Zimmerli Art Museum in New Brunswick presents Odessa’s Second Avant-Garde

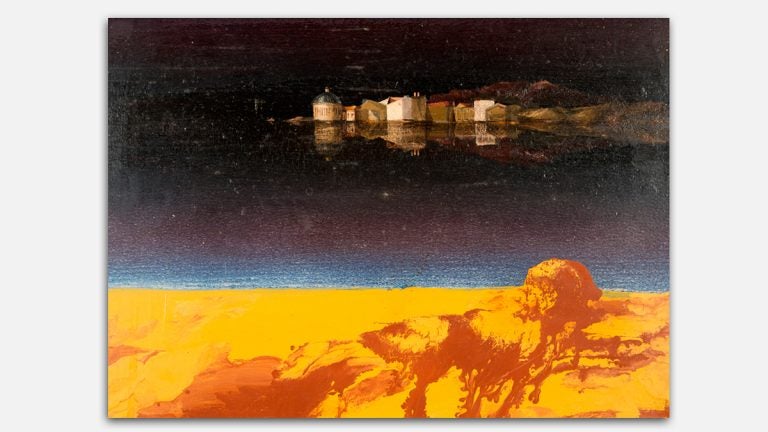

Reflection of the City, 1978 by Lucien DulfanOil on cardboardCollection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers

Odessa’s Second Avant-Garde: City and Myth, on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum through April 19, showcases artists most of us have never seen before, nor can we pronounce their names. Theirs is an artwork that opens our eyes to a new world.

And yet there is something familiar in what they were doing. Despite the differences between American and Soviet cultures, artists were expressing themselves with collage and abstraction, in conceptual ideas and playful ways, inventing theories about the world and merging the mundane with the divine.

Odessa — the third largest city in Ukraine, located along the Black Sea – has been a melting pot since it was founded by a decree of a Russian empress in 1794. Built on an ancient Greek settlement, its plan was laid out by a Dutch engineer. The Mediterranean and neo-Baroque architecture has Italian influence, and the first two mayors were of French descent. A large Jewish population was deported to concentration camps during World War II. Eastern Europeans from former Soviet Bloc countries make up today’s residents.

Odessa has not been immune to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. There have been protests, bomb blasts, and numerous deaths as a result of the unrest. But during the time period explored in this exhibition – the early 1960s through the late 1980s – the fabled seaport city offered artists and writers inspiration.

“Together with St. Petersburg and Moscow, Odessa is among the most mythologized cities in Russian literature… prompting artistic reveries about a past golden age and its possible return,” notes the exhibition catalog. Russian language journalist, playwright, literary translator, and short story writer Isaac Babel found that Odessa’s warm sunny climate, linguistic diversity and democratizing impulses “was everything St. Petersburg was not: an elusive but beautiful dream to which the foggy and mysterious Russian capital could never compare.”

Curator Olena Martynyuk, a Dodge Fellow at the Zimmerli and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Art History at Rutgers, grew up in Ukraine, spending her first 16 years in the region surrounding Odessa, then moved to Kiev to study philosophy, history and art. She came to the U.S. under a Fulbright Fellowship and began her doctoral work in 2009, with a concentration in Ukrainian and Russian nonconformist art — her dissertation examines Ukrainian and Russian art made in Moscow during and after Perestroika.

The Zimmerli has the largest collection of Soviet nonconformist art in the world, thanks to a 1991 donation from Norton and Nancy Dodge. Artwork in all media, from painting and photography to assemblage, video, installations and artists’ books, reveal a culture that defied the politically imposed conventions of Socialist Realism. The work comes from the period 1956 to 1986, and includes art produced in the Soviet republics.

Norton Dodge (1927-2011) is credited with singlehandedly saving contemporary Russian art from total oblivion. An American economist, Dodge traveled to the Soviet Union in the 1950s, studying the role of women under the Stalin regime. He became interested in dissident art, meeting clandestinely with artists and building a collection. “He was invited to unofficial openings. Artists were not allowed to exhibit in public places,” says Martynyuk. “These were homelike settings. There would be KGB members there, taking information.”

During the Cold War, Dodge smuggled 10,000 works of art to the U.S. John McPhee wrote about Dodge in “The Ransom of Russian Art” in 1994.

Martynyuk had the opportunity to get to know Dodge before his death. In 2011, she traveled to the Odessa Museum of Modern Art to give a talk about the Dodge Collection. “Many of the artists, now in their 70s, came to hear the talk,” Martynyuk recounts. “They shared their experiences with students, telling them how they weren’t sure if their artwork would be interesting to anyone else. It was so important to them to have a collector who cares about their work and considers it important. Previously they had no audience for their artwork. The Odessan artists bought a bottle of cognac for Norton Dodge as a token of their appreciation.”

During the late 1950s and early 1960s – in the post-Stalinist, more liberal era known as Khrushchev’s Thaw – many artists from Odessa began to challenge the Socialist Realism that had dominated Soviet art institutions since 1932. Artists were inspired by the saturated colors and Mediterranean ambience, harking back to the city’s origins as an ancient Greek settlement. They also drew inspiration from the early 20th-century achievements of the radically innovative Russian avant-garde traditions. Others turned to abstraction and Conceptualism.

“In contrast to the harsh social and political circumstances throughout the Soviet Union at the time, the sunny climate of Odessa became – and continues to be – a metaphor for autonomy and possibility,” says Martynyuk.

Far from the big city — Kiev and Moscow – apartment exhibitions developed in the 1970s as underground galleries for sharing new work. Gallery-goers enjoyed this “deviant” art alongside prohibited jazz records and western art books, resurrecting the subversive atmosphere of the Odessa café-cabaret, which had flourished at the turn of the 20th century.

These Odessan artists, who held day jobs to support themselves, formed a tightly knit artistic community, though there was no style or ideology that united them.

In the summer of 1967, when no alternative exhibition spaces existed, two young artists decided to stage an exhibition themselves — on the fence surrounding Odessa’s famous Opera Theater, which was undergoing reconstruction. Stanislav Sychev and Valentin Khrushch created their own independent exhibition on one of the most crowded streets in Odessa, ensuring that many people would see their art. The Fence exhibition was the first nonconformist art event held in a public space in the Soviet Union.

“This community was thriving,” says Martynyuk. “They didn’t let censorship stop them from voicing their message. Now we can show what was verboten. I wanted to show how strong this art is, how audacious.”

Odessa’s Second Avant-Garde: City and Myth is on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University through April 19.

_________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.