What’s driving Philly’s rising land values?

What’s vacant land in Philly actually worth?

Kevin Gillen, the chief economist of Meyers Research, and Guy Thigpen, director of analytic services for the Philadelphia Land Bank, gave a presentation at the Pyramid Club last week showcasing the model of the Philly land market they developed with Lindy Institute Fellows, with an eye toward the policy implications for disposition of vacant city-owned land.

Why should anyone care about the land market? Isn’t that just the same thing as the housing market? Not exactly.

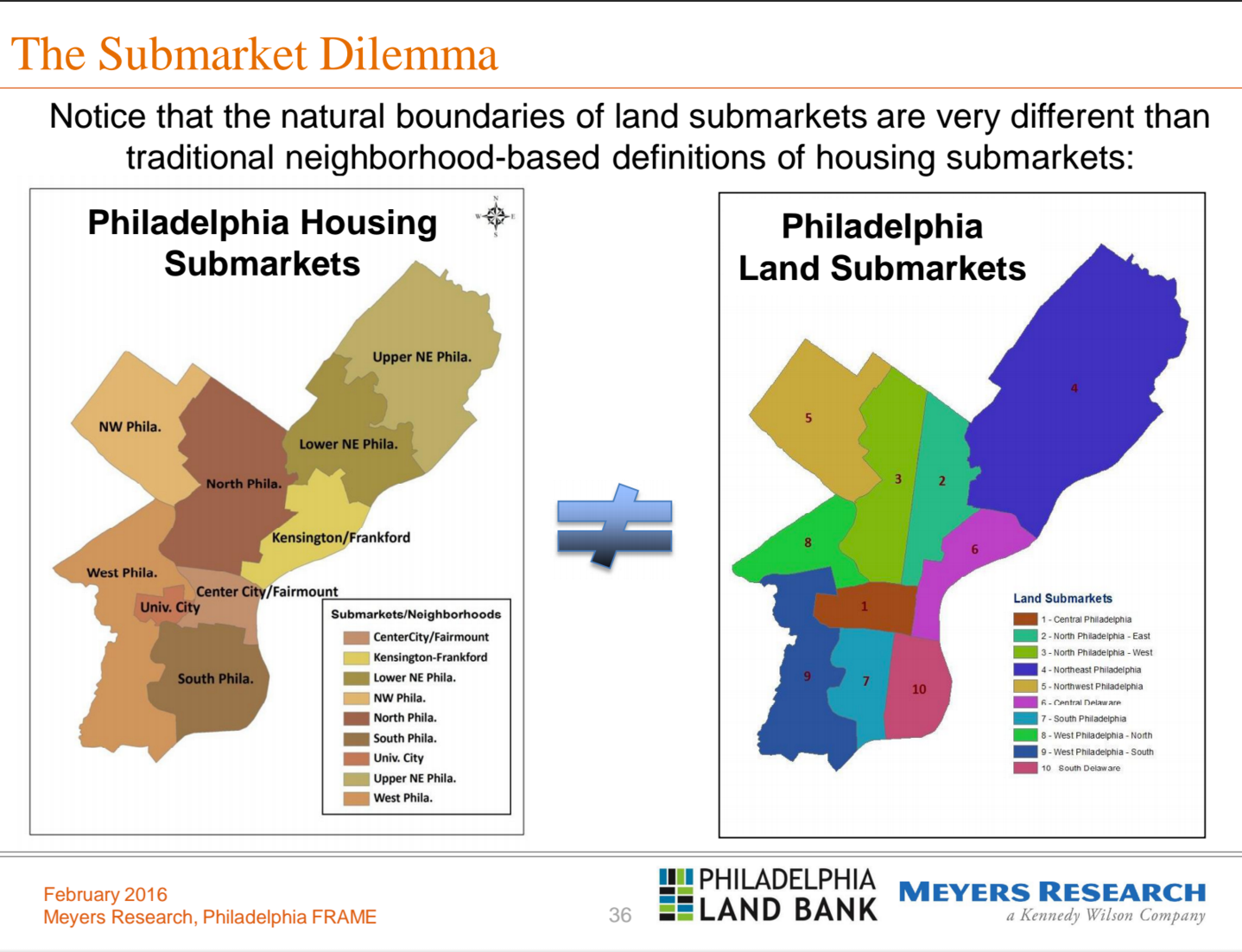

“Oftentimes we just assume that land markets are the same as housing markets,” explained Thigpen. “Certain neighborhood housing markets are seeing an increase, and we just assume that the land markets are following the same trend.”

Land has more of a speculative quality that owes mostly to its location. For example, all the different nearby amenities around a land property affect its value, but it’s also common to see land prices increasing in places that are just anticipated to attract more amenities.

