What you see can’t be ‘Unseen’: NYC photographer takes us backstage in the Mütter Museum

Photographer Nikki Johnson got a backstage pass to roam the diseased body parts not seen by the public at the Mütter Museum.

Forensic photographer Nikki Johnson spent years in the storage rooms at the Mütter Museum. The resulting work is displayed in 'Unseen,' an exhibit that will run through Sept. 30, 2021. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has about 1,000 objects on display related to body parts and human pathology, which enlighten, educate, disturb, and give you the plain ol’ creeps — a skull with a horn growing out of it, a coal miner’s lung in a jar of ethanol, genital warts strung together like a necklace.

That is just the tip of the iceberg. What visitors are allowed to see is only about 8% of what the Mütter holds in its vast collection of mostly 19th-century medical oddities.

“Like most museums, we only have a fraction of our collection on display,” said curator Anna Dhody. “Some things will never be on display.”

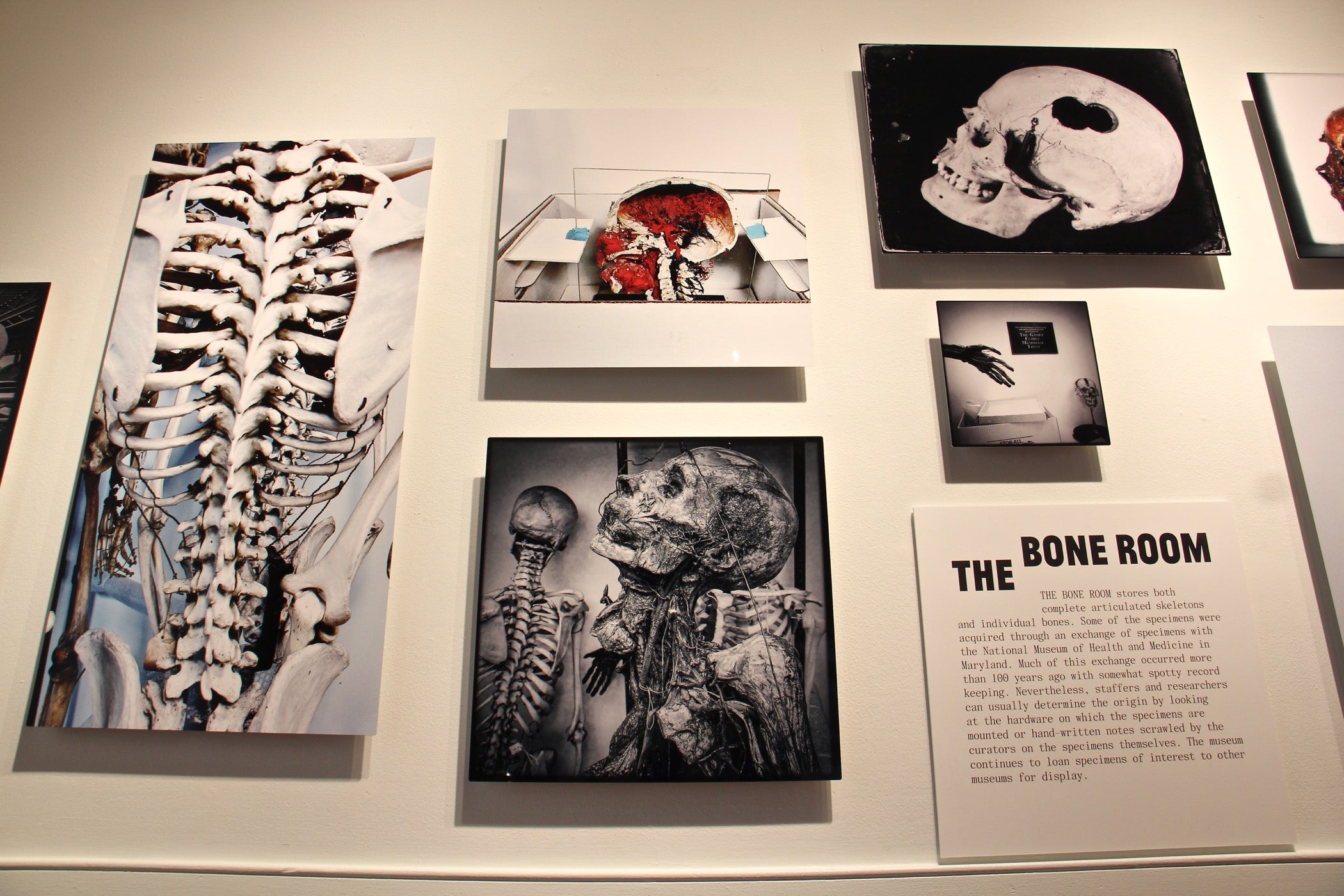

Closed to the public, the Bone Room, the Wet Room, and the Stacks have artifacts that are too fragile, damaged, or dangerous to put on display. Some tissues have been floating in chemical solutions for over 150 years and need specific climate conditions to keep from deteriorating. Some emit fumes that can be harmful to visitors.

To bring those artifacts to the fore, the Mütter brought in Nikki Johnson, a fine art photographer from New York City who earns a living as a forensic photographer, documenting autopsies and medical evidence. She was given free rein to roam the back rooms and take pictures of whatever she wanted.

“The work I do on a daily basis will never be seen by anyone, other than in court,” Johnson said. “Whereas this had more of an artistic appeal.”

Unseen is an exhibition of Johnson’s photos, on display in the Mütter’s Thomson Gallery. Among her pictures is a corpse that had been subjected to a controlled corrosion, so only the circulatory system remains, for study. The head is propped upright with a wire. The figure resembles an extra from Walking Dead in an advanced stage of decomposition.

A picture of a fetus in a jar of solution ignores most of the specimen and focuses only on the feet, and the way they curl under the knees.

