Princeton Art Museum offers a rare look at some its hidden watercolor paintings

There’s something about watercolor painting that seems a perfect fit for a summer exhibition – perhaps the watery way the paint absorbs into the paper is as cooling as a dip in a refreshing lake.

Even though most of us played with water-based paint in school, it is nonetheless intriguing to learn that “watercolor paint is a finely ground pigment suspended in an aqueous solution of gum Arabic, made from the sap of the acacia tree.” This all comes to life in Painting on Paper: American Watercolors at Princeton, on view through Aug. 30 at the Princeton University Art Museum.

Watercolor gets its luminosity from the light reflected from the white paper beneath the layers of wash. Gouache, watercolor’s close cousin, is actually watercolor paint with the addition of white paint or chalk to give it opacity. Because of the way it runs and bleeds, watercolor is challenging for an artist to control. At the same time these qualities allow a freedom of expression.

Princeton rarely exhibits its watercolor holdings because of the paintings’ sensitivity to light. Assembled over nearly a century, the collection provides a comprehensive overview of American painting and shows the evolution of trends and themes in American art.

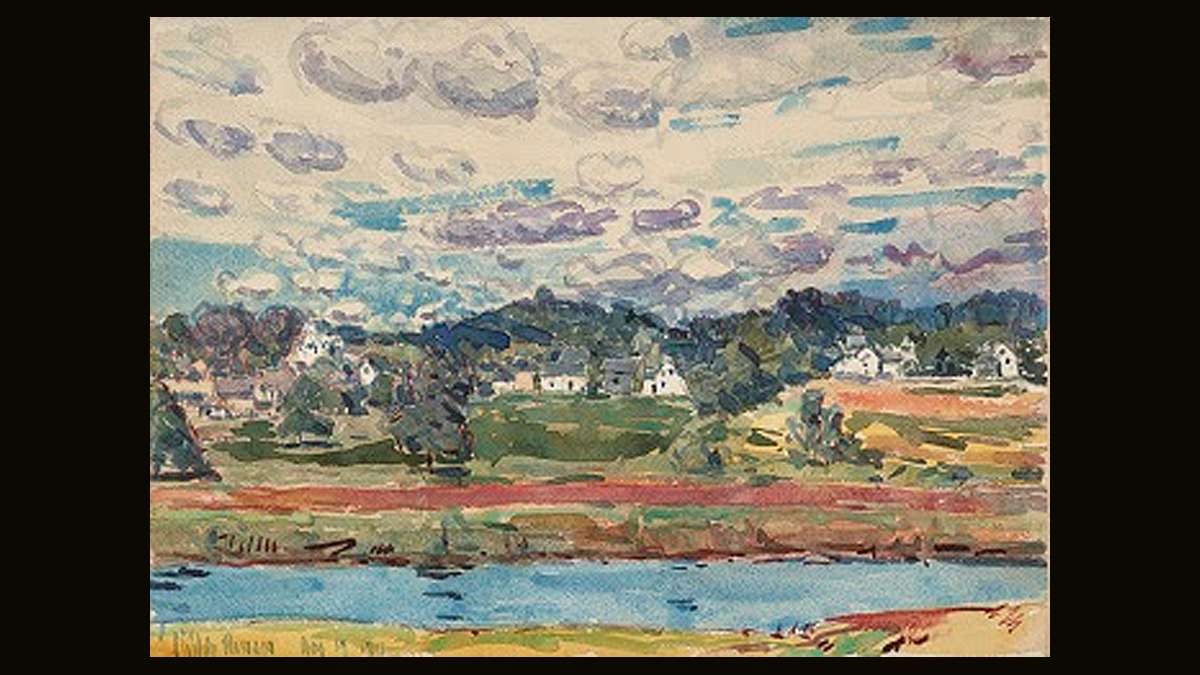

Watercolor flowered in 18th-century England, simultaneous to an appreciation of nature and the physical world. Americans took it up in increasing numbers in the 19th-century – it was portable and could be rapidly executed. Landscapes were intended to be literal depictions of localities in order to provide information about the growth of the nation’s rural, urban and frontier lands.

An early 19th-century work by an unknown artist shows a view of the Hudson from the West, using pen and ink to outline the buildings and roofs of a village in the distance, as three women kneel under a tree in the foreground. Another painting from a similar period shows a group of people in their feathered hats and fur-trimmed finery enjoying an afternoon in the garden of a cemetery. This was before large planned parks were established, and the subjects have found a place to interact with nature, albeit in a drawing room arrangement of tables and chairs.

These early watercolors in a pre-photography era were used to record the likenesses of people. In the mid to late 1800s, watercolorists painted landscapes, some even photorealistic, although the artist could play with colors to create drama in a sky, snow drifts or the vista of a mountain on a fall day.

Following the Civil War, watercolor was practiced more widely here than any other country. After the publication of “On the Origin of the Species” (1859), watercolorists adapted a more personal approach, turning inward. Charles Burchfield projected internal states into his landscapes. Milkweeds seem to take on human qualities.

Artists such as Winslow Homer concentrated on the figure: women holding fans or parasols, sewing. In the summer of 1880, Homer was painting seascapes off of Gloucester, Mass., but then like other American artists, he traveled to Europe where a period of study was deemed part of an artist’s education. In England Homer spent two years painting the sea.

Some American artists, such as Childe Hassam, adopted a style similar to French Impressionism, using watercolor, and Ashcan School artists like William Glackens and Post Impressionist Maurice Prendergast all used watercolor. Some of those who gathered around photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz, such as Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove and John Marin, used watercolor as their primary medium. Modernist Edward Hopper could evoke beauty in loneliness and despair in watercolor just as he did in oil.

Watercolor was also a favorite for artists who made illustrations for newspapers – Walter Harrison Cady, Adolph Arthur Dehn, Glenn O. Coleman and William Gropper. Ben Shahn executed his series “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” in watercolor, creating the effect of an eye-witness sketch (although he worked from a press photo, shown here).

The exhibition ends with works made in the late 20th century by Andrew Wyeth and Jacob Lawrence, abstract artists Alexander Calder and Adolph Gottleib, and Richard Diebenkorn, who turned from abstract to figurative painting. Claes Oldenburg’s painting of an oozing slice of blueberry pie and melting ice cream serves as a metaphor for the medium.

Painting on Paper: American Watercolors at Princeton, on view through Aug. 30 at the Princeton University Art Museum.

________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.