Water: a crucial challenge

Oct. 21

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

(This is the eighth in a series of stories examining the infrastructure projects and challenges raised in the Civic Vision and Action Plan for the Central Delaware. This article looks at the issues involved in creating new water infrastructure and sustaining and improving what already exists.)

Previous stories:

Infrastructure overview

Parks and green space

SEPTA funding

Grappling with I-95

Center City Commuter Connection

The Street Grid

The role rail plays

The goal of the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware is to reconnect the city and its residents to the river’s edge. So on one hand it’s about making the best use of the riverfront land. On the other hand, it’s about finding the best ways to use and protect the water.

But in the aging, urban environment of Philadelphia, the combined sewer and storm water collections systems that serve the city are already overwhelmed each time there is a heavy rain. It’s evident by the overflow from the century-old pipes – operating as originally designed at a time in our history when environmental impacts were less understood – that contribute to the pollution of the rivers and remaining streams. The proposals for the Central Delaware would result in an eventual expansion of Center City by 30 percent along the river, increasing development and demand proportionately for this overburdened – by today’s standards – collection system.

To meet that challenge, a variety of approaches are being planned and some are already under way in other parts of the city.

There will be extensions of the traditional gray infrastructure – the underground pipes – that carry water to homes and businesses and move sewage away from the buildings.

There will also be green infrastructure – in the form of street trees and plantings, green roofs and rain gardens – to reduce and manage the amount of storm water runoff.

And there will be a renewed focus on blue infrastructure – the waterways themselves – and the best ways to restore, clean and appreciate them.

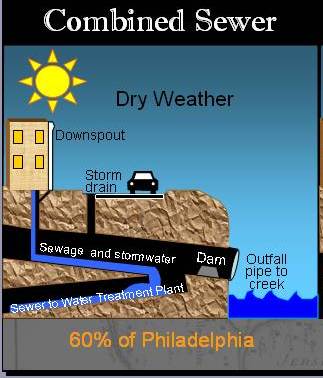

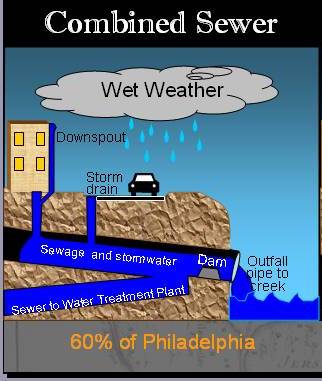

The Combined System

The Philadelphia Water Department has three purposes: to provide drinking water, to move and treat sewage, and to manage storm water. In Center City, as in older American cities, the wastewater and storm water are typically conveyed in a combined system. “The problem is, when it rains, the system tends to overflow,” said Howard Neukrug, director of the department’s Office of Watersheds.

In a combined system, sanitary waste, which uses a small fraction of the capacity of a combined sewer, is carried to a treatment facility. A small amount of rainfall can usually be accommodated by the interceptor sewer, which delivers the first flush of the rainstorm and sewage to the wastewater treatment plant. But as soon as the rain intensifies, the interceptor sewer fills up and the sewage tainted water flows out to the river, explained Mami Hara, a principal at WRT, the design firm that is working with the Water Department to articulate alternatives to the traditional systems.

“There are many ways the system will be changed in coming years,” Hara said. “You have to use many different approaches. So some re-piping will probably be necessary just given the sheer volume and urgency of the issue. When you think about the degree of impervious cover in our city and you multiply that area by even one inch of rainfall, the volume the system must handle is just extraordinary.”

About 95 percent of the flow into the waterways from the large outfall pipes is storm water, which carries trash and pollutants from the streets and sidewalks, and 5 percent is sewage. “Although these contaminants are diluted by the much large storm water volumes, the goal is to prevent these overflows from occurring under most storm conditions.,” Neukrug said. “During a storm, a river or stream is flowing full, and contains pollutants discharged by pipes or picked up by stormwater runoff. That is why we also need to tackle these issues on a watershed basis, as Philadelphia is always the downstream community.”

