‘We’re fighting for a public health safety issue’: Pa. nurses unions went toe-to-toe with management on hospital staffing ratios

The pandemic laid bare issues of nurse-to-patient levels in the region’s medical systems. As new contracts were negotiated in 2020, this was a top concern.

Listen 5:29

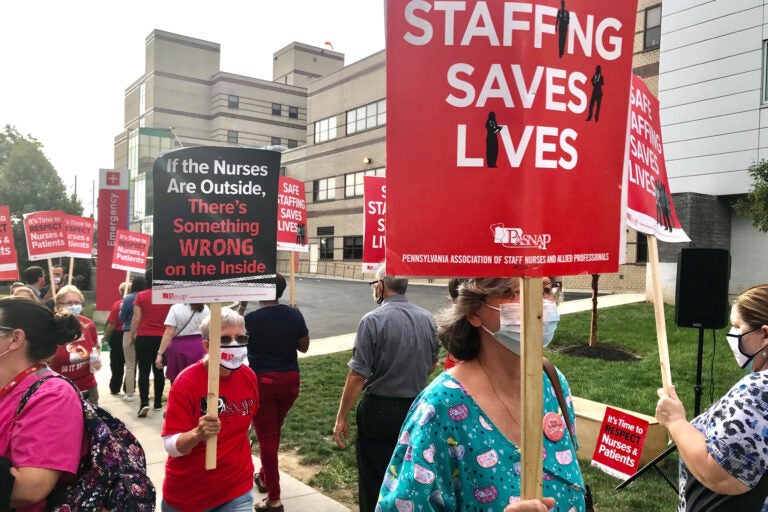

Nurses at St. Christopher's Hospital for Children held an informational picket in September 2020 and staffing was the main points of emphasis. (Courtesy: PASNAP)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

As health care workers battled the coronavirus in 2020, the pandemic laid bare issues of nurse staffing at the region’s medical systems. What was a point of debate pre-pandemic became front-and-center as patients suffering from COVID-19 inundated hospitals.

Nurses negotiated new contracts at Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia, Mercy Fitzgerald and Crozer Health hospitals and nursing facilities in Delaware County, St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia, and St. Mary’s Medical Center in Langhorne last year — and staffing grids were the primary concern of union leadership.

Staffing grids are essentially standards that determine how many patients a nurse can take care of in a given hospital unit. For example, in an intensive care unit there may be a 2-1 patient-to-nurse ratio.

“It was hard, especially in the ICU. We should be a 2-to-1, one nurse to two patients. There were times we needed to be at one nurse to one patient, depending on the condition of the patient — and there were times that we would have three patients,” said Sharon Byrnes, an ICU nurse at Delaware County Memorial Hospital in Drexel Hill, referring to the crush of COVID cases.

Studies show that, for nurses, adequate staffing grids can reduce burnout. For patients, proper nurse staffing is associated with better health outcomes. Poor staffing ratios are correlated with a higher occurrence of infection in hospitals.

Most nurses unions in the Philadelphia region, however, have found that staffing grids can be hard to nail down in contracts.

