Two schools: 15 miles and worlds apart

-

Upper Dublin High School in Montgomery County. (Emily Cohen for WHYY)

-

Upper Dublin High School was redesigned to give students the best chance at achieving in higher education, with classrooms that resemble college lecture halls. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The campus at Upper Dublin High School has three seperate courtyards. This one is tended by students and has outdoor seating for an outdoor learning option. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The lighting fixtures at Upper Dublin High School were designed to make sure the light is diffused and less abrasive to the human eye than direct light. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Every two classrooms at Upper Dublin High School share a common room used at the descretion of the teachers for test taking, silent reading, group projects, and more. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The library at Upper Dublin High School was reimagined as a media center during the rebuild of the campus. The room is broken up into three parts, books, computers space, and tables for studying. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The library at Upper Dublin High School was reimagined as a media center during the rebuild of the campus. The room is broken up into three parts, books, computers space, and tables for studying. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Upper Dublin High School has a TV production room for its students to record news broadcasts and learn how to work with digital media. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Upper Dublin High School has a TV production room for its students to record news broadcasts and learn how to work with digital media. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Upper Dublin High School has a choir room, a band room, an orchestral room, and mulitple private practice rooms for students. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The performing arts auditorium at Upper Dublin High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The cafeteria at Upper Dublin High School has many options like pizza or salad for students to choose from. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The cafateria at Upper Dublin High School is open and spacious and allows students to eat outside in the enclosed courtyard. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The main gymnasium at Upper Dublin High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The aquatic facility at Upper Dublin High School is nationally ranked for its quality. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The aquatic facility at Upper Dublin High School is nationally ranked for its quality. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

A live weather station sits in the background as students take a science test at Upper Dublin High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

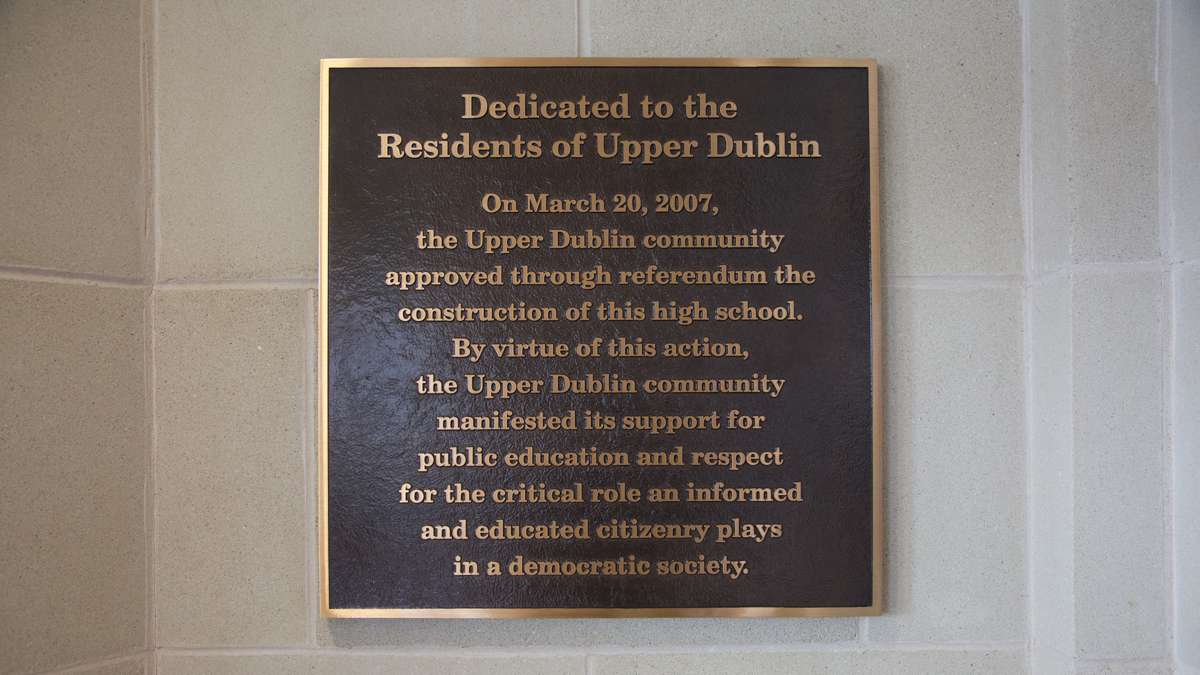

With the help of the Upper Dublin community, a total rebuild of the district high school was made possible in 2007. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Overbrook High School in West Philadelphia was one of 11 low-performing schools targeted for intervention. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The junior ROTC program is popular at Overbrook High School in Philadelphia. Students use what would be study hall periods to monitor the halls and assist teachers. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The auditorium at Overbrook High School in Philadelphia. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

