Walter Wallace Jr.’s neighbors say bodycam footage reveals systemic problems — and they have solutions

After Philadelphia Police released bodycam footage of Walter Wallace Jr.’s shooting death, West Philadelphia residents have ideas for reform.

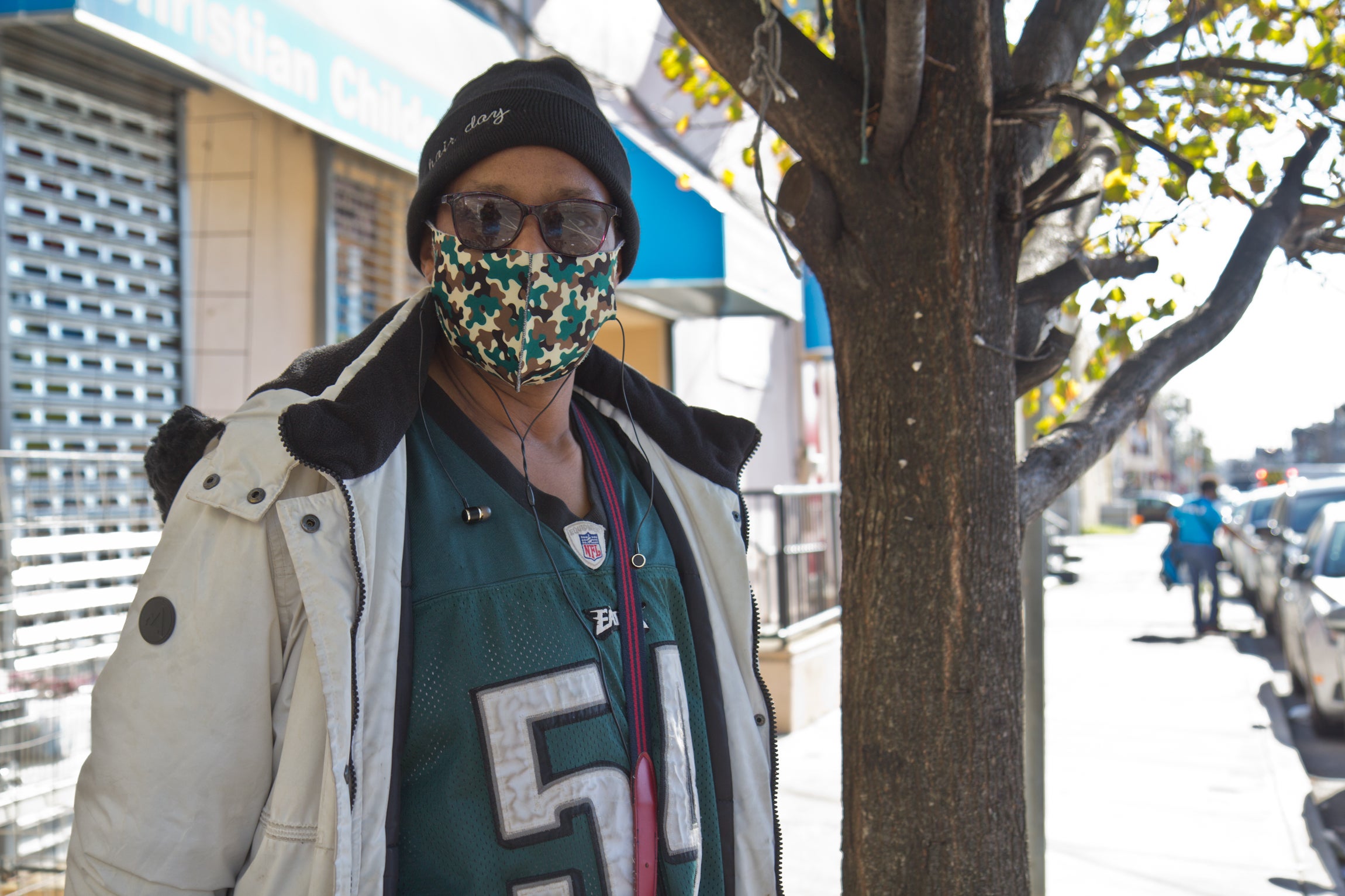

Lifelong West Philadelphia resident Sybil Jordan said racism in policing the community has been around for a long time. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

When Sibyl Jordan, 66, first heard the news of the Walter Wallace Jr. bodycam footage coming, she already had a laundry list of questions: Where were the paramedics? Where was the ambulance? Why were the officers so aggressive?

When the Philadelphia Police Department released the footage Wednesday evening, nine days after the fatal shooting that made international news and inspired protests across the city, it still didn’t answer any of her questions.

The video is the first bodycam footage ever released publicly by Philadelphia Police Department. Law enforcement also released audio from the 911 calls before police arrived. It shows that Wallace, a 27-year-old Black man experiencing a mental health crisis and carrying a knife, was not rushing at the officers when one told the other to “shoot him.” His knife was not raised at the time they shot him from several feet away. The fatal shots rang out just minutes after family members out on the street alerted the police to Wallace’s mental state.