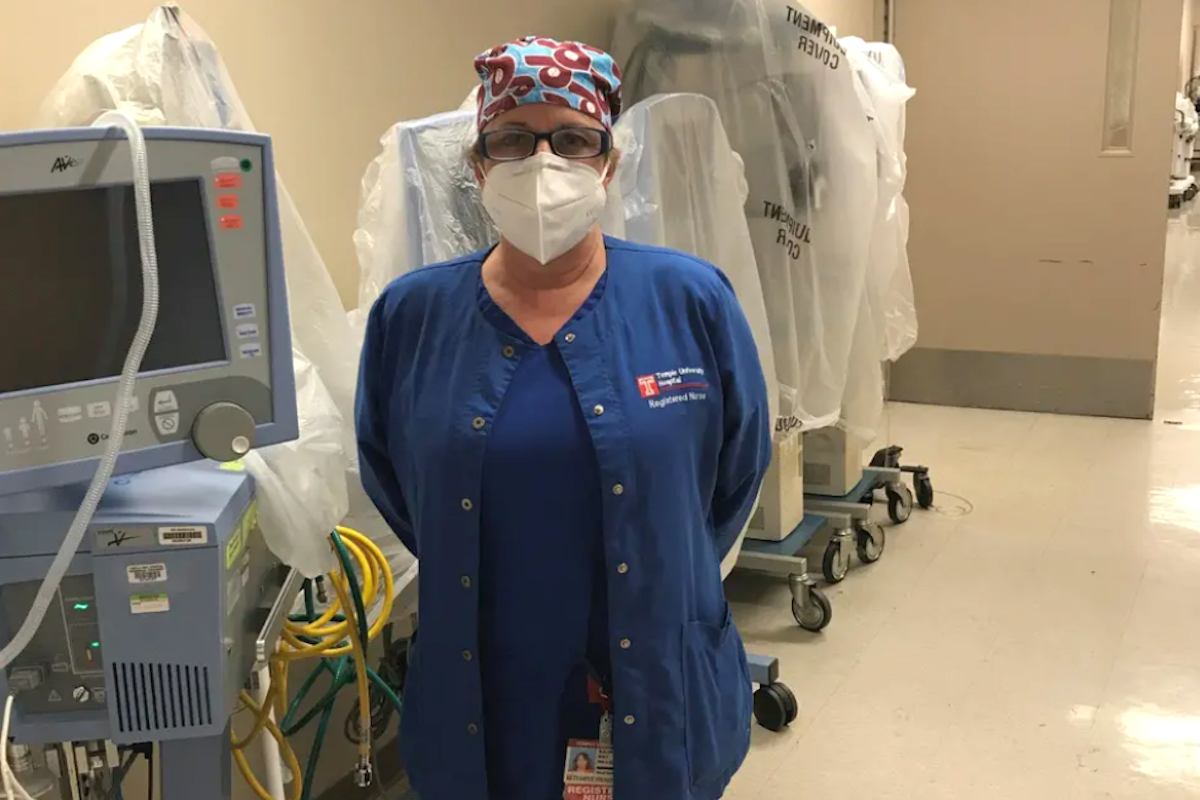

Maureen May, a registered nurse for 37 years, works in the neonatal intensive care unit at Temple University Hospital in addition to her duties as president of the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals (PASNAP). The union has 27 locals and represents more than 8,500 nurses and health care professionals across the state.

At Temple University Hospital, there is only language in the contract that supports staffing grids, May said. “The hospital has always had their staffing grids in order to determine … the amount of nurses that the nursing resource office was going to provide the floors with, and they wouldn’t really give those up,” she said. “For years, we had fought to just even see what they were thinking was the right number of nurses.”

Temple currently uses a system where nurses fill out short-staffing forms when the grids are inadequate. But May said she’s seen hundreds of those forms come in over the past few months, meaning hundreds of days where nurses felt they were short-staffed.

Angela Cleghorn, an ICU nurse at Temple University Hospital’s Jeanes Campus in Northeast Philadelphia, is president of Jeanes Hospital Nurses United. She’s been on the job for 17 years.

“Like, we’re not manufacturing car parts here. We’re not working on a factory line, not that I’m dismissing those jobs or diminishing them, but we’re taking care of human life,” Cleghorn said.

At Jeanes, unit-specific staffing grids are set by management. Cleghorn said the grids don’t account for acuity, though — how complex or severe a patient’s case is. “So, for example, if we have 16 patients, they’ll give us what, eight nurses for 16. However, there might be multiple 1-to-1s on the unit, there might be a 2-to-1,” Cleghorn said.

Temple Health officials did not immediately respond to a request for an interview.

At Suburban Community Hospital in Norristown, nurses have an agreed-upon staffing grid with hospital administrators. Yet according to Shannan Giambrone, an ICU nurse who is president of the PASNAP local there, that has not stopped management from bending the rules and encroaching upon agreements.

“They can’t arbitrarily change our numbers. But the problem with our contract and every other contract in the state, no matter how good it is, is holding them to it. So they break the rule. And then we file a grievance,” Giambrone said.

A spokeswoman at Prime Healthcare, which owns Suburban Community as well as Roxborough Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia and Lower Bucks County Hospital in Bucks County, said in a statement to WHYY News that “early on, it was evident we were dealing not only with an increased patient need, but also new medical practices that changed as our knowledge of the virus continued to evolve. The increased patient load led to added difficulties and pressure on our frontline staff, as has been experienced at hospitals throughout the nation.”

“In the face of these difficulties, Suburban Community Hospital took action to reinforce our nursing staff by offering staffing incentives and contracting with local nursing staffing agencies,” the spokeswoman said. “We continue to assess staffing volumes by patient and unit needs. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, proper planning ensured adequate patient safety and care without furloughing employees. We continue to be fully staffed with medical professionals who are available to treat all patients who present to our doors, we are monitoring our census closely, and we have a backup plan if the census once again increases.”

Though most unions negotiating new contracts in 2020 fell short of their goals regarding staffing grids, there were rare success stories.

In Delaware County, it took months of virtual negotiations, but 1,400 nurses and health care professionals reached a deal with the Crozer Health System that included pay increases, a program to reduce nurse burnout — and staffing grids with more specific employee input at several of their hospitals.

“This is the first time I think anybody’s gotten safe staffing grids in a contract in the state of Pennsylvania,” said Sharon Byrnes, an ICU nurse at Crozer Health’s Delaware County Memorial Hospital.

