Why spot zoning is probably here to stay

When Comcast unveiled its plans for a new skyscraper earlier this year, Council President Darrell Clarke introduced a few bills adjusting the zoning rules for the parcel in question so that Comcast wouldn’t have to go to the zoning board.

When Drexel University was in the process of buying University City High School from the School District, Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell introduced a bill up-zoning the property to fit Drexel’s still-vague development plans.

Just last month, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson introduced a few bills rezoning properties for the redevelopment of the Royal Theater and the construction of a new hotel in place of Little Pete’s, a diner in Center City.

All of these cases involved the remapping of an individual property, a practice which is sometimes called—usually pejoratively—spot zoning.

Spot zoning is an imprecise term, and it’s generally used to refer to any action that changes the rules of a zoning code in response to a particular development proposal. When it’s done sloppily, it can be considered illegal. Yet in Philadelphia, some form of zoning by ordinance, rather than through the zoning board, occurs regularly.

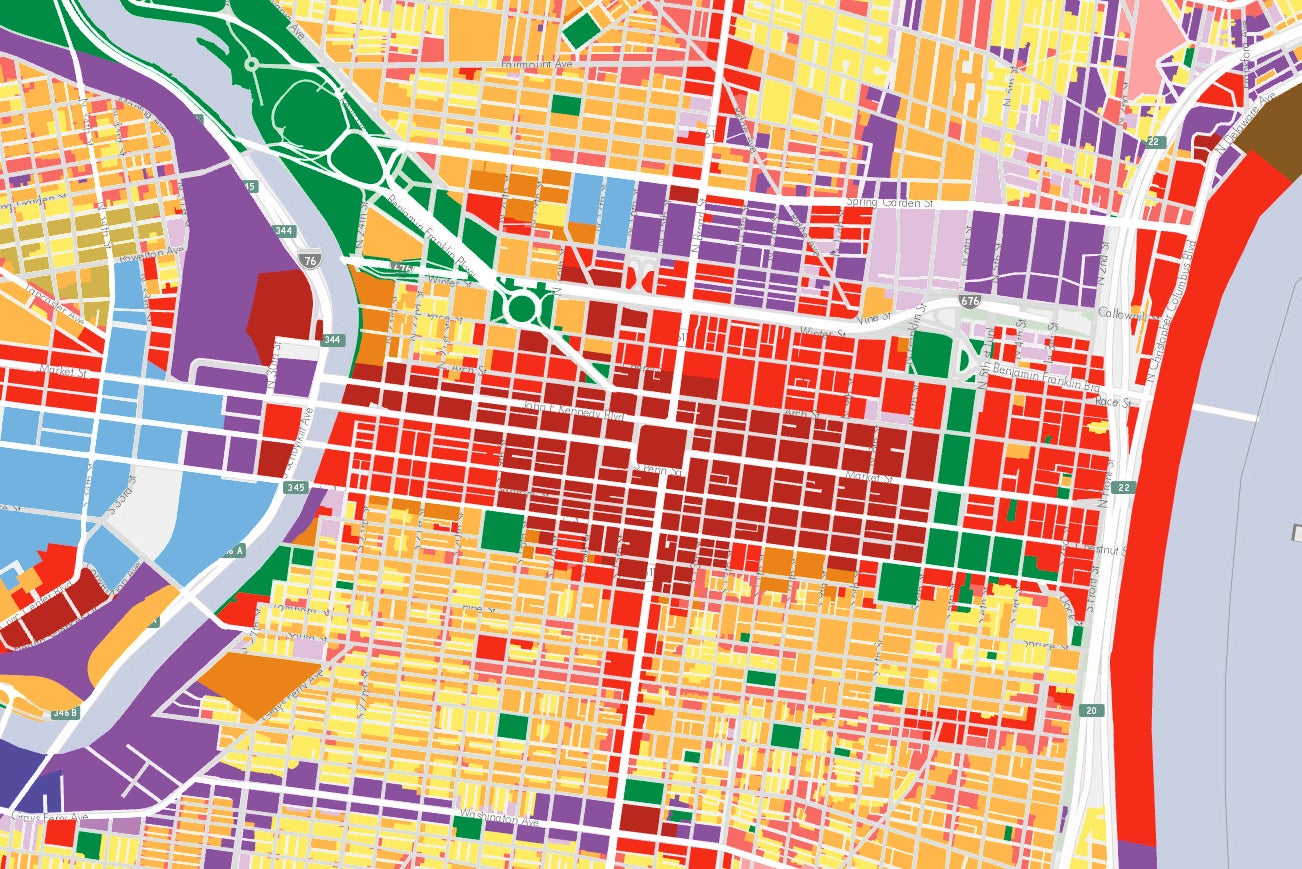

From a planning standpoint, spot zoning or zoning by ordinance is problematic because it focuses on individual properties rather than broad, forward-looking community plans. At the same time, in a city with so many outdated zoning maps and a comprehensive planning process that’s underway but slow-moving, proposals pop up that don’t conform to the zoning code and aren’t likely to be approved by the zoning board.