“But in fact, land markets actually follow a trend where they expand faster than housing markets,” Thigpen continued. “You have to buy the land first and then you build the house, so you get speculation on land in certain neighborhoods that may not be turned over or gentrified.”

The whole business of modeling land values and submarkets is fraught with issues that bias the data in one way or another.

Since vacant land parcels don’t change hands as frequently as houses, indexing land values is more difficult and less exact than indexing housing prices, for instance. Some places, like North Philadelphia, see more vacant land transactions, making it easier to create an index, whereas built-out neighborhoods with fewer land sales like Center City and South Philly are more difficult.

But through various modeling tweaks (too wonky even for PlanPhilly), Gillen and Thigpen successfully created a working up-front land valuation model which they find comes remarkably close to predicting land sale prices.

Here are a few of their findings :

Location, Location, Location

The value of land “is determined almost solely by its locational variables,” said Gillen, “Once you know the square footage of a parcel, its frontage and its depth, maybe its topography, that explains maybe 20% of what it would go for in the market. The rest is determined by its location.”

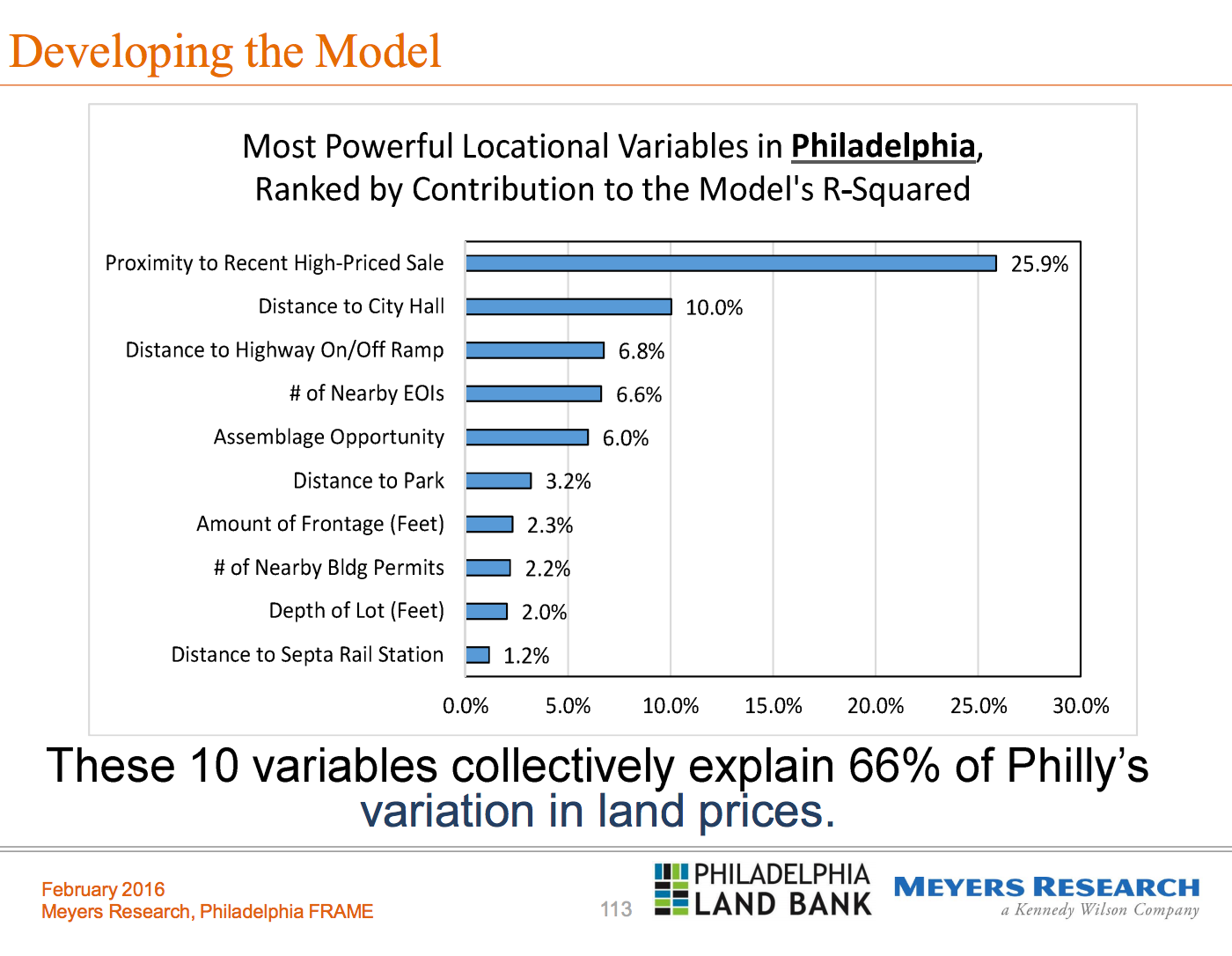

After testing around 300 different potential variables, it became clear that only a relative handful of characteristics really explained differences in land values. They identified 10 locational variables that together explain about 66% of the variation in Philly land prices.