An out-of-use science room sits dusty and broken due to lack of science teachers at Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The lone computer lab at Overbrook High School hasn't been updated in at least 5 years according to the principal. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Artwork with inspirational quotes and insignias of colleges adorn the walls of Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

A room under construction will be the home of a Career and Technical Education program at Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

Students pass though a stairwell at Overbrook High School. The school has 5 floors, only 3 of which are in active use, not incuding the basement levels. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

A broken piano sits in the auditorium since the music program was cut from Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The cafateria at Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

rtwork with inspirational quotes and insignias of colleges adorn the walls of Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

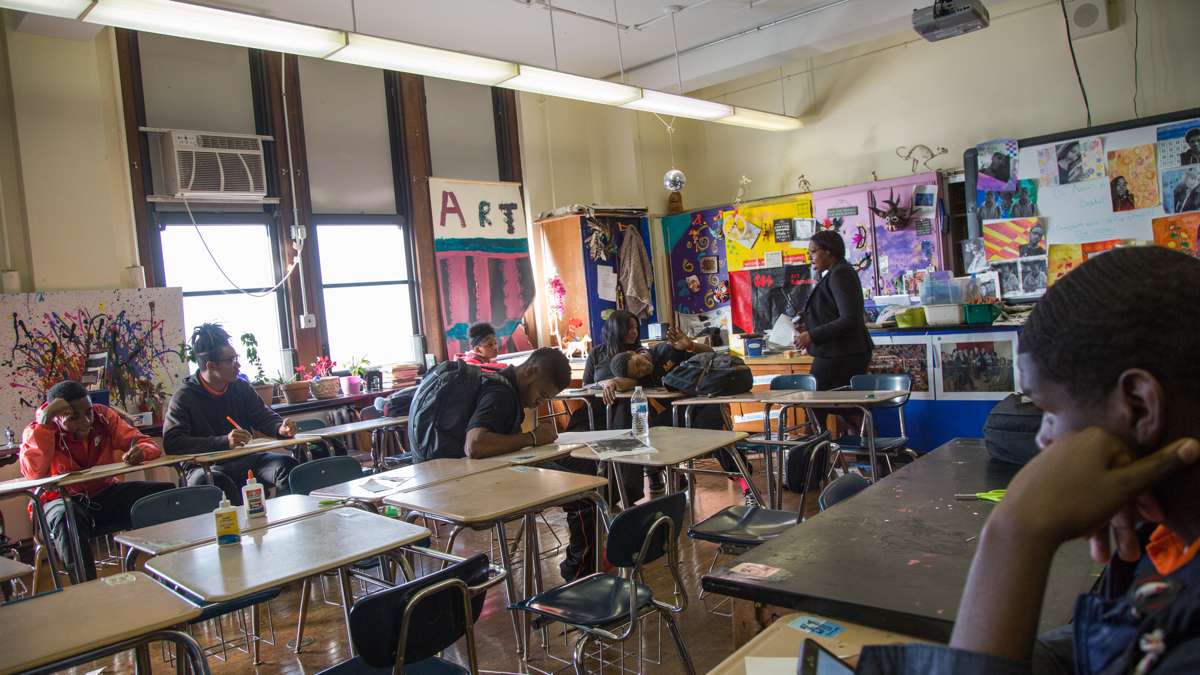

Students at an art class in Overbrook High School in Philadelphia in 2016. State Senator Vincent Hughes has cited Overbrook as an example of a school in need of repair. (Emily Cohen for WHYY)

-

Overbrook High School no longer has a music program and now has only one arts classroom for its nearly 600 students. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The passageway to the gym is covered in paintings done by the students at Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