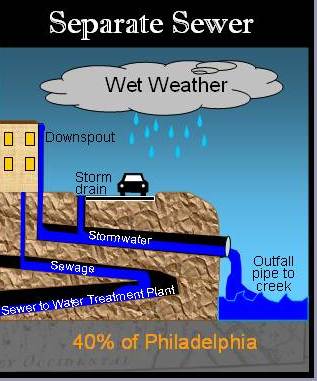

The Office of Watersheds, therefore, looks at how to keep the water out of the sewer in the first place. And if that can’t be done, it looks at that gray infrastructure and considers the alternatives. “Do we build tunnels? Do we build tanks? Do we increase the size of the sewers? Do we separate the system so that the storm water is still dealt with through infrastructure, but separately from the sewage?” Neukrug said.

“So we’re dealing with this through land-based or infrastructure-based solutions.”

The Gray Way

The current system along the Delaware consists of a large, underground sewer pipe that runs parallel to the river and intercepts all the sewer lines, which once carried wastewater and storm water straight out to the river.

Aramingo Canal

Those original systems were developed in the mid- to late-1800s, when waste was dumped directly into the city’s small streams. Dozens of creeks wound through and down the city’s natural slope toward the Delaware. “The streams became less and less valuable to the city because they became more and more polluted, and they became places that didn’t allow for easy transit over them by trolley or horse. So they became places to collect that stream into a sewer and cover it over,” Neukrug said.

“Over time, our infrastructure has significantly expanded,” he said. There are now 3,000 miles of sewers. There are combined sewer outfalls, where the pipes discharge into the river, in addition to 454 storm water outfalls in parts of the city where separate lines carry only rainwater.

Major gray infrastructure projects continue throughout Philadelphia, including a three-million-gallon tank being built in Manayunk to reduce overflows to the Schuylkill River and a $40 million storm water tunnel system nearly

finished under Kelly Drive in East Falls.

New infrastructure is a very costly and disruptive approach, Neukrug said, “but it’s the approach that has always been used. It’s how we’ve dealt with everything to date. Our philosophy has been to move the water and sewage away from the people as quickly as possible. That is the philosophy that has gotten not just Philadelphia, not just the United States, but the whole world in the kind of water situation that we’re in now.” The importation of American sewer system technology has led to enormous sanitation problems in developing nations, he added.

“At the same time, you look at this system and wonder how sustainable it is move the water away from folks, away from where they live. So part of our philosophy is to bring that back around and to make Philadelphia and the region more sustainable. And part of that is to use and re-use water where it lands, or as close to it as possible.

“So we keep getting back to the land-based program, and that’s a sustainable, green approach for the future,” he said.

It is also “one of the hardest things for us to do. It’s very easy to build a pipe and move water away. What’s a lot harder to do is to mimic nature in an urban setting, and infiltrate water back into the ground water system. … Now we’re trying to design ways to make it easier, and make sure it makes sense.”

The Green Route

The PennPraxis plan points out opportunities for land-based storm water management at the most sensible sites along the Central Delaware, what Micale of WRT calls the “historic hydrology of the water’s edge.”

The Civic Vision foresees storm water solutions wherever there are low lying areas through which the creeks once ran and at each riverfront park that was once part of that creek system. Restoration of those sites would allow absorption, storage and filtration of storm water through rain gardens and other eco-technology.

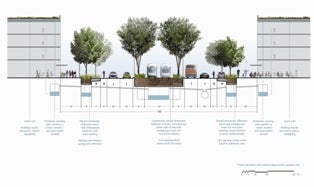

The proposed urban boulevard along the river could be landscaped with trees growing in trenches over underground cisterns, curb openings that carry runoff to infiltration zones, pervious paving and green-roofed

buildings.

Illustration from Civic Vision, page 89

A particular focus for green solutions in the PennPraxis plan is the I-95 Girard Avenue Interchange, which is being redesigned and reconstructed by PennDOT. “At the interchange, the idea is to mitigate the impact of the highway in place,” Micale said. Rather than allowing storm water runoff to continue under the current systems and regulations, “we’re saying if they’re going to redesign it, why go with the status quo?”

The Central Delaware plan redirects the runoff into rain gardens that are part of a recreational resource at the base of the interchange. The new green space would include trails for running and biking below the highway on land that now is mainly used for parking.