Some of them are even good projects, some argue.

“In a perfect world we would have the city properly mapped and it would be continually updated as its needs changed,” said Paul Boni, a land use attorney who has been outspoken about spot zoning in the past.

Boni acknowledged that rezoning a particular property by ordinance rather than through the zoning board is sometimes innocuous, but he said that the more the city updates the maps on a property-by-property basis, the less incentive there is to do a more comprehensive remapping.

Courts have ruled certain actions to be illegal spot zoning, but those cases usually involve a challenge by the owner of the property in question, according to Andy Ross, a city solicitor who works on zoning issues.

“The kind that seems to more traditionally get into trouble with the courts is when the dispute is between the government and the owner of that property,” Ross said.

Ross said the important thing is that there is a justification to rezone a particular parcel, and that a bill doesn’t single out one property to be changed to a use category that’s wildly out of step with the surrounding parcels. When the owner of the property supports the change, it’s less likely there will be a successful legal challenge, he said.

“It’s legal when we do it for a good reason,” Ross said, half-joking. “Otherwise it’s not.”

In 2007, before the Zoning Code Commission was created to rewrite the city’s fifty-year-old code, Harris Steinberg, the former director of PennPraxis, wrote an op-ed in the Inquirer saying that one of the reasons reform was needed was to reduce the incidence of spot zoning.

“Spot zoning is neither sound policy nor practice,” Steinberg wrote. “It keeps the development world in a constant state of guessing, encourages backroom deals, and keeps community groups on the defensive to protect their little piece of earth.”

The practice also raises suspicions about pay-to-play. After Councilman Johnson introduced the rezoning bills for the Royal Theater and the new Hudson Hotel, Ori Feibush, a Point Breeze developer who is challenging Johnson for the 2nd District Council seat, released a statement criticizing Johnson for accepting campaign contributions from people with interests in those properties. Johnson received more than $5,000 from Stephen Pouppirt, the lead developer of the Hudson Hotel. He has also received contributions from Kenny Gamble and his wife, who own the Royal Theater, and from Carl Dranoff, who is leading its redevelopment.

Last year, City Council adopted an amendment to the zoning code creating an overlay for the “approach” to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. The overlay was inspired by the proposed apartment complex at 205 Race Street, which didn’t comply with the zoning code. Greg Hill, one of the developers of 205 Race, gave campaign contributions to Councilman Mark Squilla, who introduced the bill, as well as to his predecessor, Frank DiCicco.

Peter Kelsen, a zoning attorney who has represented both Carl Dranoff and Drexel University, said that while it’s impossible to quash those suspicions, there is no pay to play happening in Philadelphia’s City Council.

“I really will tell you that there is not this culture that if you want to have legislation introduced by Mr. or Mrs. X Councilwoman, you need to give a contribution,” Kelsen said.

“The folks we have in City Council currently are a very credible bunch,” he added.

Kelsen said that he encourages his clients to pursue legislative rezoning rather than a variance when the zoning of the property is obviously wrong, as in the case of University City High School, a massive, former school property on a major corridor which was zoned for residential use. He also encourages legislative rezoning when an area is being looked at by the Planning Commission for remapping, but the new map won’t be introduced early enough to fit the timeline of a development project.

Until the Planning Commission is finished remapping all the districts, and all of the necessary bills are introduced and adopted by City Council, single-property rezoning is likely to continue. In reality, spot zoning is likely to continue long after the whole city has been remapped. In the meantime, some neighborhood groups are developing policies to guide their support or opposition to rezoning bills.

The Center City Residents Association is working on a policy which holds that developers should always seek zoning relief through the Zoning Board of Adjustment rather than City Council, except in “extraordinary circumstances.” The South of South Neighborhood Association is developing a process of community input on rezoning bills that mimics the meeting protocol required when projects go to the zoning board. As it stands, communities can weigh in on remapping actions during Council Committee hearings, but the zoning board process requires meetings between community groups and developers to talk about the specifics of a proposal.

“In a city where developers always want more, more, more, it might be the case that spot zoning continues unabated …” said Paul Boni.

“I just look at it as though land use laws should come from professional land-use planners, city planners,” he added. “It should come from the Planning Commission and should come in a comprehensive manner so that they’re looking at a neighborhood and not one particular property.”

This article also appears on This Old City

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.