Nearby price comparisons are the biggest predictor of land value, as are the number of expressions of interest (EOIs) and nearby building permits. Not surprisingly, people want to buy land near where others are buying and developing land, and they want to pay close to what others are paying.

Proximity to City Hall was another major factor, likely more because of its centrality to amenity-rich Center City. Other attributes like convenient transportation access (highway ramps or SEPTA rail stations) and parks also added value.

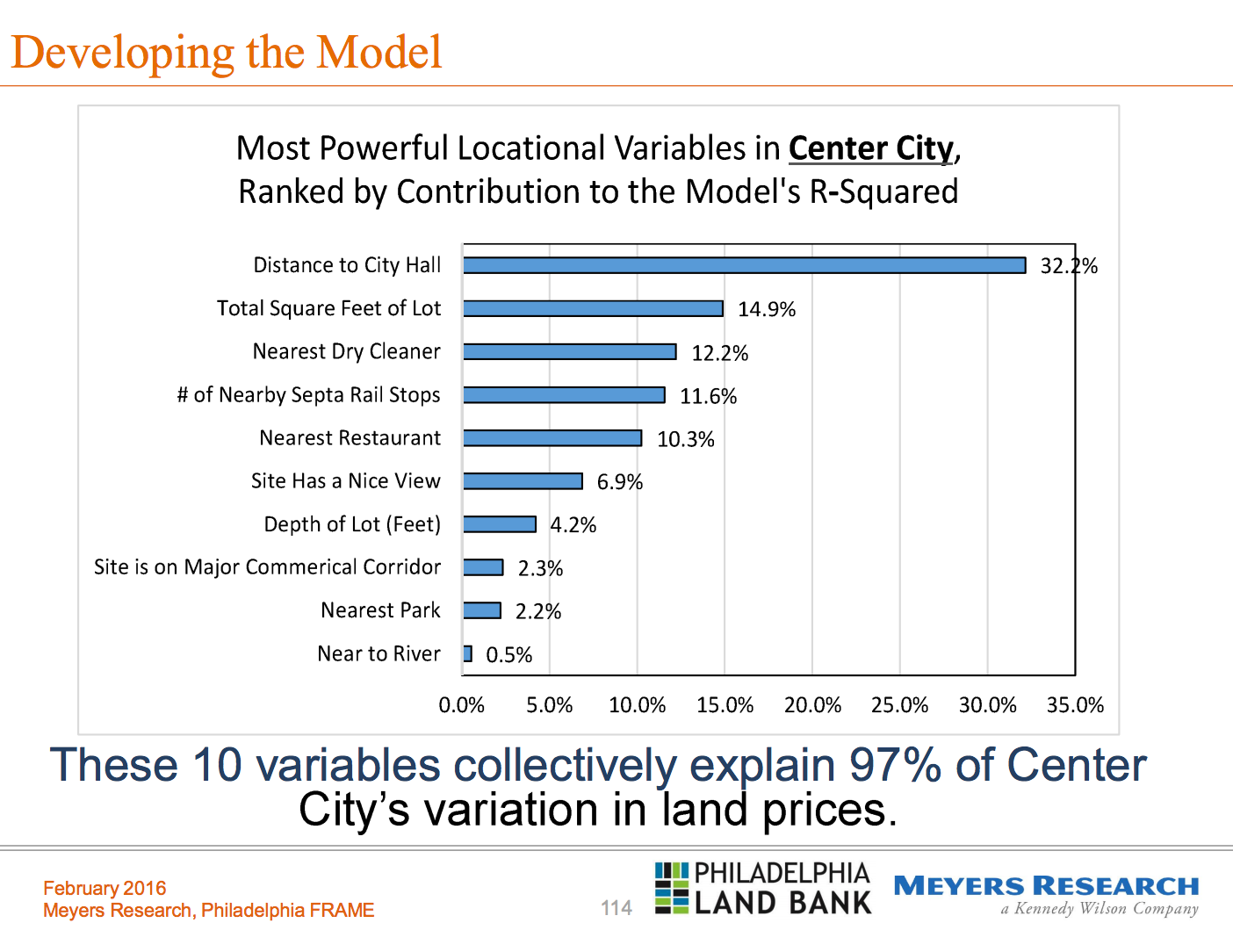

Of course, the attributes that matter to land buyers vary between different areas of the city. As an example, Gillen showed the breakdown for two different land submarkets: Center City and North Philadelphia.