Peggy Malone, a nurse in the detox unit at Crozer Chester Medical Center and vice president of the Crozer Chester Nurses Association, said the grids “will allow for the patient to receive better care. It’ll allow for the nurses to be able to give better care, which I think will definitely help with the retention of nurses.”

In a statement to WHYY News, Crozer Health explained why it agreed to adding staffing grids in the new contract.

“Crozer Health is committed to open and honest communication with our employees. When the nurses’ union asked us to include our staffing guidelines in their contract, we did so in an effort to be transparent and to ensure our overall commitment to patient safety and patient satisfaction,” the statement said.

Despite the commitment, Crozer does not currently have enough nurses to activate the new grids and is trying to recruit them to fulfill staffing needs, the health system said.

The legislative approach

Although many union locals were unable to secure staffing ratios in their new contracts, they were simultaneously working on a more ambitious plan: legislation.

Mandated nurse-to-patient ratios are among the most controversial topics in the world of health care.

In 1999, California approved a landmark measure, Assembly Bill 394, becoming the first state to establish by law minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in hospitals. More than 20 years later, California remains the only state to have staffing ratio laws on the books.

Last month, several Pennsylvania nurses organizations — PASNAP, Service Employees International Union Healthcare Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania State Nurses Association, and Nurses of Pennsylvania — backed state legislators introducing the Patient Safety Act (HB 106 and SB 240). The legislation seeks to establish minimum nurse-to-patient ratios, whistleblower protections, and safe-staffing committees.

A similar State Senate measure in 2019 failed to gain traction. PASNAP president May thinks things will be different this time around.

“And the exciting part is that we’ve got more co-sponsors in the Senate and in the House … than we’ve ever had. This is bipartisan,” she said.

State Sen. Maria Collett, a Democrat, and State Rep. Thomas Mehaffie, a Republican, are the prime sponsors of the bills, which are almost identical.

“I’ll take either bill. I’m very happy to say, if we can get one of these passed, I am going to be elated that we can get this done,” Mehaffie said during a virtual press conference.

Despite growing support, the Patient Safety Act isn’t without its critics.

Robert Shipp, a registered nurse and vice president of population health and clinical affairs for the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania, said that although the group is still reviewing the legislation, it is opposing the measures

“Nursing, as we know, is one of the most honorable and trusted professions. And, you know, they provide critical care, that’s very vital for patients,” Shipp said. “And they don’t treat their patients just as a number. But this legislation kind of looks to do that.”

Shipp said he understands some of the core principles behind the legislation, but cautioned against looking for a one-size-fits-all approach.

“I understand that there’s some pieces of this legislation that look to spell out specific aspects. But if we look, and really the pandemic sort of even really highlighted this, there are different challenges across the commonwealth,” Shipp said. The group wants hospitals to be able to maintain flexibility.

When asked whether the association had any alternatives to addressing nurse burnout, Shipp pointed to its online Resiliency Toolkit, which it disseminates to its network of hospitals and health care systems across the state.

The toolkit includes an overview of the impact that staff burnout has on both patient care and health care workers. It also contains tips on identifying stress and a checklist managers can use to build resilience and manage stress.

In 2020, experiencing burnout from the flood of extremely ill COVID-19 patients and heavy workloads, many nurses walked away from the profession. Longtime nurses opted for early retirement, and many nurses fresh out of school chose to work outside of hospitals.

“A lot of them don’t want anything to do with hospital nursing, because they can go other places, and do other things, and they don’t have to work 24/7,” said Sharon Byrnes, from Delaware County Memorial Hospital.

Nurse shortages have been among the biggest threats facing the health care industry during the pandemic. But nurse retention was a growing issue even before 2020.

“We cannot retain our nurses. And that is something that we have been talking to our administration about for years,” said Chelsea Rabena, vice president of Einstein Nurses United.

Crozer Health’s hospitals will use new contract salary scales, that make their nurses among the highest paid in the state, as a recruiting tool. The same cannot be said of other hospitals.

“I don’t know what Einstein has to do, but they have to figure something out,” Rabena said. “Because if you don’t have nurses, I don’t know who’s gonna run the hospital.”

Nursing has never been this difficult, said Malone, from Crozer Chester Medical Center. A nurse mentorship program will go a long way toward keeping nurses working in hospitals, she said.

One year into the pandemic, the health care industry has lost nurses to both the coronavirus itself and the stressors of working to conquer it. Nurses, both new and old, had to learn on the fly.

The nurses interviewed for this article had mixed feelings about whether the pandemic and being in the public’s eye influenced contract negotiations in 2020. On the surface, staffing grids may seem like a labor issue, but the nurses said it is much more than that.

“We’re looking for better conditions in our workplace … but really, we’re looking for better conditions because we want better for the patient,” Giambrone said. “We’re fighting for a public health safety issue, not for better workplace policies.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)