Why Philly’s Vietnamese community is fighting to save Hoa Binh Plaza

The demolition of Hoa Binh Plaza would close 10 vibrant long-term ethnic businesses, end 50 jobs and eliminate nearly 30 years of service to Philly's many diverse communities.

Vietnamese community members in front of 1515 Arch Street. (Courtesy of 18MillionRising)

On July 24 at 9 a.m., chants of “Whose Streets, Our Streets!” roared at the entrance of 1515 Arch Street. Nearly 100 supporters came to save Hoa Binh “Peace” Plaza of 1600 Carpenter St. from a developer’s plan to replace the South Philadelphia shopping center with a string of townhomes and condos.

Vietnamese refugee elders took three forms of transportation to tell their stories at the developer’s Zoning Board of Adjustments hearing. Neighbors of the plaza who had prepared to testify took off work. One of the plaza’s business owner tenants closed his shop for the day.

Community organizers sat with plaza tenants and the elders of our community with signs that read: “We built this community, We will protect this community.”

We were ready to testify and have our voices heard. Then, Streamline, the developer, requested a continuance with the zoning board, pushing back the hearing on the variance request.

“This is what they do,” said Ms. Melinda Shikomba, executive director of the North of Washington Avenue Coalition., “They delay and delay in hopes that your people won’t keep showing up.”

Losing a community anchor

Hoa Binh Plaza sits in the 19146 zip code, one of the fastest gentrifying zip codes not only in Philly but in the nation. Medium Home value increased from $54,478 in 2000 to $274,424 in 2016.

The demolition of Hoa Binh Plaza would close 10 vibrant long-term ethnic businesses, end 50 jobs and eliminate nearly 30 years of service to Philadelphia’s many diverse communities. For nearby residents who have already been pushed out by gentrification, the plaza serves as an anchor that continues their connection to their neighborhood. Much like uprooting a deeply rooted tree, demolishing the plaza would upset an entire ecosystem that has been built around the communities and businesses that are interconnected with Hoa Binh.

Streamline’s proposal, first reported by PlanPhilly, purports to offer “affordable” units, starting at $240k for 20% of their units. And yet, in a city where the median income is still $39,000 for a family of four, we ask: affordable for whom?

Walking around the plaza, you can see that the nearby new houses have key markers of contemporary development. Gone are the brick facades of Philadelphia row homes, replaced by geometric and boxy constructions. A neighbor of 30 years shared how the plaza has served as a source of food security for her family and how she fears that this project will threaten her own housing security. Many of her neighbors have already been pushed out of this hyper-gentrifying neighborhood.

‘When else have zoning decisions been made without the notice of vulnerable parties?’

When VietLead started working with the business owner tenants at Hoa Binh Plaza, we were faced with a complicated and convoluted system.

When a developer wants to purchase a building and change the zoning, they must seek the approval of the area’s Registered Community Organization (RCO)—in this case, the coordinating RCO is South by South Neighborhood Association (SOSNA). The developer is required to notify residents who live within 200 square feet of the potential development of an RCO meeting. However, out of the 146 houses VietLead door-knocked, only a handful said they were notified of the RCO meeting that took place on June 4.

Worse still, none of the business owners were notified or present at the meeting and yet the vote continued and was approved. Although these meetings are meant to represent community voice, how truly open and accessible are they if directly impacted businesses and next-door neighbors don’t know they are happening?

When else have zoning decisions been made without the notice of vulnerable parties? How often has this resulted in the eviction of tenants and community?