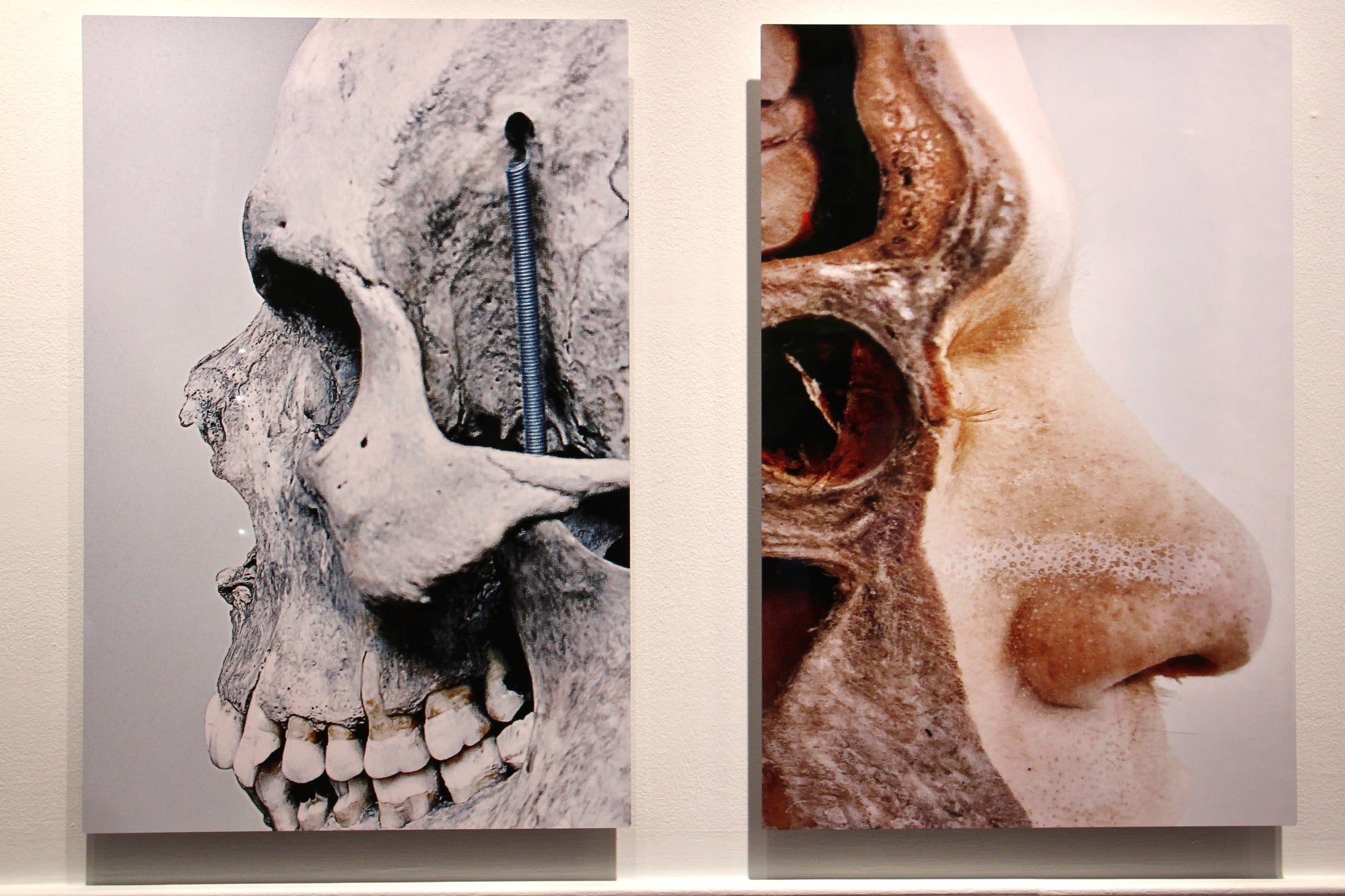

Johnson took photographs of a human head that had been sliced into thin cross-sections so the structure of the cranium can be seen, but she chose to frame just the nose and what’s left of the eye socket. In the close-up, you can see a tuft of nose hair and an eyelash.

The remains of hair bring the medical artifact into human terms.

“This is a specimen, and also very much a person,” Johnson said. “It’s kind of a meditation on mortality.”

The Mütter Museum did not need Johnson to document their backroom specimens; They already take their own photos for archival purposes according to scientific standards. A skull, for example, needs to be photographed in a very particular way so the images can be put into a database and shared with other researchers.

The museum wanted Johnson to use her artistic eye.

“What I love about Nikki’s work is it’s beautifully illustrative, and still artistic,” Dhody said. “It combines these things.”

Johnson managed to find pops of color in this gray, morbid world. Preservation solutions are bright yellow, lungs are injected with red dye to show off their capillaries. She also made visible the staff that maintains the artifacts, photographing Post-it notes the conservators leave for each other on jars filled with dead things.

