Historical Society spotlights a century of Philly public art by women

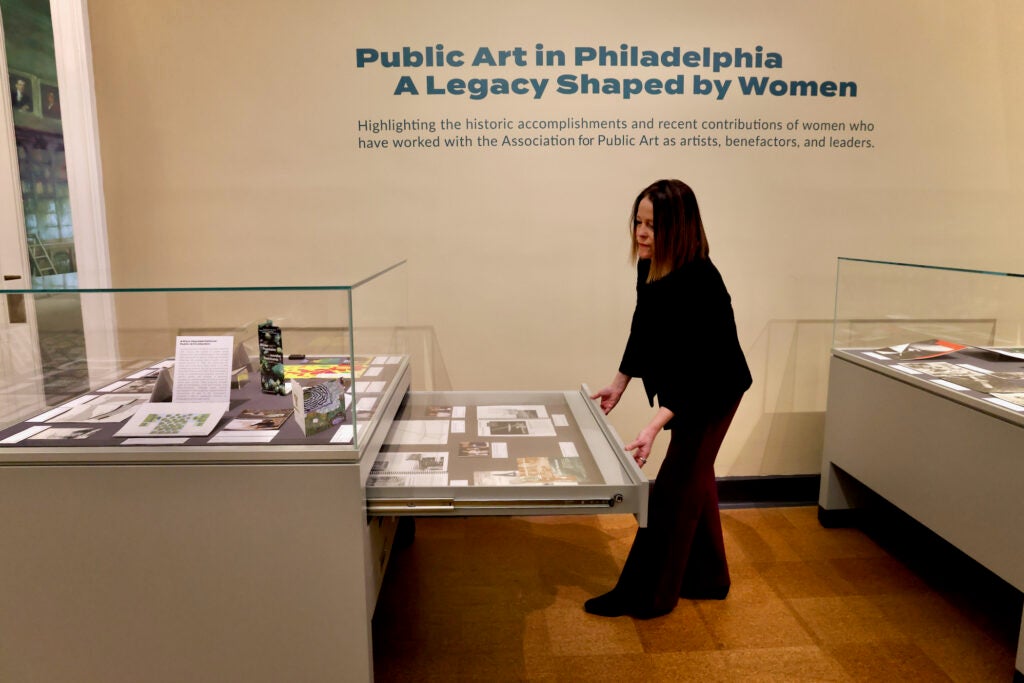

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania partnered with the Association for Public Art for their exhibit, "Public Art in Philadelphia: A Legacy Shaped by Women."

Staff members from the Historical Society of Philadelphia and the Association for Public Art check out a new exhibit showcasing the role of women in public art. ''Public Art in Philadelphia: A Legacy Shaped by Women'' is the first exhibit in a series of collaborations by the Historical Society in celebration of the organization's 200th anniversary. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Where have all the fish gone?

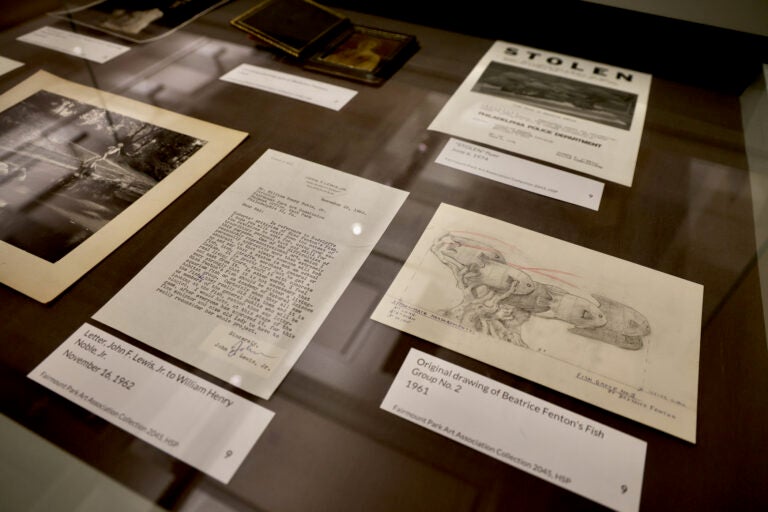

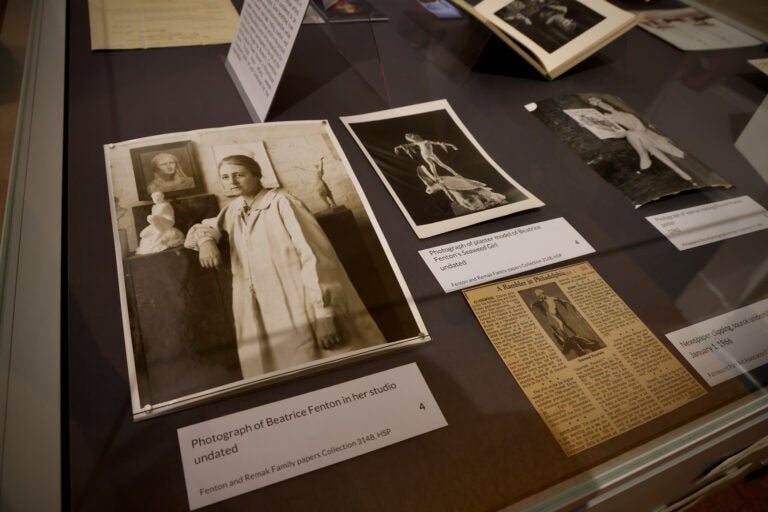

In 1961, the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) commissioned artist Beatrice Fenton to make two bronze sculptures of a schools of angel fish. They would accompany her previous sculpture, “Seaweed Girl Fountain,” installed 40 years earlier at the former Lemon Hill pond.

