What happened to Abdullah Pitt? Camden family struggles to get answers

Abdullah Pitt, 20, died one year ago after losing consciousness on the River Line. As his grandparents searched for answers, they learned of the countless lives he touched.

Gordon and Deborah "Zola" Miles, who raised grandson Abdullah Pitt and his siblings, at their Camden home with pictures of Pitt in October 2021. (April Saul for WHYY)

Abdullah Pitt loved the River Line.

It was the motion of the train that runs from Camden to Trenton that enraptured the young man, who was on the autism spectrum.

“He loved that train and rode it up and down, up and down,” said his grandmother Deborah “Zola” Miles, though “his ability to read and comprehend wasn’t there for him to know where he was getting on and off.” Once, when Pitt first started to ride, he was ticketed for not paying the fare, not realizing he was supposed to, and Miles had to go to court to get the charge dismissed.

It was on his beloved train that the Camden 20-year-old lost consciousness on Dec. 17, 2020, and died shortly after of heart failure.

It has taken nearly a year for the grandparents who raised him, Deborah and Gordon Miles, to get answers about his death — and they say it is only because of the efforts of the New Jersey Crime Victims Law Center that they have the slightest idea of what happened.

According to the autopsy report, Pitt — not known to have used drugs — died because he had ingested a small amount of fentanyl. How he got it remains a mystery.

Since Bancroft School in Mount Laurel where Pitt was a student was closed last December because of the COVID-19 pandemic, his routine was to get up early to volunteer at the Promise Neighborhood Family Success Center — at times so early, said Deborah Miles, that “he’d leave before dawn and be on their doorstep until they opened the door.” Pitt often didn’t reappear until after dark, but the couple was worried by the time a police officer knocked on their door some time after midnight to tell them he had died. They later learned Pitt had been riding the River Line in Camden when he lost consciousness, possibly sometime between 8 and 9 p.m.

First, the couple said they heard their grandson was at a Trenton hospital. Before they could get there, they were told he’d been moved to one in Burlington County. Ultimately, said Deborah Miles, “we never got to see Abdullah until he was in the coffin.”

In the months that followed, the family found themselves in an informational abyss. The ID in Pitt’s wallet had led police to their Camden address, but that and any other belongings disappeared before his body arrived at the funeral home. Even though Camden County police had come to their door, no report seemed to exist.

“Nobody,” said Deborah Miles, “would admit that they took his body off the train … Everybody told us, ‘He’s not in our system.’”

When she rode the River Line to the Trenton police station in an unsuccessful attempt to get information, Miles said she noticed a half-dozen mounted cameras on the train; wouldn’t there be a record of what happened?

Miles turned to Gwendolyn Cook, her supervisor at Cook’s Women Walking in the Spirit mentoring program. Cook enlisted the help of the NJCVLC, which, like WWITS, is supported by Victims of Crime Act funding through the office of the NJ Attorney General.

Richard Pompelio, who founded the NJCVLC with his wife in 1992 after their own son was murdered, took on the challenge. He said he’s lost track of how many Open Public Records Act requests he and fellow lawyer Dyanne Veloz Lluch submitted in an effort to give the Miles family answers.

Lluch said she reached out to prosecutor’s offices in three different counties, to NJ Transit, and to others. Finally, the Mercer County prosecutor’s office gave her an incident report that showed which train Pitt was riding. That led her to obtaining body camera videos from the paramedics who worked unsuccessfully to revive Pitt. She has also requested that NJ Transit provide footage from video cameras on the train, but is still waiting for that.

The medical examiner ruled Pitt’s death accidental, which Lluch thinks might have led to less scrutiny.

“I suppose because there was no evidence of foul play,” said Lluch, “this is just some kid that passed away without answers. Because there’s not a crime, there’s no further investigation. And law enforcement is really overwhelmed with overdoses.”

‘He was pure kindness’

As the family searched for answers, they learned something unexpected: that their grandson — who they already knew had a “very large personality” and “giant smile” — had touched countless lives.