Many of the storm water management techniques incorporated in the Civic Vision are also being proposed for GreenPlan, the citywide sustainability program that is expected to be introduced in January. WRT is helping the engineers at the Water Department and from CDM, the consulting and construction firm, to develop and articulate the possibilities for green streets throughout Philadelphia, including the proposed street grid on the waterfront.

The WRT drawings show large streets with greened medians, and medium-sized streets with tree-lined sidewalks. Below the surface of the streets are continuous trench systems that can store and absorb much of the water that would otherwise go into drains and the sewer system.

Dickinson Street before / WRT image

Dickinson Street after / WRT image

“We also have a lot of really narrow streets in the city,” Hara noted, “and sometimes there are so many utility expressions along the sidewalk that it’s impossible to plant a significant number of trees. Every single foot might have some kind of water or gas main. But that doesn’t mean it precludes some kind of greening that can bring storm water management enhancements.”

She pulls up drawings of continuous beds of gravel below the parking lanes and bump-outs which can provide storage capacity for storm water. “Here engineers originated the idea of vine-covered poles, using plants that can take up that water.”

The illustrations show not only the opportunities for storm water management, but also the “other values, such as traffic calming to the intersections, the high potential for aesthetic value, and all the other values that trees bring,” Hara said.

Other cities have been utilizing water runoff techniques for years. Portland, Ore., and Seattle are often cited, and Hara noted that Chicago has a Green Alleys program under way. Philadelphia has begun using land-based, storm water management at a variety of public sites, including schoolyards and recreation centers, but it is “still in the pilot phase.”

Any new streets planned for the city, including those on the waterfront, “should be green streets,” she said, adding that “retrofits are possible for a considerable amount of streets, too.”

Schoolyard before / WRT

Schoolyard after /WRT

Land-based programs to stem the storm water overflow is the Water Department’s favored approach, Neukrug said, “because it is based on keeping the water out of the sewer, and we like finding some secondary benefits to everything that we do. Whether it’s planting trees, creating green streets, or greening school yards.”

Examples of innovative storm water control include Cliveden Park in East Mount Airy, a project designed in partnership with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society in which new inlets were dug to direct street runoff down a series of rocks, forming a gentle waterfall that flows into a rain garden in the park. Street runoff will be redirected and infiltrated into a green feature instead of into the city sewers in projects currently under way at the Liberty Lands neighborhood park in Northern Liberties and at Columbus Park in South Philadelphia. “If we could do that all over the city, it would be great,” Neukrug said.

The Water Department also poured its first porous concrete sidewalk at the Waterview Recreation Center in Mount Airy. “That’s really cool – one of my favorite projects,” Neukrug continued, “because unlike many of the other projects, it doesn’t look like anything. It’s a green project, but it doesn’t even look green. It’s just a concrete sidewalk. But a porous concrete mix uses uses larger rocks and less fine materials, allowing the voids in the concrete to take in water. It can handle an incredible amount of rainwater. And it’s so basic.

“When we started this project we thought about how to mimic nature. We were very clumsy at it. All of these things that we’re doing are not really all that well designed yet, and probably won’t be for another five years. How to do a rain garden, a rain barrel, a green roof – all of these things right now are a little clunky, but much less clunky than five years ago. As we move forward, we’re going to find simpler and simpler designs that are less expensive and require less maintenance,” he explained. “As engineers and landscape architects think about how to rebuild and do these things, we have to step back and realize simplicity really does work.”

New development regulations that require more stringent stormwater management have been implemented by the Water Department. And a new method for calculating property stormwater fees is being developed to would “bring the customer base to a true cost of service fee – so that now we’re charging people who have impervious cover more for us to deal with their storm water than we do people who have more green sites.

“There are a number of incentive programs and green initiatives that we’re hoping to put in place with the city’s sustainability programs,” Neukrug said. “Energy management, reducing the heat-island effect, reducing storm water – they all come together under the programs we’re hoping will take shape over the next couple of years.”

Washington Ave. before / WRT

Washington Ave. after / WRT

Go Blue

The third piece of the Watershed Office strategy is its waterways program.

The federal Clean Water Act of 1977 turned everyone’s attention to point source pollution – the discharge points into the rivers and oceans. “And that’s what the Philadelphia Water Department became very good at, which is protecting our rivers and streams from our point sources,” Neukrug said.