The fish got some pushback.

An entomologist at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Radclyffe Roberts, complained that Fenton’s fish were not sufficiently accurate to the anatomy of actual angel fish. So the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts board president, John F. Lewis, Jr., reached out to a colleague, William Henry Noble, and asked him to smooth things over with the prickly taxonomist.

“One of the difficulties of reasonably representational art…is that always someone would bob up and say that a statue is not an actual fish, lion, giraffe, general, or Indian,” Lewis wrote in a letter to Noble. “I would hate, at this stage of the game…for this fine sculptor and nice old lady to have to really reconsider the project.”

With ruffled feathers (or, scales?) smoothed, Fenton’s fish were cast and installed on either side of “Seaweed Girl” for a decade.

Then, one night in 1974, they were stolen. Both 500lb bronze fish sculptures were cut out of their mounts. Police released fliers asking for help recovering them.

The fish were never seen again, suspected of having been melted down for the value of the metal. Fearing the girl would get it next, “Seaweed Girl Fountain” was moved inside the greenhouse of the Fairmount Park Horticultural Center, where it resides to this day. Ultimately, the Lemon Hill pond would be filled in.

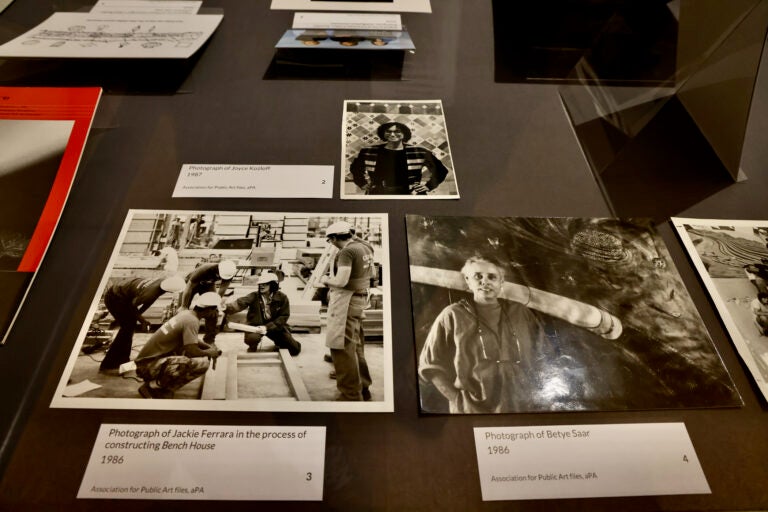

The letter, a preliminary sketch, a photo of the fish happily swimming next to their girl, and the “Stolen” flier tell this fish story in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s exhibition, “Public Art in Philadelphia: A Legacy Shaped by Women.”

The Historical Society houses the first century of archives, from 1872 to 1976, of the Association for Public Art (aPA), the country’s oldest public art non-profit. To mark HSP’s 200th anniversary, it will host five exhibitions by five local non-profits whose archives are held at the library. “Public Art in Philadelphia” kicks off the year-long celebration.

“It’s a really important history, and it’s a living history,” said HSP director David Brigham. “The organization is still very vital and creating work and thinking about the future. One of our larger messages is how the past informs the future.”

The new executive director of aPA, Charlotte Cohen, began just five months ago, having had much experience with public art in New York City but little in Philadelphia. The exhibit has given her a crash course in her new hometown.

“It’s a crash course for me in the history of Philadelphia and for the development of the city, particularly,” Cohen said. “[aPA] started in 1872 before the Parkway existed, before the anchor cultural organizations existed, and it’s always been very involved with urban development and urban design issues. That, to me, is really fascinating.”

