Why so few of Philly’s homeless Latinos use shelters, get city services

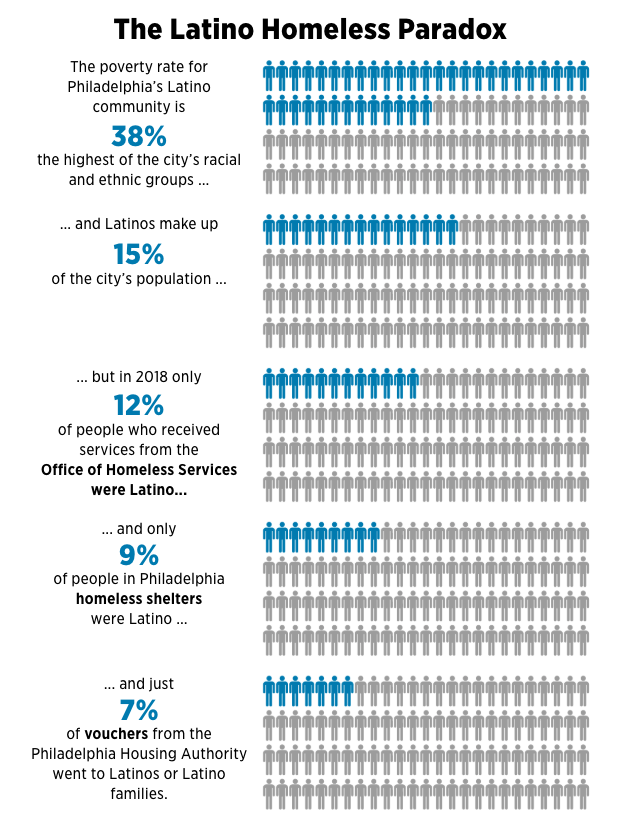

Latinos make up nearly 15% of Philly's population and form its poorest minority group — 38 percent live in poverty, according to census data.

Eduardo Aponte shares a room with other homeless men in Kensington or sleeps on the street most nights. He's one of many Latinos who avoids homeless shelters, who the city is trying to reach. (Emma Restrepo/Philadelphia Inquirer)

This story originally appeared on Philly.com

—

Edgardo Aponte sleeps most nights in the parking lot of a Kensington Save-A-Lot. When he has money, he’ll share a room with as many as five other men in a nearby rowhouse. He’s been homeless for several years and like most of the people who share the supermarket lot, he’s Latino, originally from Puerto Rico.

Linda Morales Bryant has moved with her husband and three children three times in the last year. She’s gone from her mother’s house to a friend’s house to a friend of a friend’s. When things got really dire this fall, the family considered pitching a tent somewhere to avoid getting split up in the city’s shelter system.

They represent two faces of Latino homelessness in the city, an underserved, undercounted group that advocates say isn’t reaching city services designed to help them.

Latinos make up nearly 15 percent of Philadelphia’s population and form its poorest minority group — 38 percent live in poverty, according to census data. But step inside a city homeless shelter and there are few Latinos. Nationally, and in Philadelphia, they represent a small fraction of people in shelters.

It’s been dubbed the Latino Homeless Paradox. Wary of shelters, Latinos are more likely to live on the streets or couch-surf among friends and family.

(John Duchneskie/Philadelphia Inquirer)

Advocates say many Latinos don’t go to shelters because of language barriers and because the available beds are not near their neighborhoods. Culturally, there is also a tendency for families to cram together before letting members go to shelters. But since most city housing programs are accessed through shelters, profound need goes untended.

“I don’t want to pit one poor community against another or one sad story against another,” said Will Gonzalez, who heads Ceiba, a coalition of Latino community-based organizations, “but the fact is the community that has the highest rate of poverty in the city of Philadelphia is, proportionally speaking, being inherently discriminated against.”

Undercounted?

The city’s January 2018 homeless survey found 4,705 people living in shelters, only 411 of whom were Latinos. (Latino generally refers to anyone of Latin American origin, whereas Hispanic refers only to persons of Spanish-speaking ancestry.)

Sister Mary Scullion of Project HOME said the Latino population “is definitely underrepresented” in established shelters, although some do reach out to Latinos. “Are there enough? No. Do Latinos come to the bigger shelters where most people access services? No.”

