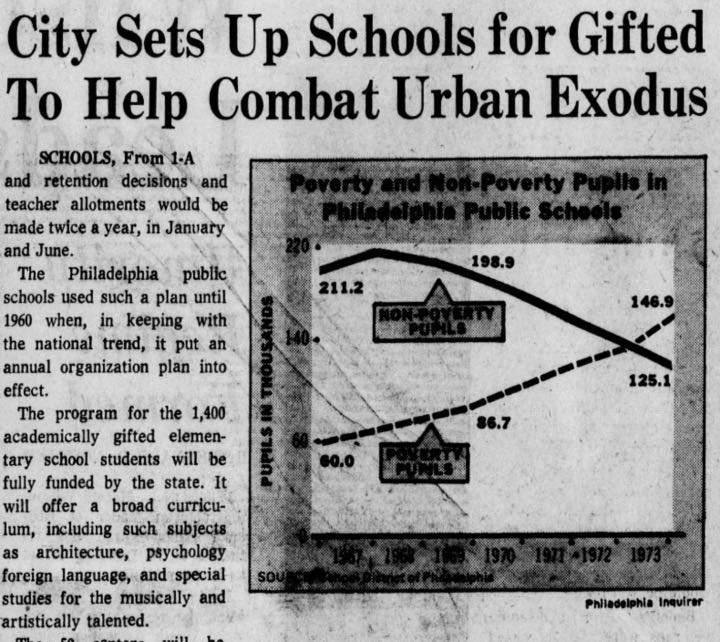

In 1974, Philly Superintendent Matthew Costanzo announced that, for the first time, more than half of Philadelphia’s public school population lived in poverty. To stop the exodus of middle-class families to the suburbs, the district announced a $1 million plan to create 50 “learning centers” located inside elementary schools around the city.

These new centers were essentially gifted programs. Students had to score in the 94th percentile or higher on a national achievement test to earn admission.

The district simultaneously announced the creation of Franklin Learning Center, a high school that would house programs for academic achievers, vocational education, and credit-recovery. Costanzo told the Inquirer that the plan to blend all of these programs in one school was a “bold, extremely innovative venture.”

1984 — The first asbestos scare

In March of 1984, the Environmental Protection Agency slapped the School District of Philadelphia with a $12,000 fine for failing to properly post warnings about asbestos in two city schools: Julia R. Masterman and FLC.

New federal regulations required the district to post notices in the teacher’s lounge of every school where the newly banned material had been used. The district contested the fines and brushed aside any concern.

“They found some fine print in the federal regulations and hit us with it,” district spokesperson J. William Jones told the Philadelphia Daily News.

District officials said that when it came to asbestos issues writ large, they were ahead of the curve. They boasted of a $17.7 million plan to take asbestos out of 290 schools over the next three years.

1990 — FLC flirts with its first move

By 1990, the city’s shrinking tax base and the district’s resultant financial woes were taking their toll on Philly schools.

In a Philadelphia Daily News story titled “Budget Woes Put Damper on School Repairs,” reporters chronicled leaking roofs, balky heating systems, and a decision to defer $4 million in asbestos removal.

Deputy superintendent J. William Jones confessed to the paper that the district — which hadn’t established a capital building budget until the mid-1980s — was paying for decades of neglect.

Franklin Learning Center needed $6 million in repairs, but district officials considered that too pricey. Instead, they pushed a plan to buy the recently shuttered West Philadelphia Catholic School for Boys at 49th and Chestnut Streets at $4.5 million dollars.

The current location at 15th and Mt. Vernon Streets was “in serious disrepair, with a leaky roof, broken windows, crumbling walls and faulty heating,” according to a May 29th story in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

1991 — But parents say no

Community opposition quickly scuttled the proposed move to West Philly.

Some said FLC couldn’t serve its far-flung student population if it left Center City. Others objected to the new location because they deemed the neighborhood too dangerous.

That swath of West Philadelphia had been hit hard by the same forces that were crippling district finances: suburbanization and urban disinvestment.

Parents and students weren’t keen on the West Philadelphia plan.

“It doesn’t matter what race or color you are, the harsh reality is that it is unsafe to go into some of this city’s neighborhoods if you are an outsider,” said Mitchel Little, a Franklin student, in one Inquirer article.

Folding to pressure, Superintendent Constance Clayton opted to keep FLC at its old location and spend $3 million on renovations to the roof, piping, and plaster.

1996 (March) — The students strike back

Those renovations did not satisfy students and staff. And on March 25, 1996, they made it known.

About 150 FLC students stormed the old school district headquarters on Benjamin Franklin Parkway and blocked traffic on the busy thoroughfare. Worried about lead and asbestos exposure in their 88-year-old building, the students demanded an audience with Superintendent David Hornbeck.

