Visionary Genius John A. Roebling and Sons Remembered at Roebling Museum

It’s not every bridge that gets a birthday cake, fireworks, and the happy birthday song delivered by the mayor of the city of New York. But the Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883, is not just any bridge.

This is part of a series from Ilene Dube of The Artful Blogger.

It’s not every bridge that gets a birthday cake, fireworks, and the happy birthday song delivered by the mayor of the city of New York. But the Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883, is not just any bridge.

John A. Roebling gave his life to build it, and his son Washington Roebling forfeited his health, developing “the bends” while working in the caissons. (His wife Emily, serving as liaison between the ailing Washington and the workers, helped assure the completion of the bridge, transmitting directions).

Heroes of the industrial age

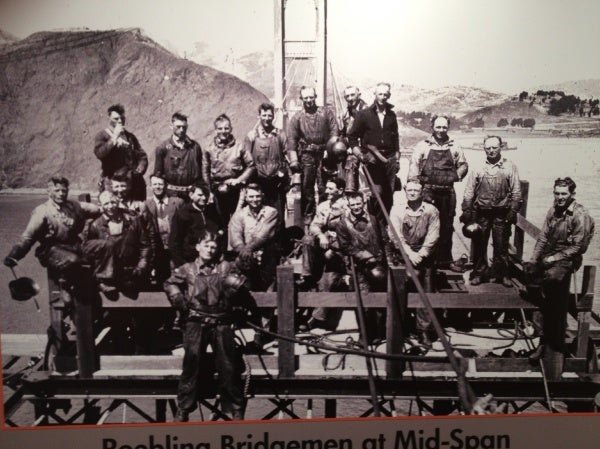

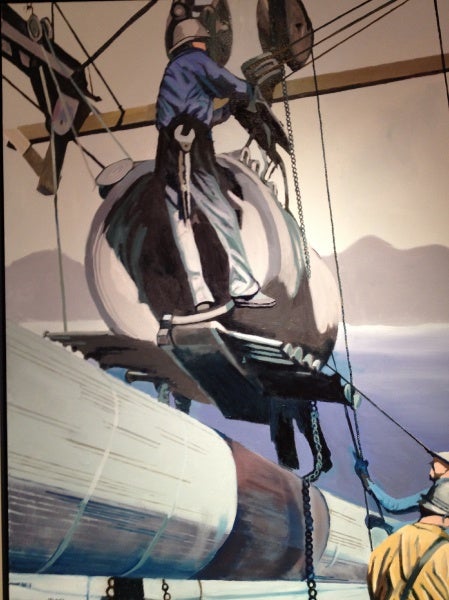

The Roeblings were heroes of America’s industrial age — Roebling and Sons were responsible for the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, the George Washington Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge — and their lives and accomplishments, as well as the ideal company town they built, are celebrated at the Roebling Museum in Roebling, N.J.

Today, Roebling is a stop on the RiverLine, between Camden and Trenton, but in 1904 it was a 150-acre farm along the Delaware, 13 miles south of the capital city. John Roebling’s son Charles bought the land to build a steel mill for the manufacturing of wire rope.

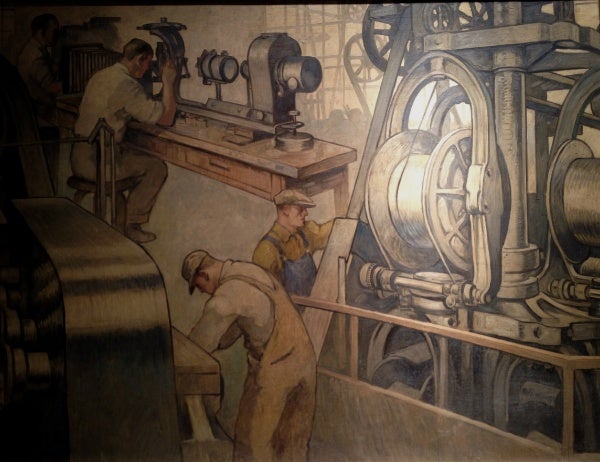

It’s not just bridges this family of engineers, architects and businessmen deserve our gratitude for. The Roebling Company’s wire rope lifts Otis elevators and stabilized the wings of the Wright Brothers’ first plane. Charles Lindbergh’s aircraft used Roebling wire, as did the stays in ladies’ corsets and even the Slinky. New York’s Empire State Building, Chrysler Building and Flat Iron Building, and even Paris’ Eiffel Tower use Roebling wire to pull their elevators.

Cable cars, ships, telephone and telegraph cables use the wire rope.

New urbanism

Kinkora Works opened in 1905, and Charles built the town to house the workers. It was modeled on Pullman, Chicago, a suburb designed by George Pullman for the George Pullman sleeping car company.

The homes were built of brick with slate roofs and chestnut trim in 15 distinct architectural types, and there was a community hall, a library, baseball and football fields and a recreation hall, as well as an inn.