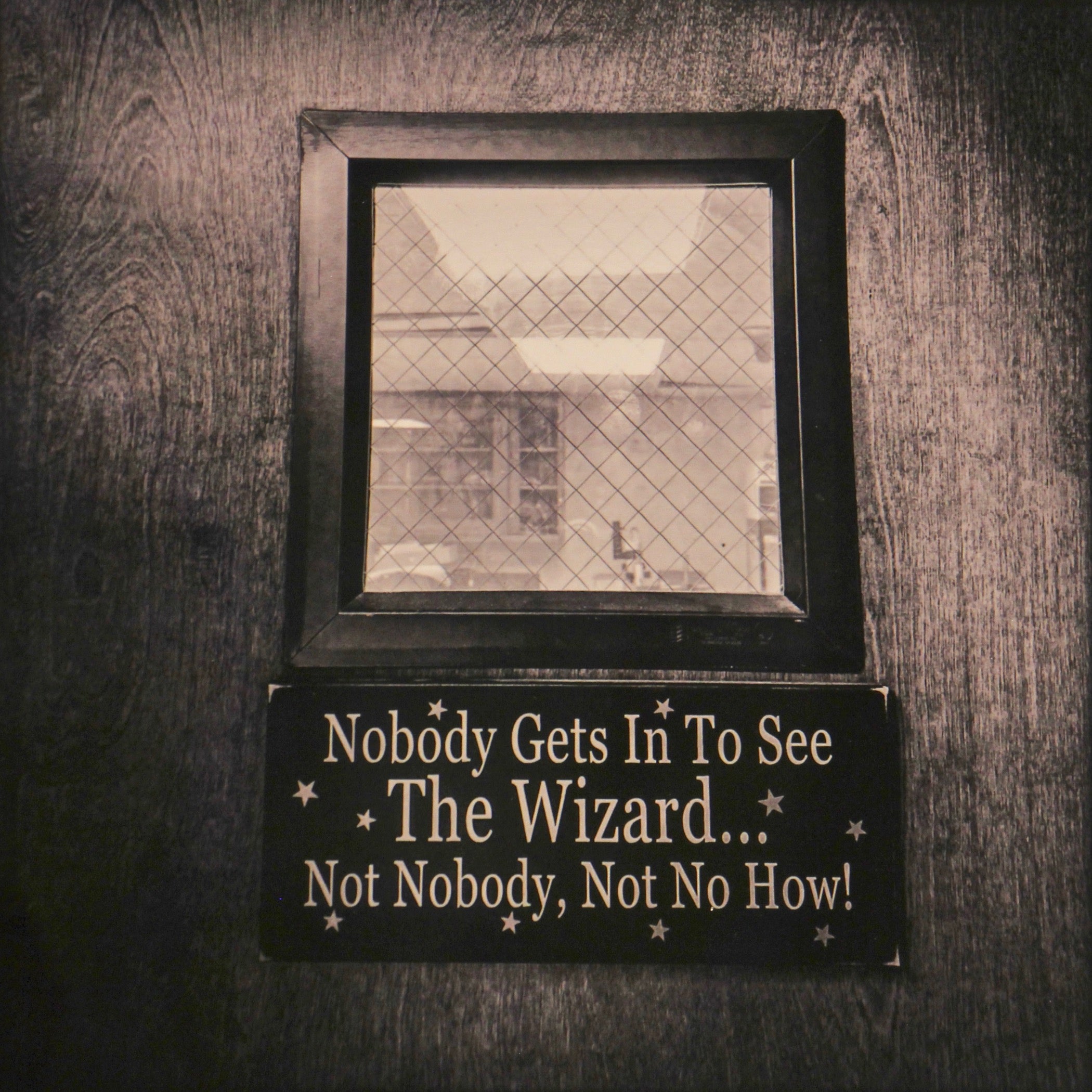

“It’s the sense of humor people have in any workspace,” she said. “It lets you know you’re truly inside.”

Although most of the collection was collected from 19th-century doctors by the museum’s namesake, Dr. Thomas Mütter, the institution still acquires new artifacts. Dhody admits that those earlier acquisitions were sometimes not in accordance with modern medical ethics – or even the ethics of their own time.

“I collect in a different way. I collect from patients themselves,” said Dhody, who has acquired amputation and transplant organs through arrangements made pre-surgery, or, in the event of a whole skeleton, pre-death.

“Over the summer, I got my first human heart from a heart transplant patient,” Dhody said. “I’m so excited. I have the full consent and enthusiasm from the donor.”

That heart, the bad one removed from a donor in New Orleans, is part of the photography show, seen floating in its own jar of fresh solution.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.