In Center City, the highest land values are closest to City Hall and they diminish further away. Large lots, which are generally harder to come by in Center City, also sell for more.

Fascinatingly, proximity to a dry cleaner was the third most predictive variable, followed by the number of nearby SEPTA rail stops, proximity to the nearest restaurant, and nice views. There’s also a price premium for parcels located on major commercial corridors, or close to parks and rivers.

In North Philadelphia, the major correlates of value were different: proximity to a recent high-priced sale, Sheriff sale properties, assemblage opportunities, highway access, and proximity to a university campus were the most predictive characteristics.

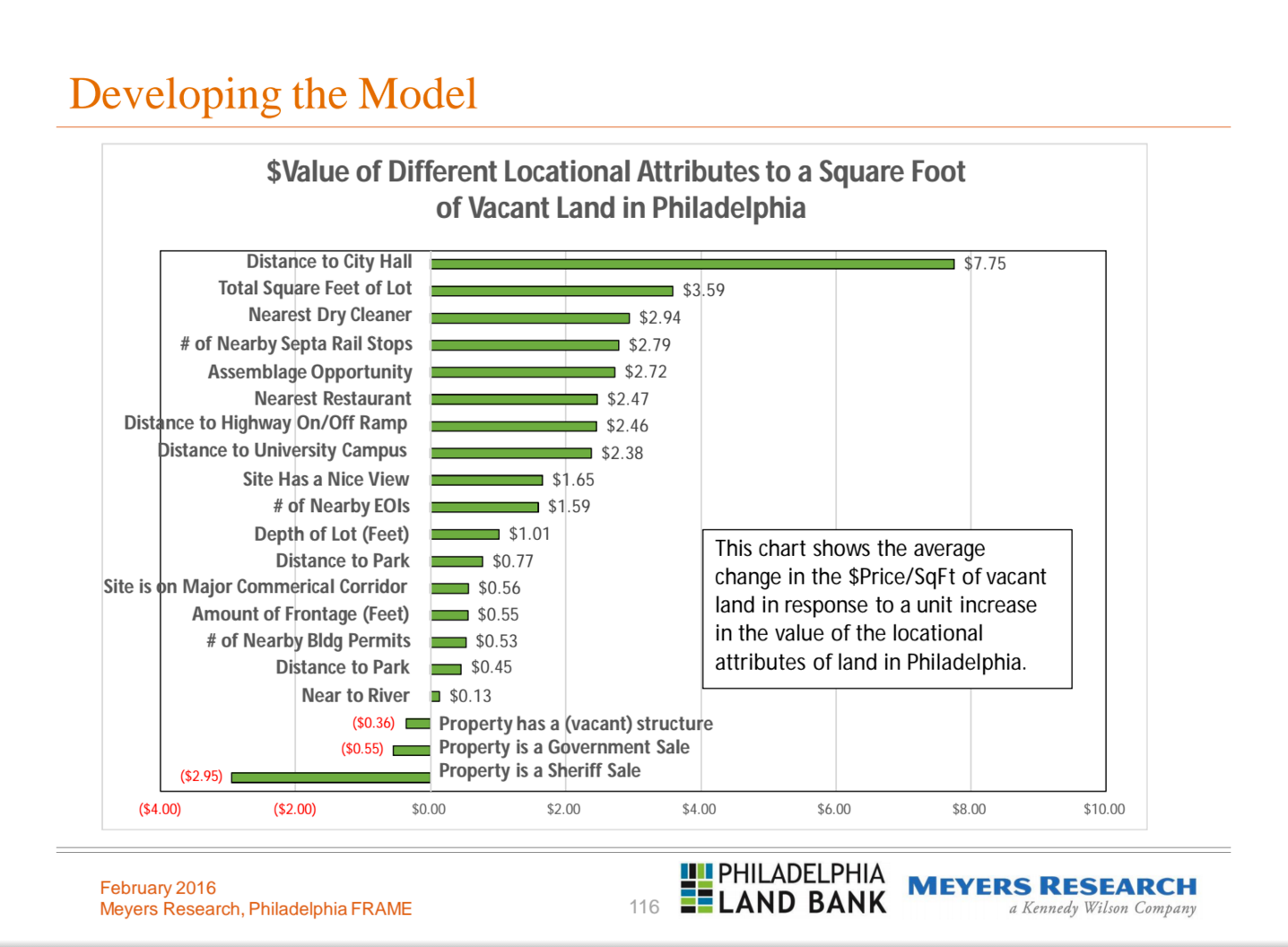

For a more concrete visualization, Gillen included this breakdown expressing the value add of different variables as a dollar amount:

The qualities that tended to depress land value were the presence of a vacant structure, or appearance on a government land sale list.