Hornbeck eventually came out to speak with the crowd, assuring them the district had conducted a thorough review of the building and that there was no health risk. Those gathered weren’t buying it, according to the Daily News:

“He’s a liar,” shouted Agnes Dumas, who described herself as someone concerned about the children. “We need to get these chumps out and get an elected school board.”

That same day, Hornbeck announced dramatic budget cuts that would force officials to slash after school clubs and scale back plans for full-day kindergarten — a plan that still left the district with a $43 million deficit.

1996 (April) — The big promise

In mid-April, the school board yielded to community pressure and said it would spend $30 million to tear down FLC and build a new facility in its place.

School board president Andrew Farnese said FLC students would be relocated to temporary facility in January of 1997 and that construction would take three years.

Neither of those things ever happened.

1998 — A plan emerges

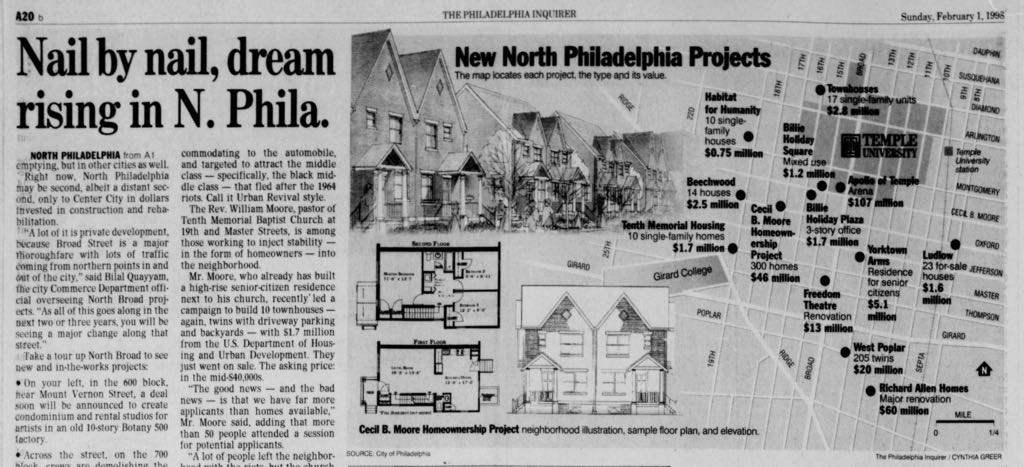

The district instead pivoted toward a new plan: building a new school on an abandoned lot about a half-mile north of the current location.

The land under the then-recently-demolished City Cadillac Building at the corner of Ridge Avenue and Broad Streets was supposed to be FLC’s home, but the plan fizzled amid bureaucratic turmoil.

In 2001, in response to Hornbeck’s threat to stop having classes unless the state greatly increased aid for city schools, the state disbanded the local school board. It installed the five-member School Reform Commission in an attempt to turn around the failing school district.

Somewhere in that transition, the district’s commitment to its FLC plan vanished.

A current school district spokesperson told WHYY that a combination of new leadership and fiscal miscalculation led to the shift.

“Once design development began, the price for the project exceeded the budget and the project was put on hold,” wrote spokesperson Imahni Moise in an e-mail. “In 2002, there was a change in administration (Paul Vallas became Superintendent) which led to a change in capital program initiatives, so instead of being torn down and rebuilt, FLC went under major renovation.”

2010-2012 — Another renovation

In 2010, the district set aside $2.9 million to renovate the FLC building, which had recently celebrated its 100th birthday.

Roughly 40 years after William Penn High School moved out — and 30 years after district officials first tried to relocate FLC — the district embarked on another patch-up campaign.

In 2012, according to the Daily News, officials floated another plan to relocate FLC to the abandoned lot at Broad and Ridge Streets — which abuts the historic Divine Lorraine Hotel.

This idea by developer Eric Blumenfield would have created a new campus on the space to house four public schools: FLC, Julia R. Masterman, Parkway Center City and Benjamin Franklin High School. District officials told a reporter they’d had some “exciting” preliminary conversations with Blumenfield, but there’s little evidence that those conversations went much further.

Eventually, Blumenfield converted the Divine Lorraine into an apartment building and rehabilitated the nearby concert venue, The Met. The property intended for the schools was purchased in January 2019 by Broad Street Development LLC for roughly $4 million, according to city records.

2019 — Asbestos redux

Now comes the latest twist in a building saga that dates 111 years.

Last week, officials discovered damaged asbestos and decided to close the building temporarily. They say students will be able to return on January 2nd after winter break ends.

The school district recently set aside $12 million to accelerate asbestos abatement and pledged to respond faster when workers report toxic threats.

“To our parents, I want to say, I hear you,” said Superintendent William Hite. “I understand your concerns. I am committed to getting this right.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.