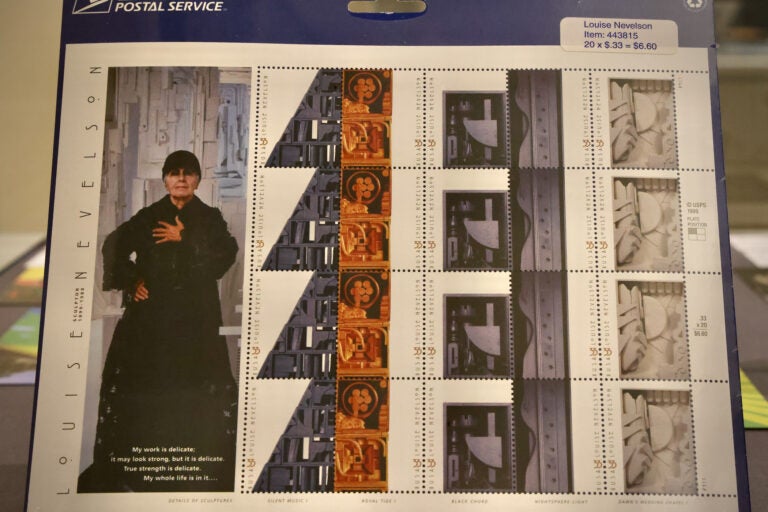

“Public Art in Philadelphia” curator Susan Myers has had a longer history with the Association for Public Art, having worked there for 20 years. She wanted to put together a display with “forgotten gems and untold stories,” concurrent with the city-wide exhibitions of women and non-binary artists in Philadelphia, “(re)Focus 2024.”

“One of the things I’m learning as I’m digging through all of the history is, it was not typical for women to be recognized as professional artists. That was an unusual path to take,” Myers said. “Maybe not so much in the 1940s, but earlier on that was an unconventional lifestyle choice for women.”

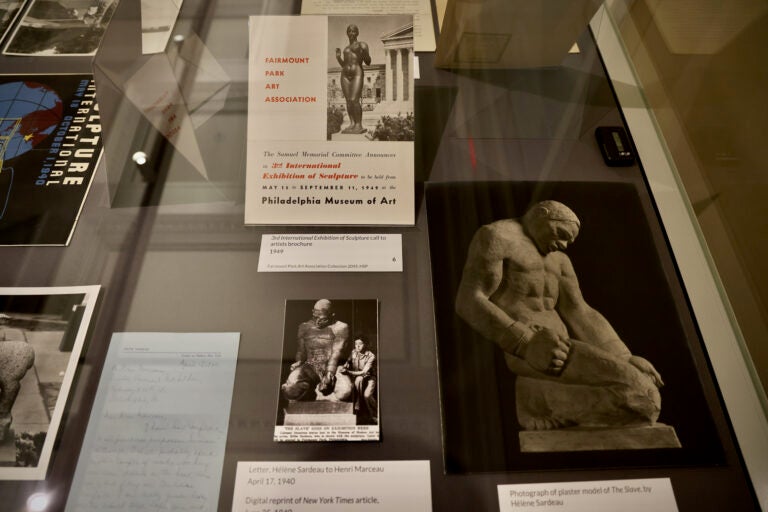

Myers dug into the first three international expositions aPA put on, a series of important shows that drew hundreds of submissions from sculptors around the world.

The exhibitions were spurred by the largest single donation aPA ever received: about $800,000 ($24 million in today’s dollars) from Ellen Phillips Samuel upon her death in 1913. The Association used the three Internationals to inform the development of the Ellen Phillips Samuel Sculpture Garden, which still lies along the Schuylkill River, just below Laurel Hill Cemetery.

“The crazy thing about that was the amount of women that were in those three exhibitions,” Myers said. “There were about 80 women represented across the three, which is pretty surprising. They were women artists who worked in sculpture, which was even less of a thing than working in painting or drawing or illustration.”

The exhibition cases include flat file drawers that visitors can pull out to see more material, including details about Sylvia Judson Shaw’s “Lambs,” a pair of lambs carved in granite now housed at the Horticultural Center, and Hélène Sardeau’s “The Slave,” the only sculpture by a woman included in the final Samuels Sculpture Garden.

Myers also stumbled on women she had never heard of: Gwen Lux submitted work to one of aPA’s International shows, but it was not acquired. Lux came to fame early in her career for an art deco sculpture, “Eve,” at Radio City Music Hall. It was initially rejected by impresario Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel for his private VIP suite but ultimately included in Radio City’s 50th Street foye..

Lux also designed the first-class dining room of the SS United States, the famed cruise liner that has long been moored in the Delaware River in South Philadelphia, now stripped, empty, and awaiting its fate.

The final element of “Public Art in Philadelphia” is still forthcoming: a series of street pole banners designed by Xenobia Bailey, a textile artist who has shown widely, including on the TV show “The Cosby Show” and the Spike Lee movie “Do the Right Thing.”

Originally from Seattle, Bailey has resided in Philadelphia for the last eight years, according to Cohen, but has never shown her work in the city. Her banner design will be inspired by holdings in the HSP archive related to historically elite Black families who were both financially successful and socially radical, such as the James Forten family.

“Some people were very entrepreneurial, forming abolitionist societies and schools and businesses,” said Cohen. “She’s really concerned about the image of Black people being positive, being these exemplary, amazing people.”

Bailey’s banners are expected to be installed by March 8 on street poles in the West Washington Square neighborhood around the Historical Society. She will also deliver a lecture at HSP on March 13.

“Public Art in Philadelphia: A Legacy Shaped by Women” will be on view until March 15.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.