Zoning has no impact

Amazingly, zoning had no correlation with land value.

“We tried zoning,” said Gillen. “Zoning would not explain land values whatsoever. There was no statistically significant relationship between what a parcel was zoned as, and what it was transacted for.”

Zoning, in theory, is supposed to determine what you can do with a parcel. Shouldn’t that influence land value?

“Very rarely does a parcel sell in the city which is developed according to what it was originally zoned for,” Gillen explained, “Most of the time, the developer who bought the parcel will go and get a zoning variance. The joke around the office was that Philadelphia doesn’t have a zoning code; it has zoning suggestions.”

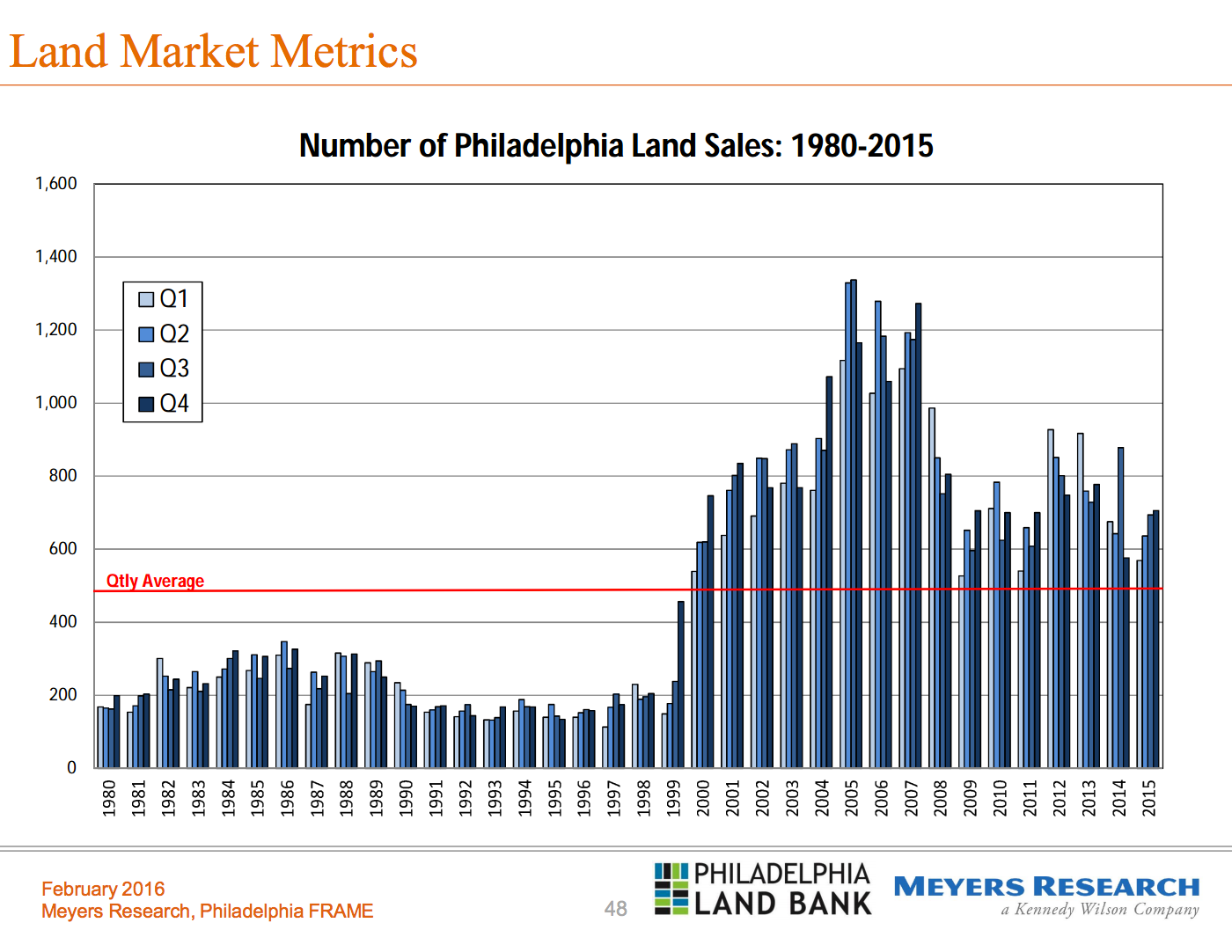

A big jump in land sales

Only a few submarkets account for a majority of the volume of land sales: South Philly, West Philly, and North Philly.

There are very few land sales in Northeast Philly, Northwest Philly, deep South Philly, or areas of far West Philly.

