Trade School brings Detroit artists to mingle with their Philadelphia counterparts

The Trade School art festival in a variety of venues across Philadelphia brings Philly and Detroit artists together for collaboration.

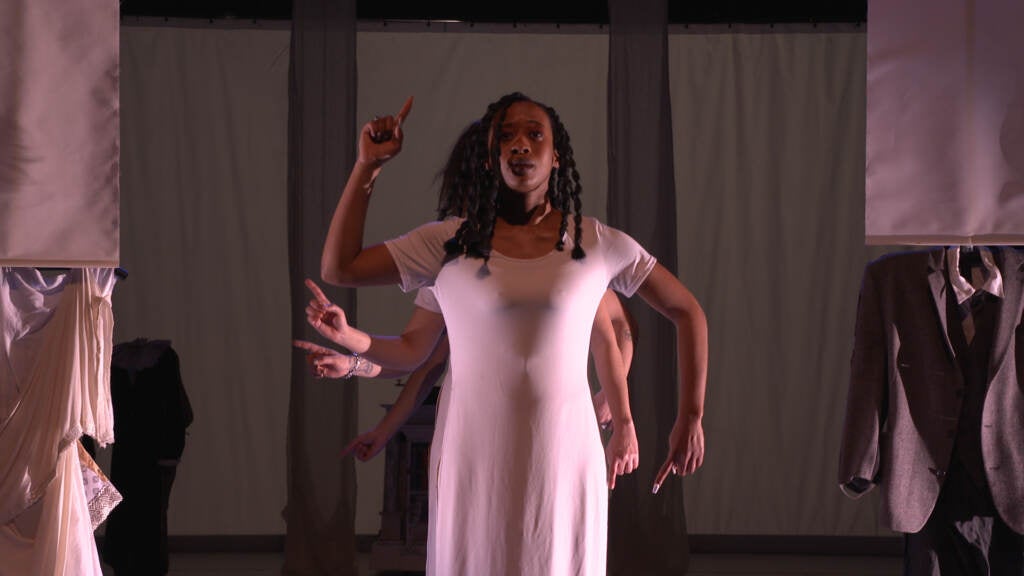

Thomas Choinacky and Severin Blake, performers with Applied Mechanics, perform the piece “The Colonialists” earlier this year at Ball State University, in Indiana. (Courtesy of Applied Mechanics)

Back in the “pandemic winter” of 2021, when many arts venues were forced to shut down again due to a surge in COVID-19 infections, Emily Bate said she finally overcame her aversion to online performance art, something the Philadelphia-based composer had been avoiding until then.

“I was a person who did not see a lot of Zoom plays or anything like that,” she said.

This time it was different. Bate was tuning into the second iteration of Trade School, a festival of performance art connecting local Philly artists with their counterparts in other cities. The festival started in 2019 with artists from Los Angeles, and was supposed to happen again in 2020 with artists from Detroit.

Due to the pandemic, the first phase of the Detroit version of Trade School became an online festival. As a participating artist, Bate felt invested: she grew up in Holly, Michigan, about 50 miles from Detroit.

“I was surprised by my level of buy-in for Zoom activities at that moment,” she said. “I knew one day we would be together. I was really hungry for artistic connection.”

Now, that day of connection has finally come: This week Trade School has opened as an in-person festival in a variety of venues across Philadelphia, bringing Philly and Motor City artists together in the same room.

It’s what founder Sarah Bishop-Stone originally intended.

“Artists are all super resourceful and really smart, and have come up with different strategies to make their work and to make their life,” said Bishop-Stone, creator of the festival’s parent organization, The Philadelphia Thing. “Especially in cities that are not the major cultural hubs in the U.S. We’re trying to start a conversation between artists in different cities about those strategies, about how to create work along with creating a sustainable life.”

One of the Detroit artists is Sherrine Azab, co-founder of the performance company A Host of People and a producing partner of Trade School. As a “multi-racial, queer-centered, devising theater ensemble,” she said AHOP is not in the mainstream.

“We live outside of a perceived cultural capital. We don’t live in New York or L.A. We live in Detroit,” said Azab. “Our work definitely has Detroit fingerprints all over it.”