Of 980 people counted living on the streets last year in Philadelphia, 103 were Latinos. On the whole, despite Philadelphia’s high poverty rate, it has fewer people sleeping on the streetsthan most other big cities.

“The most simplistic way of saying it is that Hispanics don’t go to shelters,” Gonzalez said. “In our culture and I’ll talk about Puerto Rican culture, it’s this idea of hijos de crianza, the children that are ours based on raising them. We don’t let people sleep out. You stay in my basement. You stay in my couch. I may get pissed off at you in six weeks, but you’ll go to another couch, you’ll go to another basement.”

Here, the Latino population is 58 percent Puerto Rican and in general, those are the Spanish-speakers receiving housing services, advocates say, including hundreds who escaped devastation in Hurricane Maria. Latinos who aren’t from Puerto Rico seek out shelter or public assistance even less often, in some cases because they are undocumented. Dinorah Diaz, manager of housing services at Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha (APM), said that in the 20 years she’s worked in homeless services in North Philadelphia, she’s helped only two Latinos who weren’t Puerto Rican.

Latinos in Philadelphia are missing out on help from the city: Of the 16,549 people assisted last year by the Office of Homeless Services, just 1,362 were Latinos.

The disparity is apparent in public housing, too. The Philadelphia Housing Authority’s housing choice voucher program, formerly known as Section 8, is just 7 percent Latino families.

“The Latino community historically has not applied for PHA housing at a rate matching its percentage of the city’s population,” spokesperson Kirk Dorn said. “This is despite PHA’s marketing efforts to the Spanish-speaking community.” Since 2014, PHA has launched four housing projects in Latino communities.

The city says it continues to look into opening a shelter in a heavily Latino community and has pledged to amp up outreach efforts, but with limited beds, resources have to be distributed through a centralized intake process that favors people with the most need.

“It’s the saddest, most painful part of running a system where you can’t help everybody,” said Liz Hersh, the city’s director of homeless services. “But it really is a life-and-death kind of thing. [We help] people who are very seriously ill, who are much more vulnerable. That’s really what we’re looking at. It’s horrible to have to make these choices.”

Barriers to shelter

To get into the city’s homeless housing system, a person must be interviewed at one of six central intake centers. Most are in Center City. None are in North Philadelphia’s predominantly Latino neighborhoods. Travel alone can be a deterrent.

Aponte, who is living on the streets of Kensington and struggling with mental illness, said he’s mostly avoided shelters because the few times he went he paid for transportation only to find out they were full.

There is a perception among some Latinos that the city’s shelters aren’t for them. “They see that I do not speak English, they do not accept me,” said a man named Angel, sitting on the sidewalk at Second and Allegheny, who declined to give his full name.

Carlos Goytia has been homeless since he came to Pennsylvania from Puerto Rico in 2009. He moved among churches, rooming homes, and some shelters, struggling with addiction. Now 40 and one year sober, he said the rooming homes he once shared with addicts and drug dealers aren’t an option if he wants to stay clean. He’s working with Diaz at APM to find more permanent housing. A counselor there has encouraged him to go to the city’s shelters and stay put. Typically a person can’t get on a wait list for housing unless they have been in shelter for at least a week, Diaz said.

“You go there and no one there speaks Spanish,” he said. “You’re sort of isolated, on your own. You complain about unfair treatment and you’re insulated. ”

Out of 181 staffers, the city’s Office of Homeless Services has 12 people who speak Spanish, Hersh said. If a Spanish-speaker comes into a shelter and no one on staff speaks the language, the employee is expected to call a telephone translation service. The office also has a hotline available to anyone who feels they’ve been mistreated.

Catherine Robles, 28, stayed in a family shelter with her three toddlers, ages 4, 3, and 2 years old, for a year and a half, waiting for a housing voucher to come through. She said she was one of the only Latinas there. “The whole time there were maybe three of us,” she said. “I think a lot of time, people give up trying [to access help] because they think they know the outcome.”

Since few Latinos are visiting the intake centers, they often miss out on programs meant to help them in their own communities.

Hildaliz Escalante runs the housing counseling program at Congreso de Latinos Unidos, which gets city funding to run the Rapid Rehousing program, which offers a year’s rental assistance to people. The city sends her the referrals. In the last five years Congreso has served 427 people through the program. Only 42 were Latino.