Gillen pointed out the large level change in the number of land sales in the year 2000, crediting the 10-year tax abatement on site improvements for the increase in sales volume.

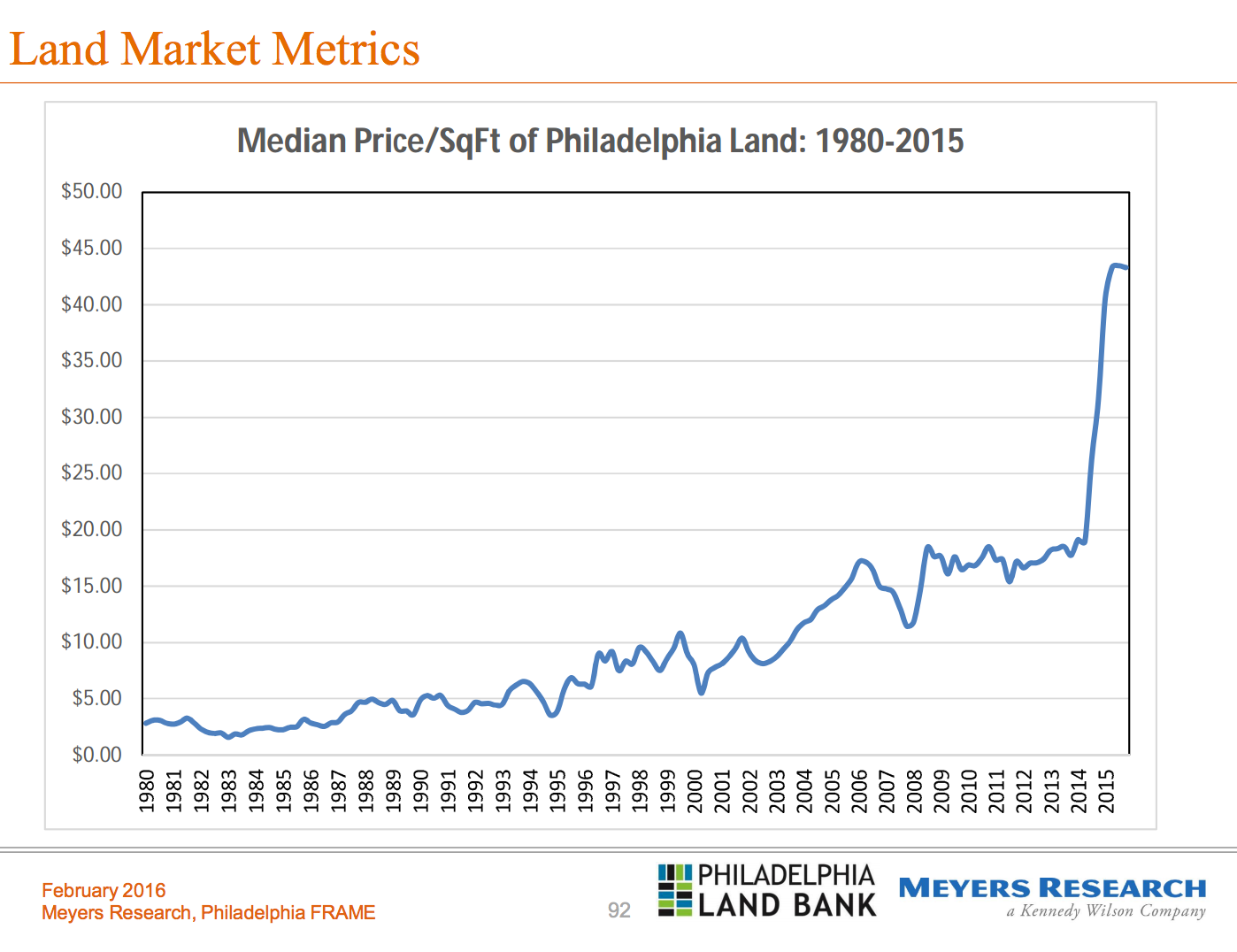

Median land prices spiked in 2014

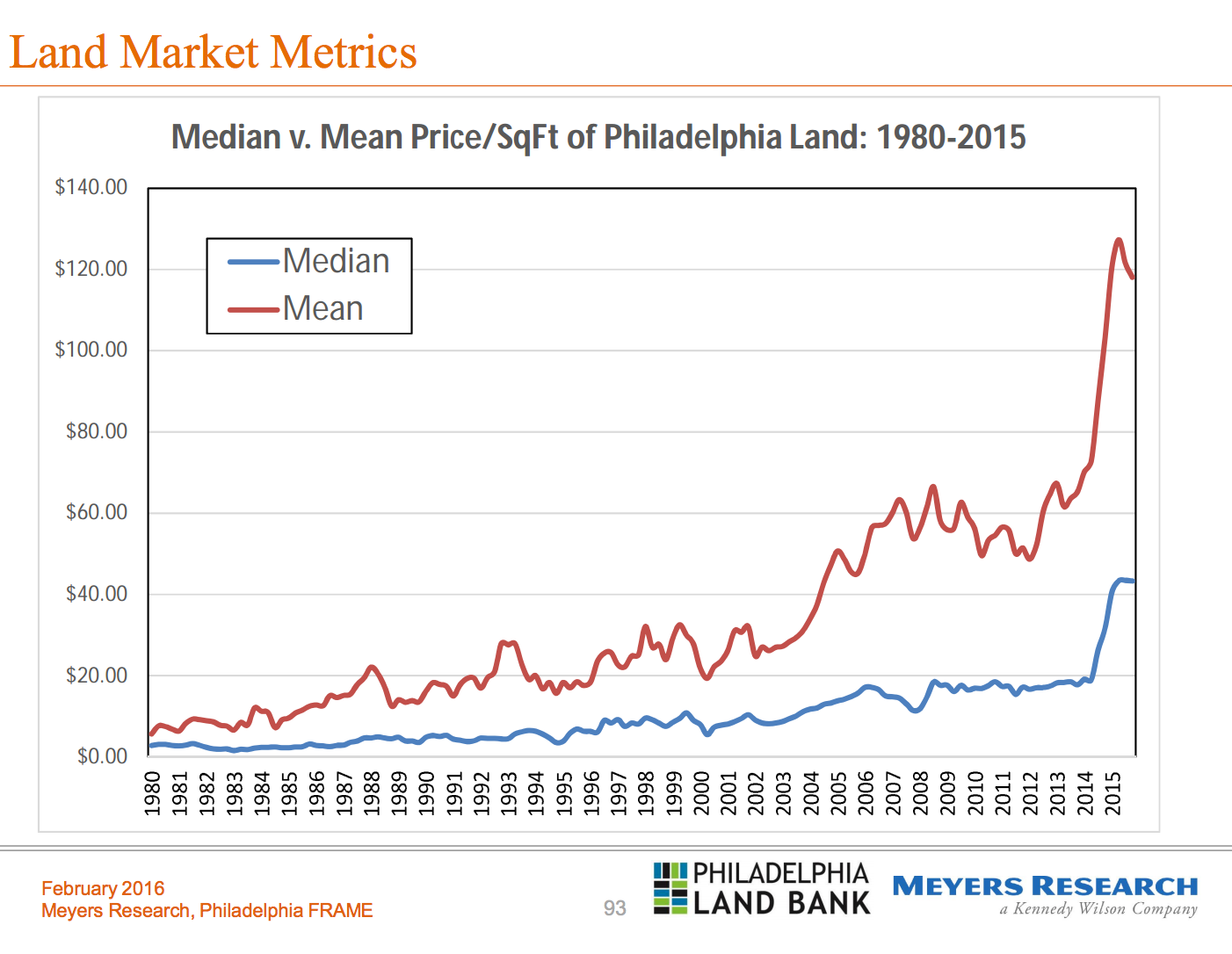

There is a huge variation in Philly land prices, and the spread resembles a “long tail” where 25% of city land sales in 2015 went for $25 a square foot or less, while the top 25% sold at a price of $130 a square foot or more. On the high end, one percent of all transactions sold at a price point about $888 a square foot or more.

To put that in historical context, in 1980, the median price of a land parcel in Philadelphia was about $2.50 a square foot citywide, and even by the peak of the housing boom in 2007 it was only up to about $15-17 a foot.

During the downturn, prices were fairly flat between 2008 and 2013, but in just the last two years, the median price in the city jumped to almost $45 a square foot.

“We vetted this for months,” Gillen said. “We had trouble swallowing this one. If it’s wrong it’s because the city’s data is wrong, and Guy and his team vetted it as best they could…There was a very large spike in prices in land transactions in Philly over the course of the last two years.”

The trend line for the mean (average) price is even more dramatic. Mean prices were less than $5 a square foot back in 1980, rising to $60 by 2007, and now are up to $120 a foot.

Gillen said this is a function of a very high concentration of relatively small parcels transacting for very high prices, and pulling up the mean price.

Again, there is a huge variation. The bottom 20% of land sales in the city transacted at a price point of $10 a foot or less on average, while the top 20% transacted at a mean price point of $180 a foot.