“I don’t feel as though from what I’d seen that he was a threat,” Jordan said. “It was enough officers there to subdue him.”

Jordan, a grandmother who has lived her entire life in Cobbs Creek, the neighborhood where Wallace was killed, felt that it was an unnecessary use of force, but wasn’t surprised. She said nothing has changed when it comes to community and police relationships for as long as she can remember.

“[Police] need a substantial amount of training and not just once,” she said. “They need to be monitored and supervised at all times. And they need to have a refresher course every six months.”

Walking through Cobbs Creek one day after Philadelphia got its first glimpse of the wrenching footage of police shooting Wallace in front of neighbors and his mother, people were still bustling about like a normal day. When stopped and asked about the footage, most people’s faces either turned irritated or somber. A few said they didn’t watch it either because of work, the craziness of election week, or because they didn’t feel the need to see another video of a Black person being killed by the police.

But whether they watched the video or not, many had suggestions about how to fix systemic problems of violent over-policing they had long observed in the predominantly Black, working-class community.

Trainings must tackle racism

Jordan said she believes that officers tend to target Black neighborhoods within the city and not other whiter areas. Crime happens everywhere but she said she sees more police in her neighborhood.

In Wallace’s case, police were not responding to a call about a criminal action. In one of the 911 calls, a woman who identified herself as Wallace’s sister requested medics explaining that her brother was being violent toward her parents. No weapons were involved she said, but “my dad said he’s about to faint and my mom’s blood pressure is all the way up.”

Jordan said racism made her neighbors a target.

“Violence is all throughout the city,” she said. “We’re always going to be a target. Nothing has changed.”

The Cobbs Creek woman also thinks officers should make a point to get to know the neighbors. If officers don’t have that inclination, then the training that she proposes won’t amount to much.

“You can [give them] all the training in the world,” Jordan said. “But stop sending other [races] to our community that don’t want to know how we live, how we think, how we act, how we walk, or how we talk.”

Even with these ideas, she’s not optimistic about the future.

“I’m fearful for my two grandsons, I have nieces, I have nephews,” she said. “It’s not just about the gender, it’s about being Black.”

Involve mental-health professionals

John White, the CEO and president of The Consortium, a neighborhood-based mental health center, already knew that Walter Wallace Jr.’s death could have been avoided. But after seeing the video, he witnessed how unnecessary the use of force was.

“He had a four-inch pocket knife,” he said, describing the knife in a way that has not been confirmed by police. “A Taser would have sufficed. But they didn’t equip them. They didn’t provide the police officers the tools necessary to do their jobs.”

Although he emphasized that this incident could have happened anywhere, it still hit close to home. He grew up three blocks from where the shooting took place at 61st and Locust Streets. He felt the killing could have been prevented if police had reached out to mental health professionals.

The Consortium knew Wallace and his family as clients but when they made their fateful 911 calls, no one from the Police Department thought to connect with the neighborhood-based mental health center.

“That highlights the problem,” said White, formerly a state representative, Pennsylvania’s secretary of welfare, and a city councilmember. “The lack of coordination, lack of collaboration, and clearly a lack of communication.”

The video revealed that the officers did not take any steps to deescalate the situation before one officer tells another to shoot and the officer pulls the trigger.

“I don’t understand why you are able to put two police officers in a neighborhood where, in the event they feel threatened, they only have one way out: and that’s to use their gun,” White said.

The two officers who killed Wallace didn’t have more than three years of experience.

White mentioned that mental health professionals from The Consortium have intervened in 1,200 cases. Of those cases, only six resulted in arrests and none resulted in deaths, he said.

But race still plays a role.

“I think everything points to the fact there is a propensity for police to respond in a more violent manner when it comes to a situation involving Black men,” he said.

Yet White stressed that the police gunfire that took Wallace’s life could have happened anywhere in the city.

“This is not just about West Philadelphia,” he said. “This is a citywide problem. It can magnify itself at any time when you fail to provide the expertise necessary to resolve these situations.”

More screenings and more officers

Charlene Raglan, 49, lives nearby. She described feeling disgusted since she first heard about the death of Wallace last week. The video only exacerbated her feelings.

“They could have done something to avoid taking that man’s life,” she said.

She said she thinks officers should be better screened to determine if they have the mental capacity to be in high-intensity situations.

In her eyes, there’s a two-step solution: She wants more trained officers on the ground and to see those officers engage with the community in ways that help build trust and empathy, similar to Jordan’s idea.

“I think that would eliminate all this nonsense that’s going on,” she said.

She said she remembers a time when police would walk around the neighborhood and create relationships with her neighbors.

“I’m not saying they need to know everyone by name, but they should know who [the residents] are and their circumstances,” Raglan said. “They need to come and interact with us more.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.