The main gymnasium at Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

-

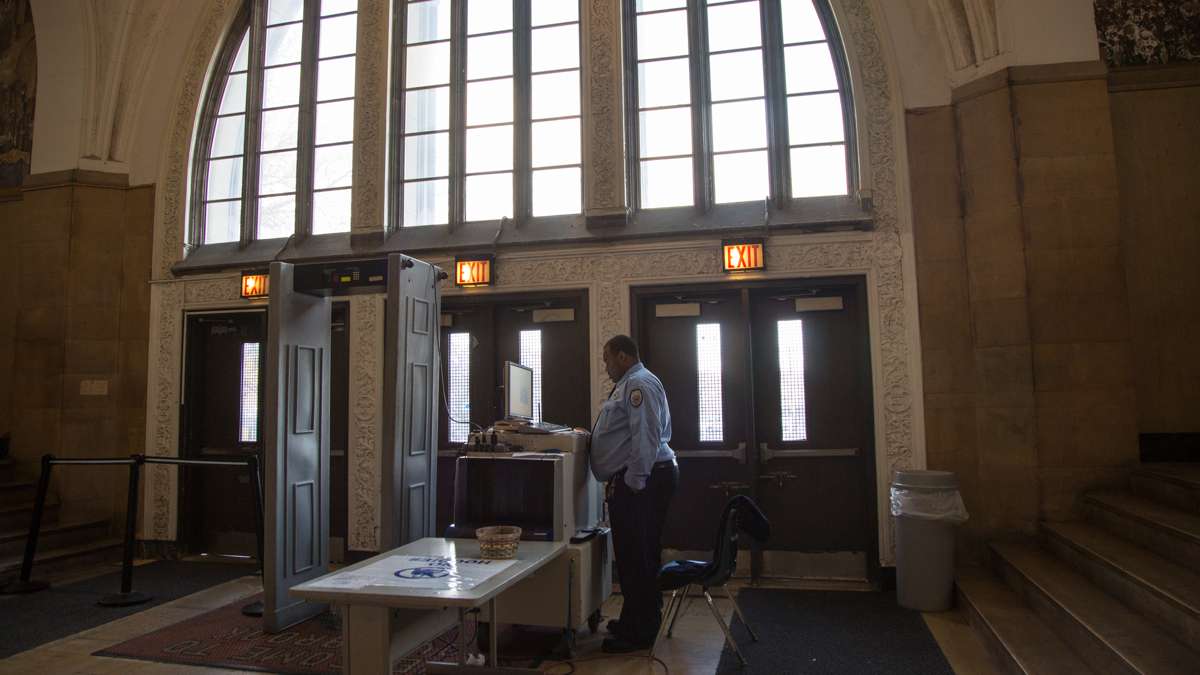

A metal detector and an x-ray machine sit at the enterance of Overbrook High School. (Emily Cohen for NewsWorks)

Upper Dublin High School in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, and Overbrook High School in Philadelphia are a mere 15 miles from each other. But they’re worlds apart.

Take the matter of water — that most basic element of human life.

Upper Dublin’s new high school, finished in 2012, features an 18-lane swimming pool with two spring-diving boards and a movable bulkhead that allows the pool to be configured for swim meets and water polo matches. The natatorium even has its own air-filtration system so the smell of chlorine doesn’t seep into the surrounding hallways or waft in the way of enjoying the tasteful mosaic that adorns the entryway to the facility.

At Overbrook — built in the 1920s — there is no pool. The comprehensive high school in West Philadelphia does have water, but it isn’t always in the right place or in the right state. Testing recently revealed six outlets with lead levels above the school district’s minimum threshold for lead content. Principal Yvette Jackson hopes to convert an abandoned room into a badly needed science lab, but can’t yet because the room has a drainage problem. The space fell into disrepair because budget cuts restricted the number of science teachers at Overbrook — and thus the number of science labs it could faithfully use.

Democratic state Sen. Vincent Hughes, who represents the communities surrounding Upper Dublin and Overbrook, toured both schools Monday to hammer home what he sees as the state’s funding inequities.

“It breaks my heart,” he said.

Reviewing the PlanCon funding formula

Hughes co-chairs an advisory committee tasked with re-examining a system called PlanCon — Pennsylvania’s byzantine process for seeking and receiving state dollars to aid local school construction projects. Through PlanCon, the state reimburses school districts that have undertaken the “construction of new schools, additions to existing schools, and/or renovations or alterations to existing schools to meet current educational and construction standards,” according to the state department of education.

PlanCon determines the amount districts receive through a formula that favors poor districts. Unfortunately for Philadelphia — where the average school building is about 70 years old — PlanCon money doesn’t go toward basic system maintenance unless it has an explicit educational purpose.

“In a lot of the projects that we do, when we go in, in many cases we’re not touching the educational spaces,” said Danielle Floyd, the district’s director of capital programs, in testimony before the PlanCon committee.

