Want to move to a better neighborhood? In Philly, help is on the way.

As of this month, families will be able to be able to use vouchers that can be stretched to cover higher rent in select deemed higher opportunity zones by the PHA.

Myia Hurst in her Roxborough home. (Photo courtesy of Philadelphia Housing Authority)

Myia Hurst lived in a constant state of anxiety for five years. The mother of two went to bed with the sounds of gunshots ringing out below their apartment near 60th and Market Streets in West Philadelphia. Worries about violence woke her up early, before long days of studying for a bachelors degree in psychology at Drexel University.

“I was always worried that one of my children could be hurt or I could be hurt,” she recalls.

Life changed for the better in 2016 when Hurst was able to move across the city to a more economically diverse part of Philadelphia where she hadn’t before imagined living but found herself happy. “I live in Roxborough because it’s a safer area,” says Hurst, who has since earned a masters degree in public health from West Chester University and found full-time employment. “No one is shooting someone on the corner, you aren’t getting off the bus, and someone is robbing you.”

It was a move made possible by a Philadelphia Housing Authority initiative aimed at helping their tenants find housing outside of the high-poverty neighborhoods where most households that receive housing assistance are concentrated. Two years after this initial experiment, PHA this month instituted reforms to its Housing Choice Voucher program that will allow even more families to make the same leap into safer parts of the city where incomes are higher and access to better schools, jobs and transportation options more plentiful.

“This is a way for PHA to proactively further fair housing by making housing more accessible in higher rent neighborhoods,” says Kelvin Jeremiah, the housing authority’s president. “We believe that’s a good thing for the city, for our families, and in the end it deconcentrates poverty.”

In Hurst’s case, the move to Roxborough brought her and her children into a community with a poverty rate of 11 percent — a 20 percentage point drop from the 33 percent rate in her old neighborhood, according to PHA data.

Th reform to the voucher program, colloquially known as Section 8, gives PHA and its counterparts across the region the flexibility to set the value of vouchers based on average market rents on a zip code level.

Up until now, the formula determining rent values was based on prices across the metropolitan region, or in the case of Philly, the city. That meant a voucher was worth the same amount of money in North Philadelphia or Center City, locking subsidized tenants out of higher-rent areas and allowing landlords in less desirable neighborhoods to charge more than they might otherwise.

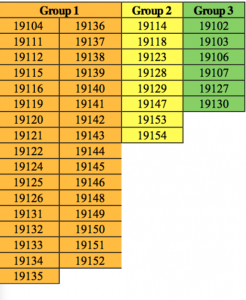

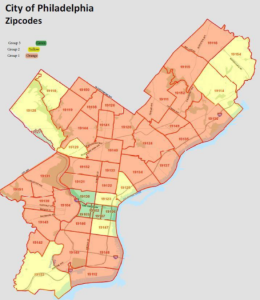

But as of this month, families will be able to be able to use vouchers that can be stretched to cover higher rent in select deemed higher opportunity zones by the PHA. The highest opportunity areas span just six zip codes; one in Fairmount, one in Manayunk, and the rest in Center City. In this tier, a voucher up to $1,098 could be used for a studio and $1,980 for a three-bedroom. Under PHA policy, voucher-assisted tenants can pay more out of pocket to cover higher rents.

The second tier covers eight zip codes that include neighborhoods in parts of the Far Northeast, Northern Liberties, Queen Village, and much of northwest Philadelphia outside Germantown. In these areas, the housing authority will cover up to $891 for a studio and $1,602 for a three bedroom. The 19123 section of Northern Liberties eligible for the mid-level subsidy was recently deemed one of the nation’s 10 fastest gentrifying zips.

The rest of the city, including another one of the nation’s fastest gentrifying zip codes — 19146 in Point Breeze, and other areas where rents are increasing — comprise the lowest opportunity tier, where $1,360 is the highest rent the housing authority can cover for a three-bedroom apartment, and $760 is the most for a studio.

Current leases set under the old voucher formulas won’t be affected by the new rules, so no landlords who currently have Section 8 tenants will experience a decrease in rent, and no tenant will experience an increase in rent.

EditDeleteThis PHA map shows voucher payment rates across the city, with group 1 ( green) at the highest tier and group 3 ( red) the lowest.

Under the reform, known as the Small Area Fair Market Rent rule, housing authorities in the rest of the metropolitan region will also have to alter their rental voucher formula, making it easier for Philadelphia renters to move to the suburbs.

The change is a win for Philadelphia renters and the PHA, which in the past tried to work with suburban housing authorities on a “mobility program” to get tenants into higher opportunity neighborhoods in the surrounding counties. But the deal fell apart and PHA instead just tried to give some voucher holders like Hurst greater choices within Philadelphia through counseling and working with landlords in higher opportunity areas. The new rule will make it harder to keep PHA voucher holders from using their subsidy in counties outside the city.

“One of the objections of the suburban housing authorities for not wanting to participate in the mobility program was the payment standard,” says Jeremiah. “With this model, it is something HUD is requiring us to do, to pay higher rent, which is good for those [moving] to places where rents are higher.”

The federal government created the Section 8 voucher program in the 1970s as an alternative to the traditional New Deal-era public housing program, which tended to reinforce racial segregation and concentrated poverty.

Vouchers could be used anywhere, even taken across state lines. But in actuality, people who participated in the program often ended up in the same low-income, and often racially segregated, neighborhoods as the project-based public housing.

The Small Area Fair Market Rent program has its origins in a 2014 lawsuit launched by Texas’s Inclusive Communities Project. The group sued the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) over the segregationist impact of a subsidy formula for the Dallas metropolitan area which was based on rental prices across twelve counties. They argued that Section 8 voucher holders in the region were disproportionately concentrated in low-income, highly segregated areas with poor access to employment.

Inclusive Communities and the feds settled the suit, and the zip code-based model was instituted in the Dallas area. Years later research showed it allowed far greater mobility across the region at no additional cost. A series of pilot programs in smaller housing authorities demonstrated similar results.

In 2016 Obama administration launched a rule requiring the Small Area Fair Market Rent policy to be adopted in 24 metropolitan regions, including Philadelphia, by the beginning of 2018. But last year, Ben Carson’s team at HUD tried to delay the rule requirements, arguing that more research into the issue was needed.

Although HUD’s move to delay was eventually thrown out in court, it did push back implementation from January 1, 2018, until this month. National representatives of the apartment and multi-family housing industries supported Carson, and the Pennsylvania Apartment Association East stands by their skepticism about the rule.

“Nobody is convinced that using zip codes will actually provide a valid real estate market,” says Christine Young-Gertz, government affairs director for the Pennsylvania Apartment Association East. “Everyone supports the idea of moving low-income households into as many neighborhoods as possible, but they don’t think the small area fair market rents has been vetted properly.”

The association did not offer any alternative formulas.

Hurst, however, sees possibility in the change. She says that she would have loved to move to a suburban area with better schools for her autistic son.“It’s important for people in Philadelphia to be able to move to the suburbs for the educational system,” says Hurst. “The amount of money per student is much higher there than what Philadelphia is able to give its students.”

But regardless of whether her fellow voucher holders decide to move to the suburbs or a different part of Philadelphia, Hurst is happy that more people will have the opportunity to move out of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. For her, the vouchers, and PHA’s mobility program, have proved a success: her years of nursing school have paid off, she is now employed full-time, and plans to leave the voucher program.

“Your home is your haven,” says Hurst. “Who wouldn’t want to come home to a better environment where you and your children feel comfortable. Anyone would want that.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.