The two- to seven-bedroom houses were allocated for different skill levels of workers. Single men slept in a boarding house, and semi-detached row houses were used for entry-level workers. Foremen and supervisors received more spacious Colonial or Tudor style dwellings.

There was an inn, a recreation center, school, ballpark, auditorium, bandstand, Boy Scout hut, boathouse, tennis courts, a general store and a tavern. “You can’t make a mollycoddle out of a mill man,” Charles Roebling remarked.

Social reformers believed if you gave spaces with trees and a park, lives would be improved and employers would benefit from less absenteeism and more productivity.

Most of the workers who came to live and work here were Eastern European immigrants recruited at Ellis Island. Accustomed to living in small villages, they saw the brick houses with indoor plumbing and thought they had landed in paradise, vying for the 3,000 jobs. At its peak, Kinkora Works employed 8,000, and inspired the motto “Trenton Makes, the World Takes.”

The Roeblings took care of their employees, and during the Depression they reduced the number of hours so there’d be enough work for everyone and they wouldn’t have to lay anyone off. Nevertheless, there were strikes for higher wages.

The grid of four-by-eight blocks is lined with London Plane trees, which provide a canopy and let light through. Main Street and Fifth Avenue are broad streets with central planted islands.

Eastern Europeans had a tradition of piling garbage in their backyard, and so the town manager encouraged upkeep by awarding prizes for the best gardens. A tradition of gardening grew here, with many families having their own vegetable patch. Each had a different fruit tree for sharing, and there were grape arbors from which residents made their own wine.

A system of alleys was designed behind the street for garbage collection as well as for merchants to make deliveries: chickens, milk, bread, even the horseradish grinder came through.

In a study conducted by Harvard architecture students, Roebling was cited as an example of the new urbanism, where everything is within walking distance, students can bike to school, row houses make efficient use of land, the alleys provide infrastructure, and everyone knows their community.

A lasting impression

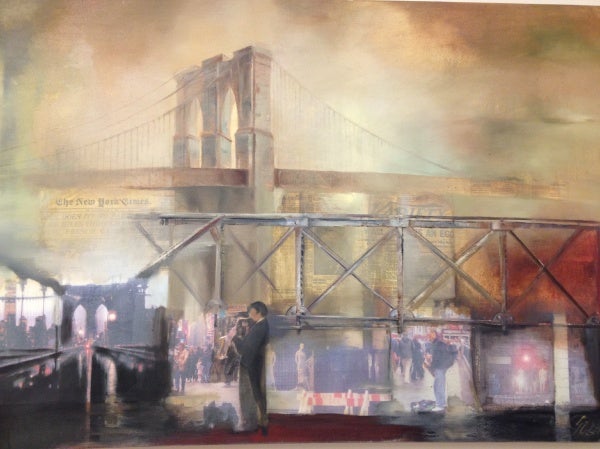

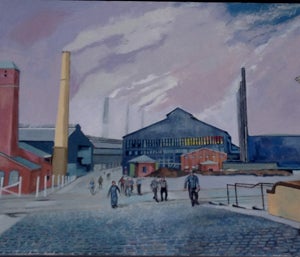

End of the shift, painted by Don Jones. (Ilene Dube/The Artful Blogger)

Unable to compete after World War II, and unwilling to take on debt to upgrade the plants, the Roeblings sold the business in 1953, and the plant shut down for good in 1974. The film shows workers lamenting the sad day. The flag was flown at half mast, and it looked as if the shift had just ended, they recollect.

In 1983, with new awareness of hazardous wastes, the area was designated a Superfund Cleanup Site, and work on the cleanup continues. The museum is built in the gatehouse, where workers came in every day to clock in and proceed to their work area. The 676 homes in the village are still intact, and a self-guided walking tour of the town is available from the museum.

The film recounts how John Roebling was born in Prussia in 1806 but came to the U.S. to make a better world. After a farming stint in Pennsylvania, he missed engineering, and when he saw how hemp ropes wore out, he began manufacturing wire rope on the farm. He built two suspension bridges in Pittsburgh, then a railroad bridge over the Niagara River, held up with wire cables, but it was his bridge in Cincinnati that became a model. He built his first factory in Trenton, a structure built so well it still stands today, available as a museum space.

Of the Brooklyn Bridge, Roebling wrote: “The completed work, when constructed in accordance with my designs, will not only be the greatest bridge in existence, but it will be the greatest engineering work of the continent, and of the age.” Anyone who has walked under its arches cannot disagree.

Employees took pride in working for the Roeblings. One 35-year employee said: “It was dirty rotten hot work, and I loved it.”

Current exhibitions: Calm Heroism: Washington A. Roebling II and the Titanic Disaster (Washington Roebling ll lost his life on the Titanic) and Spinning Gold, the Roebling Company and the History of the Golden Gate Bridge, both on view through Dec 31.

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.