Philadelphia has about $5 billion in deferred maintenance, according to a just-completed district analysis of its building stock. As the district tries to chip away at that backlog, it may find much of the PlanCon money out of reach. And, with a capital projects budget of $172 million in the current fiscal year, there’s little hope the district can fix its problems on its own.

Philadelphia and other cities could at least get a boost if the state created new wells of state cash set aside for emergency maintenance or systems upgrades. Another fix might involve creating a rating system so that the state funds the most urgent projects first. Right now, money is doled out on a first-come, first-serve basis.

But any PlanCon changes will have to pass muster with Harrisburg Republicans, who likely won’t be as keen on spending millions to rehab sagging inner-city schools.

State Rep. William Adolph Jr., R-Delaware, pointed out that Overbrook is well under capacity at around 600 students. The school, which at one point accommodated more than 3,000 students, doesn’t use its fourth or fifth floors. Many of the city’s comprehensive high schools are similarly underused.

“Does anybody give any thought to — when you’re gonna build a new high school — just to build a bigger one,” said Adolph. “Instead of trying to maintain three high schools within five miles each other why wouldn’t we just build a bigger state-of-the-art high school?”

City schools at construction disadvantage

When it comes to school construction and repair, the role of state governments varied greatly. A dozen states have provided zero capital funding over the last 20 years, according to a report compiled by the Education Commission of the States and presented to the PlanCon advisory committee earlier this year. Another seven states provided funding at some point in the last two decades, but no longer do.

Some fiscal conservatives would almost certainly look at palatial new school facilities such as Upper Dublin High School and wonder if Pennsylvania should eliminate PlanCon and join the ranks of those who leave school construction to local districts.

Other states, however, make major investments in school facilities. Hawaii, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Wyoming, Connecticut, and Delaware all provide more than half of the total dollars dedicated to construction in their respective states.

Pennsylvania, at the moment, falls somewhere in the middle. Traditionally, the state earmarked about $300 million annually for PlanCon. That recurring funding was recently axed from the state budget and replaced with an $850 million bond that will cover outstanding payments.

From 1994 to 2013, Pennsylvania spent $7.3 billion on school construction. That was about 15 percent of the total money spent during that time, not far from the national average of 18 percent. In the Mid-Atlantic region, however, states tend to spend a lot more than Pennsylvania does. Delaware (57 percent), New York (36 percent), New Jersey (32 percent), Ohio (27 percent), and Maryland (26 percent) all doled out more proportionally in state aid for school capital projects.

Even if Pennsylvania decided to invest more in school construction and direct more of that money toward poor, urban districts, it would only make a dent in the overall gap between the haves and the have-nots. That’s because big-picture school districts disproportionately carry the tab when it comes to capital projects.

Nationwide, local dollars account for 82 percent of all school facilities spending, according to a 2016 report from the 21st Century School Fund. Another 18 percent comes from states, while the federal government provides nothing.

Compare that to operating costs, where the average school district receives 45 percent of its money from local taxpayers, 45 percent from the state, and 10 percent from the federal government.

Money from the state and federal governments is typically used to plug the budget holes of poorer districts and help even the playing field. When it comes to capital costs, there is a lot less smoothing — and therefore a greater chance of disparities developing between districts.

Upper Dublin: A case in point

In 2007, the district’s taxpayers agreed to borrow $119 million to help build the high school that now has become one of the most stunning in the region. In addition to its natatorium, Upper Dublin has three interior courtyards; a tricked-out television production studio; separate practice spaces for the choir, orchestra, and band; something called a “guitar lab”; a black box theater; and a gorgeous main stage theater that principal Robert Schultz likens to the Kimmel Center in Center City Philadelphia.

English classrooms feature two spaces — one set up for a typical class discussion and another dedicated to small-group learning. The wall separating the two areas has a large glass partition on which students can doodle.

In one such classroom, a teacher proudly displayed autobiographical poems written by her 10th-graders — one of them an immigrant from Cambodia.

The final stanza of this particular poem summed up, rather neatly, the yawning gap between what greets the students of Upper Dublin and Overbrook every morning.

I am from philly

Where I always thought fighting would solve problems

Started from the bottom

Now I’m here.

Correction: A prior version of this article mistated the size of the bond the state of Pennsylvania secured to pay for school construction. It is $850 million, not $850 billion as originally stated.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.