Residents, however, want attention not only to discharge points, but also to the greater environment. “It’s not the pipe; it’s what the pipe is doing to everything else,” Neukrug said. “So we’ve opened our eyes to the rest of the water environment.”

The Water Department’s five goals for its waterways, including the Delaware, are that they be “fishable, swimmable, safe, attractive and accessible.”

“Now we’re looking not only at land-based solutions to keep water our of the sewer and infrastructure solutions to hold sewage back from the river, but we’re also looking at the river itself and figuring out what we can do to return them to something that is usable for recreation and valuable to the city for development and eco-tourism.”

The Office of Watersheds is exploring methods of wetlands mitigation, creation of new wetlands and ponds, daylighting streams, balancing flows, and “rebuilding every mile of stream bank that’s left in Philadelphia.”

Neukrug’s office is also working on bringing the creeks back into equilibrium. The creeks start upstream, in the overdeveloped suburbs. Their flow is typically very low, and when it rains the flows are very high. The low flow is bad for the fish and has an increased concentration of pollutants. “We’re trying to rebalance the flow and redesign the creek to handle the flow when floods happen.”

Working Well With Others

Tackling the creek sources upstream means working with the suburban municipalities, in addition to the city government and other agencies and organizations. So the fourth part of the Water Department’s storm water program is about partnerships.

“We are working with PennPraxis, the Schuylkill River Development Corporation, and others to understand how we can design our infrastructures and our green programs to support visions and plans that are out there,” Neukrug said. “We’re very involved with these plans because we’re trying to understand how our philosophy and our needs for our land-based and waterway programs best fit into others’ plans.”

At the same time, current plans for new infrastructure must coincide with “the needs of tomorrow, like those offered in the PennPraxis plan,” he said. “The problem is, we’re still several years away from a citywide vision of what we want to be. … The bottom line of what we’re doing here is that we’re going to have to spend a lot of money on water,” possibly billions, Neukrug said.

Much of the funding will come from water and sewer revenue, which means it’s important to pick projects that have a visible result for the ratepayers. “Seeing additional recreational opportunities on the waterfront is important; seeing economic development in the city is important.”

Pier 70 possibilities

To open the Delaware to recreation, Neukrug sees access points along the branches of that “historic hydrology” leading to the river. The finger piers also present opportunities to bring people to the water, and the Vision Plan has suggested ways to re-use the land and the water between them. “We can start combining those ideas with our ideas for some of the outfalls at those spots. We fill them, perhaps, then extend the pipe to the river, and use them for storm water storage. “There are lots of things you can do.” There are also other “interesting ways of funding these things,” Neukrug said. The Office of Watersheds has created an index of Watershed Registry Projects, a new resource for developers. “As development occurs on the waterfront, there’s an incredible need by these developers to mitigate somewhere else for the wetlands that they’re destroying, or the water that they’re taking, or the shadows they’re casting over fish habitat.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Army Corps of Engineers all require that the developer must then taken mitigation measures elsewhere in the region. The Watershed Registry is a list of sites where that mitigation is needed.

“There is a combination of needs up and down the waterfront, such as access for recreation, protection of habitat, and wetlands creation,” Neukrug said. “The PennPraxis plan accounts for these needs, and has the same values as our program. As development occurs along the waterfront, ecological restoration is going to be needed.

“But the Central Delaware is going to have only so many wetlands sites available. So what we’re creating is a wetland mitigation registry which will facilitate development while ensuring that the city’s precious water resources are preserved. Sites are being identified throughout the region,including many in Fairmount Park, another partner of the Office of Watersheds.”

Hara, of WRT, agrees that the approaches to storm water management on the Central Delaware must go beyond the Central Delaware.

“We have a long waterfront, and each section poses a whole series of point source and non-point source pollution. They present all sorts of technical challenges. So a really comprehensive understanding of all the technical issues will inform what are the best uses and opportunities.”

Storm water management is “both local and global. It occurs at many scales,” she said. “The challenge is to develop design guidelines and codes and regulations that support that positive relationship between those environmental concerns and our development desires.”

Contact the reporter at ajaffe@mac.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.