An epic effort to breathe new life into once abandoned Philly cemetery [photos]

-

The cast of Beowulf/Grendel (from left) Ainye AnnaDora, Nia Benjamin, and Merri Roshoyan, rehearse in Mount Moriah Cemetery. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Mount Moriah covers 380 acres in Philadelphia and the bordering Borough of Yeadon, making it the largest cemetery in Pennsylvania. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Maura Krause directs Beowulf/Grendel at Mount Moriah Cemetery in West Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Merri Rashoyan plays the poet and several other characters in The Renegade Company's version of Beowulf to be performed at Mount Moriah Cemetery. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The cast of Beowulf/Grendel will lead their audience through the vast cemetery, separating and reconnecting. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Mount Moriah Cemetery has seen years of neglect. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

-

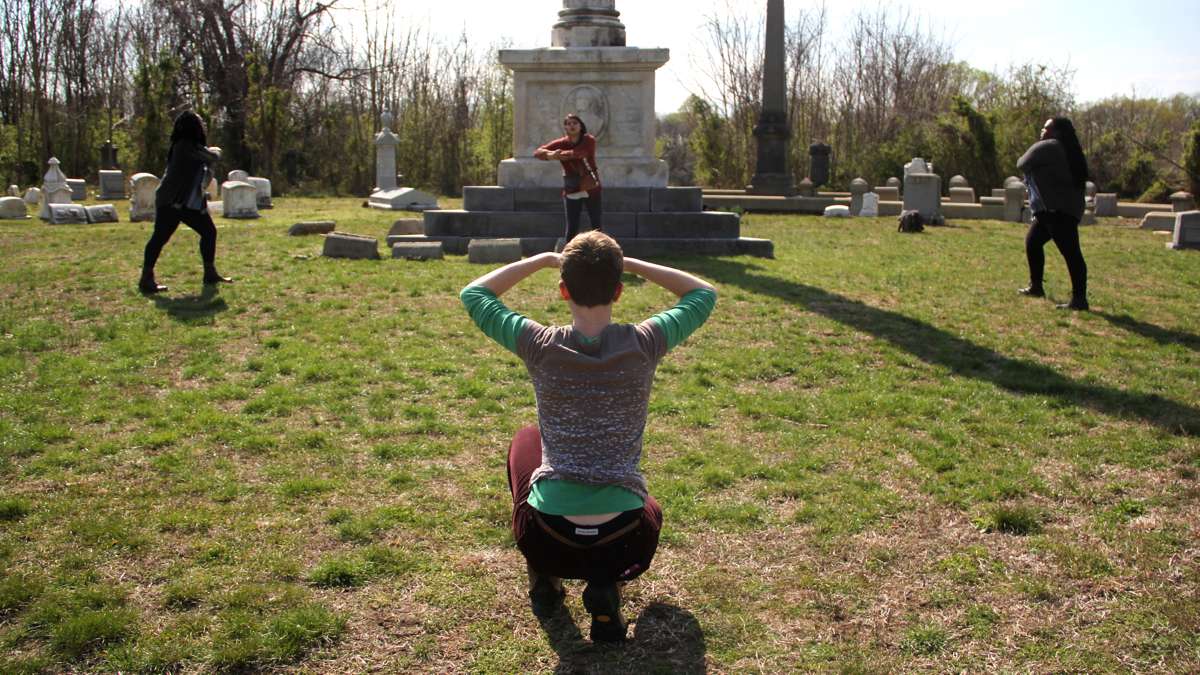

Maura Krause directs a rehearsal of Beowulf/Grendel from the base of a towering monument at Mount Moriah Cemetery in West Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

For most people, “Beowulf” was something they were forced to read in high school.

“I have to say it’s not my favorite story. It’s not a high school moment I connected to,” said theater director Maura Krause about the ancient, epic poem of the fight between the hero Beowulf and the monster Grendel.

“But I do love cemeteries. I love historic cemeteries, these wild places. The juxtaposition of the stone and overgrowth just really gets me,” she said.

Krause was asked by the Renegade Theater Company to direct Beowulf in the Mount Moriah Cemetery, a 200-acre burial ground in Southwest Philadelphia. Established in 1855, in recent decades it has been neglected, even temporarily abandoned. Headstones are toppled or missing, many have disappeared in overgrowth. In some places, the woods have completely taken over.

The play is a walking play; audiences follow the actors as they meander for about a mile through the cemetery. The two central characters, Beowulf and Grendel, split up several times, moving out of sight and earshot of each other. The audience splits, too, following one or the other.

This is the second production in Renegade’s “Great Outdoors” cycle. The first was “Planet of the Apes” staged in FDR Park during last year’s Fringe Festival.

“We wanted to be in a place that created an eeriness, with a forgotten beauty,” said Renegade artistic director Michael Durkin. “As well as see if we could drum up attention from the community. This is a really lovely, gorgeous place. We should help resurrect it.”

Renegade takes great liberties with “Beowulf,” the oldest existing long poem in the English language. Krause worked with the actors for months to devise a wholly original interpretation; the gap between hero and monster is narrowed; the confrontation is abstract; and the action becomes lyrical. For much of the play the two central characters are not named, so it’s ambiguous which is Beowulf and which is Grendel.

A narrator confronts the other two to get on with it, already.

“Tell me somebody’s going to get their arm ripped off pretty soon,” said Merri Rashoian as the frustrated narrator. “That’s what the story is all about. Either your sinews unravel until your shoulder bone cracks and you lose an arm, or you get an arm and you put it up on the rafters and it victoriously drips on all your false friends as you face your own mortality.”

Spoiler alert: Nobody’s arm is ripped off. Not literally, anyway. That’s the way the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery prefers it.

A few years ago the Friends started maintaining the land in the absence of any legal owner. In 2004 the last member of the Mount Moriah Cemetery Association — the organization responsible for the cemetery and the perpetual maintenance of its graves — died. There was no one left to govern the property, nor were there any funds to pay for upkeep.

The unusual situation set the cemetery adrift in strange legal territory, wherein there was a registered entity responsible for the cemetery and its interred remains, but no living persons who ran that entity. For 10 years the cemetery succumbed to nature and vandalism.

In 2014, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania named a newly formed group to be custodian: the Mount Moriah Cemetery Preservation Corporation. Maintenance of the 200 acres is taken on by the Friends group.

As part of the agreement with the state, the corporation will neither accept nor remove any remains. Paper records attest to who is buried there, including Betsy Ross, former city mayor William Smith, and singer-songwriter John Whitehead who co-wrote the R&B classic “Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now.” Unfortunately, it’s often unclear where exactly any particular set of remains rest.

The president of the Friends board, Paulette Rhone, wants to program the acreage with events to make it a destination for the living. That’s why she agreed to let Renegade stage its play there. But she has a few caveats.

“There will be no walking over graves. No blood and gore. Nothing that is at all disrespectful to those who are buried there, or the families who come to visit,” said Rhone.

This is the first play performed at Mount Moriah Cemetery; Rhone is watching the production carefully to make sure “Beowulf” is not too “Beowulf.” And that’s OK with the director. Krause wants the play to be less about tearing off an arm, and more about the legacies of heroes and monsters.

“It’s impossible to really change the story,” said Krause. “In the end, we have to stick with questions of a fight, of bodies, of ancestry, of telling stories about ourselves.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.