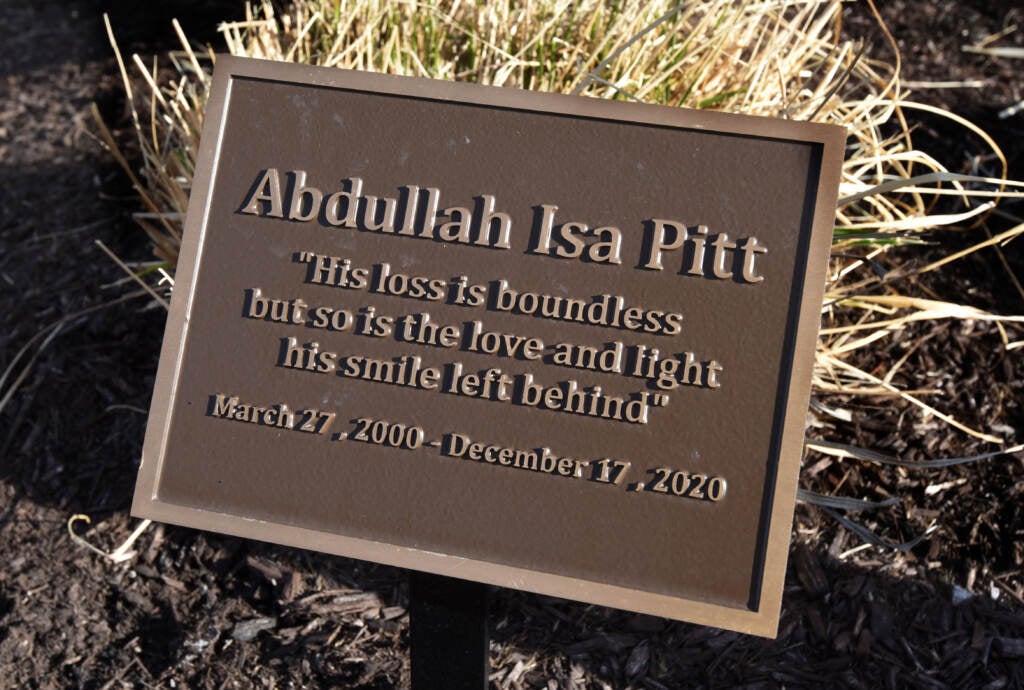

Pitt was so beloved that his death caused ripples of grief from Camden, where he was an avid volunteer for several organizations, to Mount Laurel, where he was such a popular Bancroft student that a balloon release was held and a plaque dedicated in his memory. A crowdfunding effort to raise money for his funeral was satisfied within 24 hours of its posting.

Tracey Miller, a program director at the Promise Neighborhood Family Success Center — part of the Center for Family Services — was devastated by the loss. Miller knew Pitt for five years as “just the sweetest human who was always there to lend a hand.”

“We always worried about him,” she said, “because he walked everywhere by himself and we were afraid he’d be victimized, so we always gave him rides to make sure he was safe.”

Cooper Medical School of Rowan University student Teresa Skelly, who met Pitt in the Homework Heroes program, a collaboration between Promise Neighborhood Family Success and her school, said Pitt “exuded joy” and was the “anchor” of the group.

He was so well-liked, she said, that “we would fight over who got to work with him!” Being told of his death, she said, “was one of the worst phone calls I’d ever received.” The medical students started a chain to notify each other, she said, “and every single person was crying on the phone and was just in shock.”

“He was pure kindness,” said Skelly. “The thought of anyone doing anything to him is just unfathomable.”

No one who knew Pitt — who never had much money on him and who told his grandmother he was afraid to carry his cell phone for fear it would be stolen — believes he purposely took the drug that killed him.

“There’s no way,” said Miller, “that boy knowingly took fentanyl.” She said she’d gotten into an argument with a friend of hers, a South Jersey prosecutor, who told her the River Line “was nothing but drugs.” Miller believes “someone must have tricked him or tried to get him to take it so he would want it again … He would have taken a lollipop or a candy in five seconds flat.” Miller said her prosecutor friend looked for records of the death and found none.

Miller believes Pitt’s death might have been treated differently by law enforcement if he had not been a Black young man from Camden.

“He didn’t deserve it. He didn’t hurt a fly … Someone needs to care that this happened to an innocent person,” she said.

Pompelio also believes Pitt “deserves better.”

Recently, Lluch received body camera videos from paramedics, who arrived at the train when Pitt still had a pulse, and worked to revive the young man.

For Deborah Miles, seeing the video of paramedics attempting to resuscitate her grandson was as frustrating as it was heartbreaking, and raised more questions.

Although the first responders are heard discussing using Narcan, it does not appear to show them treating him with the life-saving nasal spray for opioid overdose victims used widely by police officers and paramedics. “Why didn’t they administer Narcan?” asked Miles. “Or did they and we didn’t see it?”

Last Friday, Gordon and Deborah Miles, along with their daughter and two of Pitt’s siblings, stood outside Bancroft School near a plaque dedicated to Pitt. They shared memories of the young man with educators, including Bancroft principal Patrick Senft, who called the loss “a gut punch.”

Pitt’s former teacher, Holly Blackiston, told the family that even after Pitt’s passing, all who knew him wore pink in his honor on the day he would have turned twenty-one; his birthdays were so special to Pitt that he reminded everyone of them months in advance.

Deborah Miles told the educators, “He went to graduations, proms, he had a life. Abduallah had a life because Bancroft made it possible.”

“We miss him very much,” said Blackiston.

Miles gave her a hug. “The whole struggle,” she said, “is to keep them safe.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.