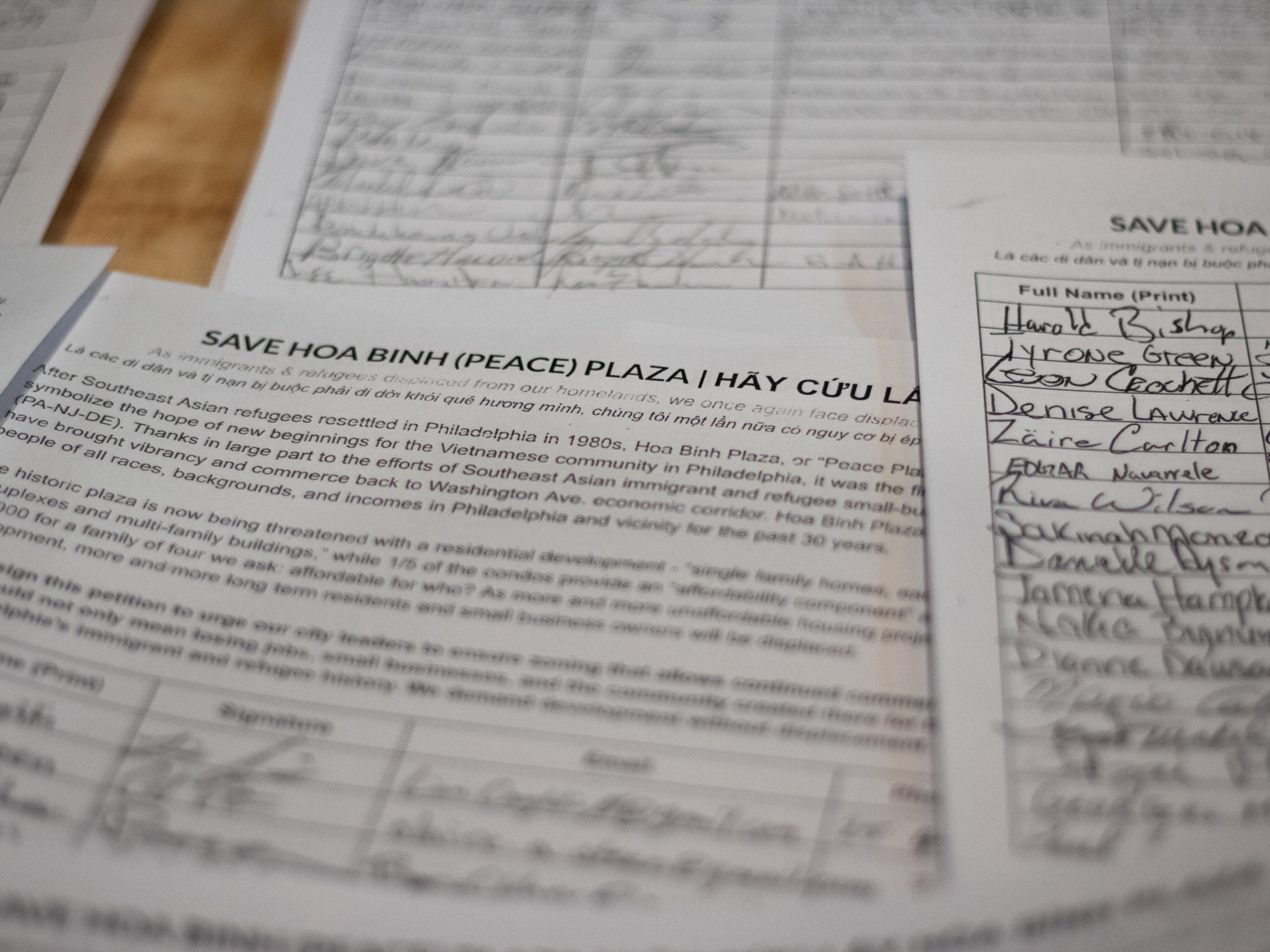

VietLead launched a #SaveHoaBinh petition on June 18, which went viral overnight on social media with thousands of shares and hundreds of comments expressing the cultural importance of the plaza. The petition garnered nearly 12,000 signatures.

Rumors of gentrification pushing out other business owners down Washington Avenue have since ignited. What would the demolition of Hoa Binh mean for the fate of Washington Avenue—home to the Italian Market, Little Saigon, and many Latinx restaurants like South Philly Barbacoa?

At a June 25 rally, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson said, “I don’t see how I could be supportive of this outright evicting all the tenants in good faith, so no, I’m not supportive of just kicking all the businesses out.”

He continued to speak to the roomful of residents applauding at his remarks. “I also recognize that long-term residents should also have carte blanche on the cultural development of the neighborhood because, at the end of the day, these businesses were here on this avenue when other people didn’t want to invest on this avenue,” he said. “And that’s why they should have first say as to what happens as we move forward.”

We agree with Councilman Johnson that we need to put people before profits when considering any changes to the city. With the power of councilmanic prerogative to have final say over the use of land in the city, Councilman Johnson has much influence over the fate of the plaza. We hope to continue to work with him to make sure our community can get the final say in this development.

‘They have seen our power’

Streamline’s proposal has been met with widespread resistance from residents, community organizations and some city officials. The city’s Planning Commission and NOWAC—another RCO in the area, voted against Streamline’s plans. In the days leading up to the hearing, SOSNA walked back its vote from approval for the zoning variance to a neutral position.

The fight to save Hoa Binh has become emblematic of the broader struggle between private interests and the public good. The valuing of land use that prioritizes cultural preservation, community health, jobs, and truly affordable housing to meet the needs of working-class communities of color is critical to an equitable and “diverse” Philadelphia that our city claims to be.

“How often are these zoning hearings packed like this,” I asked the staffer ushering the dozens of Hoa Binh supporters out of the zoning hearing room into the hallway. “Every week now it seems,” she responded.

We can’t help thinking that this is a good thing. Philadelphia is literally changing before our eyes. What we’re seeing with Hoa Binh is similar to what is happening with so many other parts of the city, including Hahnemann Hospital. We are seeing private interests, capital and development pushing out long-time communities and businesses, facilitated and accelerated by policies from the city such as the 10-year tax abatement. These fights ultimately come down to one question: Who does Philadelphia belong to? That is, who gets to decide the present and future of Philadelphia?

As we left the ZBA hearing after the continuance was decided, Mr. Tuan—the owner of Nam Son Bakery patted my back. He told me not to worry. “They have seen our power,” he said.

Philadelphia is transforming—and so are we, as organizers, cultural practitioners and entrepreneurs. We need new processes and protocols in this city that keep working-class, black, brown and immigrant communities intact and in place. We will continue to keep showing up and continue to fight to save Hoa Binh. We demand development without displacement.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.