“We know there are people in our backyard who could use this help,” she said. “But they’re just not reaching us.”

Prioritizing one person over another for public assistance based on race or ethnicity would violate equal-rights laws, but Escalante said she thinks the city can do more to pull Latinos into the intake centers, and by extension, programs.

Hersh said the city is going to pour more resources into outreach in the Latino community and in the coming year will nearly double funding that flows to Latino organizations from 8 percent to 15 percent. In a meeting with Gonzalez and other city leaders Thursday, both parties agreed to do a six-month study looking at gaps in service.

“I think the bottom line for me, is ‘yes, I think we can do better,’ ” Hersh said. “We should do better. We don’t ever want to create a situation where people have to become homeless to access housing, but at the same time we need to be responsive to the unique needs of different communities.”

She said the city is also looking into opening a shelter in Kensington, which has become the heart of the city’s opioid crisis.

While Hersh said she’s looked at two dozen sites, none have advanced.

“We’ve faced tremendous community and political opposition to most shelter sites,” she said.

Councilwoman Maria Quinoñes-Sánchez, who represents the district, said she won’t support a shelter if it houses people who are addicted, because she fears it will entrench the drug problem in Kensington.

“People will [accept] shelters if it’s to help families and there’s a process, but what we don’t want to do is warehouse people,” Quinoñes-Sánchez said. “The residents, as empathetic as they are because everyone has people in addiction, know that the 700 people in Kensington who are addicted are not from Kensington. We put people in shelter beds, we’re facilitating that.”

Hersh cautioned that more shelters don’t guarantee a transition into affordable housing. More effective, she said, are prevention services, for which her office has tripled its budget in the last three years.

“I think sometimes people think if they were able to get into the homeless system that it would unlock this treasure trove of housing opportunities, and that’s just not true,” Hersh said. Less than a quarter of people who enter shelters move into permanent housing, she said. But for those who do, the success rate is 93 percent.

A strict definition of homeless

Advocates like Gonzalez, Diaz, and Escalante say they work with dozens of people who are living from place to place, sometimes in dangerous, overcrowded living situations but who don’t qualify for certain programs provided through the Office of Homeless Services, like Rapid Rehousing.

That program, funded by the federal government, serves only people who meet a strict, federal definition of homelessness: those living in a place not meant for human habitation, in an emergency shelter, in transitional housing, or exiting an institution.

“To be sleeping in a crowded situation, five in a bed, on a couch, is not considered homeless,” said Diaz of APM.

By that definition, the two men, Goytia and Aponte, are homeless. But Bryant, the mother of three, moving from house to house is not.

Quinoñes-Sánchez said that if the definition is what’s keeping the city from reaching Latinos, it’s up to the city to advocate for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to change it.

“We need a redefinition of homeless, and we need additional resources. Acknowledge the data,” Quinoñes-Sánchez said. “The data tells a story.”

Latino organizations also need to help the city come up with solutions, she said: “This has been a problem for years, and this is really the first time these groups have stood up and said something. So I don’t want the system to be blamed if we really haven’t made requests.”

Bryant’s family was making due until she got sick and had to stop working. Her husband, who didn’t finish high school, is the family’s sole income earner. He walks a mile and a half to AutoZone every day. She takes care of the kids and attends night classes to get a degree in social work. Keeping a roof over their heads has been a constant struggle.

They lived with her mother until things grew too tense in the cramped home. They considered shelters, but Bryant didn’t know where she would take the kids during the day, and worried that if the city saw her children didn’t have a stable home, they might take them from her.

Bryant eventually told a teacher at Esperanza College about her family’s situation. Through a web of connections she found a landlord willing to rent her a three-bedroom for $700 a month in a part of North Philadelphia where the shootings unnerve her. She doesn’t know how long they will be allowed to stay. Her backup plan is moving closer to her brother in Florida, where the wait for public housing is shorter.

“That’s the thing about being unstable,” she said. “You have no choice where you live. We haven’t really set up any of the bedrooms, just in case. It’s hard. I feel that we’re overlooked a lot.”

Philadelphia’s homeless services can be reached via a hotline at 215-232-1984 or at http://philadelphiaofficeofhomelessservices.org.

Emma Restrepo is a freelance writer.

Philadelphia Media Network is one of 22 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.

Philadelphia Media Network is one of 22 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.