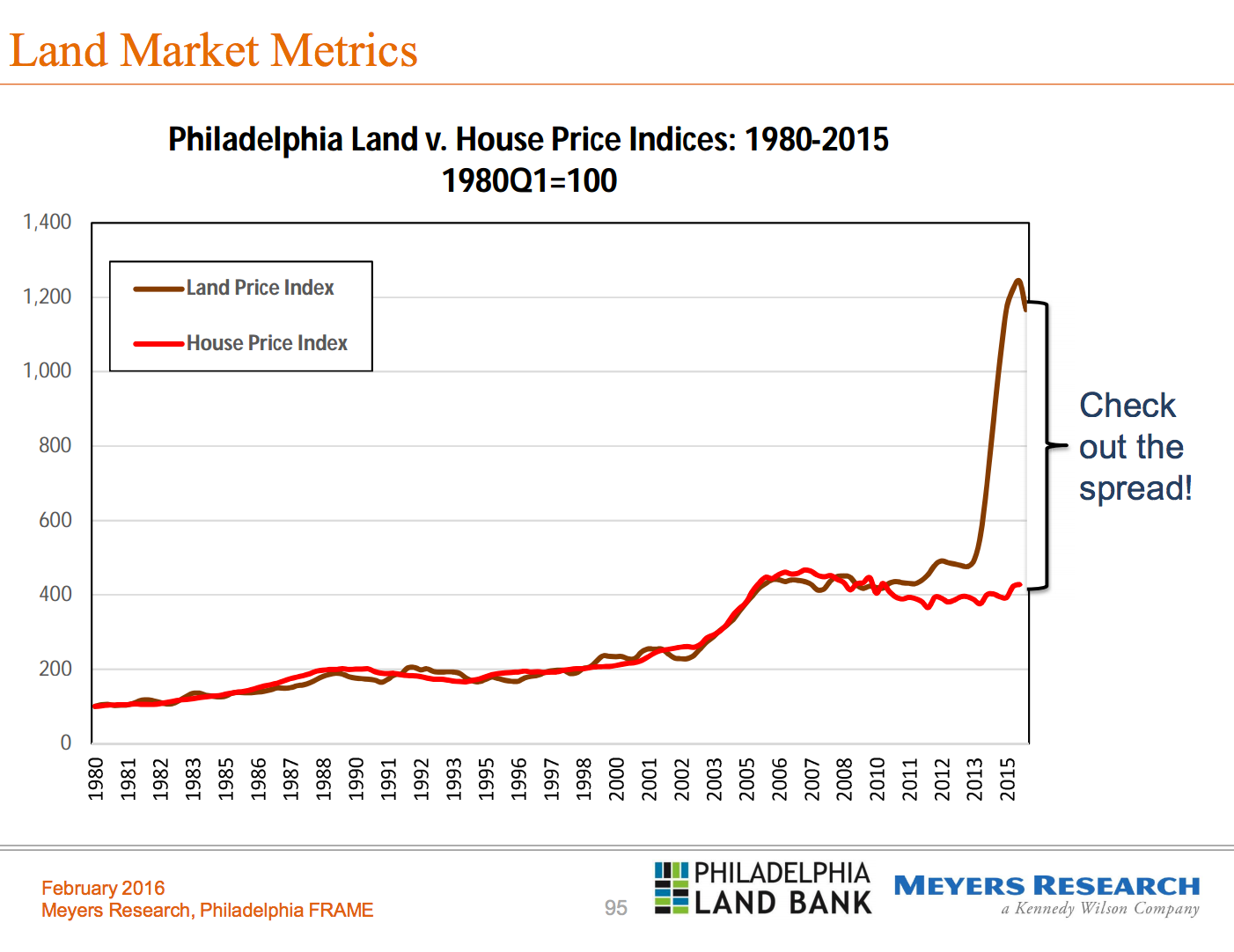

A visual comparison with the trend in home prices over the same time period shows that while land prices and house prices tracked closely together for a long time, land values have really broken off over just the last few years.

Policy Takeaways

Gillen noted that assembling groups of smaller parcels into larger parcels can increase land values, which he recommended as a strategy the Land Bank could use to increase the value of its holdings.

The presence of an available adjacent parcel increases the value of a land parcel anywhere between 5 to 15% depending on the location, said Gillen.

“This has a very strong policy implication because the city can actually create value by assembling parcels so that developers don’t have to,” he said, “That is the number one thing the land bank could do, with its authority, to create value.”

Past performance can’t predict the future, but barring any major unexpected setbacks, Philadelphia’s land market should remain on an upward growth trend, said Gillen.

His second takeaway was that while many city-owned land parcels are in markets that are currently depressed, many of these are in the path of growth, and before long, could be sold into appreciating markets.

“Many city-owned land bank parcels are very tightly clustered around where values are growing, and historically speaking, the value is expanding outward from Center City,” he said. “So while these parcels may not be very large in terms of square footage, a significant number of them turn out to be right in the path of current growth, and the timing couldn’t be better.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.