A Host of People will perform “Cleopatra Boy,” an original work inspired by a line from Shakespeare’s “Antony and Cleopatra.” Moments before poisoning herself, Cleopatra despairs over her posthumous legacy when she imagines herself being portrayed by “some squeaking Cleopatra boy, my greatness in the posture of a whore.”

“We are looking at how her story got retold primarily by white men many years after she died,” said Azab. “That is a pattern we see happening historically to women, people of color, and queer folks. Their narrative can be taken by others and be construed in a certain way. We are using that to show how we want to take our narratives back.”

Azab said none of the Detroit artists have ever performed in Philadelphia before, perhaps with the exception of Ahya Simone, a sought-after experimental harpist and filmmaker.

Much of the work presented in Trade School is meant to be challenging.

Bate’s piece, “Wig Wag,” is based on a choral composition written for a vocal quartet, but the performance extends to the audience who are expected to sing along, whether they want to or not.

“The show is trying to make space for a variety of comfort levels,” said Bate. “A big part of my work as an artist is about taking people who wish secretly that they could sing and giving them permission to do it.”

Even if you have never secretly wished to sing in public, there is also space in this piece for you. Bate does not expect everyone to be enthusiastic, designing “Wig Wag” to reflect a broader society.

“The white Western choral music tradition I came up in — there’s a lot of beautiful things about that tradition, but a thing that is strange to me is the idea that everyone is trying to sound the same,” she said. “I’m interested in making music where we just acknowledge that we’re all constantly impacting each other, and the impacts are all over the map. We don’t have to aspire to a conformity of reaction.”

“Wig Wag” is still in development, and is not the final version of what Bate hopes the piece will become. Part of the vision of Trade School is training the audience to embrace the artistic process, not just the product.

Bishop-Stone believes that including audiences in creative development is essential to a post-pandemic art world.

“In 2020 and 2021, I really stopped having any expectations about what ‘finished’ means, in terms of when a work meets its audience,” she said. “Part of the way we should be considering moving forward is: How can we be malleable, both as artists and audiences, to the special relationship of showing work now.”

One of the performances will be “The Colonialists” by the Philadelphia ensemble Applied Mechanics. The immersive theater performance will divide the audience into groups to be led on different walking paths through the University of the Arts’ Gershman Hall.

The different audience groups will be goaded against each other, becoming actively complicit in colonialist mentalities of inherent superiority.

“Fake standards of beauty, fake standards of excellence, fake clubs of who’s in and who’s not, standards of who is an expert and who is not, so that even the most ridiculous statement, when it’s made by someone who has a certain credential, is able to pass as absolute truth,” explained troupe member Mary Tuomanen. “All of these are complete falsities, emperor’s new clothes, creating factions, dividing a populace up.”

“The Colonialists” has been performed once before, at the invitation of Ball University in Indiana, where Applied Mechanics customized the performance to take aim at the higher education industry. At UArts (or “UFarts” as the actors cheekily say) the target is the arts industry and the protection of its own curatorial expertise.

“The one thing I can promise about the show is that you will start to see the language of colonialism a lot more often, and see it as the flimsy tool it is,” said Tuomanen. “Though its effect is brutal, it is a silly, flimsy tool. It’s inherently absurd.”

Tuomanen sees a kinship between Applied Mechanics’ way of implicating the audience in its social critiques, and the performance tactics of her counterparts from Detroit. She calls it “shoestring maximalism,” packing a critical punch while operating with few resources in the margins of mainstream theater.

“Detroit has its own flavor, but it does feel like a generational zeitgeist, a generational movement where art is not detached from our activism, it’s part of it,” she said. “We’re pointing out silly systems we don’t want to be part of, and growing into an imaginary world. We have to imagine the world we want.”

Although Trade School is designed to bring artists from different cities together, they will not be directly collaborating with one another during the festival. Bishop-Stone has (finally!) brought people into the same room to share ideas and experiences. What comes next is anybody’s guess.

“We may not see it this week. We may see it in the future,” said Bishop-Stone. “A lot of the conversation between the works will happen in the audience and, you know, at the bar after the show.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.