Thousands of miles from home, Afghan evacuees start new lives, schools in Philadelphia

The local Afghan community, centered in Northeast Philadelphia, has nearly doubled with the influx of evacuees, who worry for family and friends left behind.

Listen 7:37

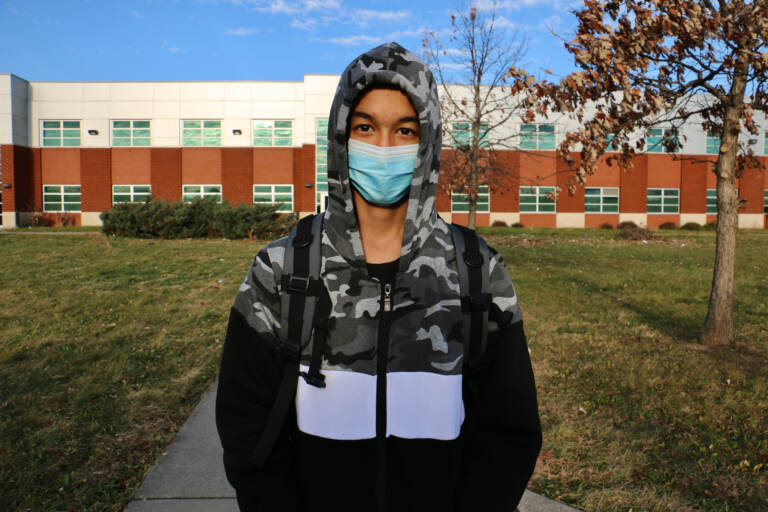

Ali Wahaj Mosakhil, 15, arrives at Samuel Fels High School for his first day of school since emigrating from Afghanistan. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

After an evacuation flight out of Afghanistan, two months at Fort Dix military base in New Jersey, and a month in a Center City Airbnb waiting for more permanent housing, Ali Wahaj Mosakhil was finally headed to his first day of high school in the U.S.

But before the 15-year-old could walk through the doors of Samuel Fels High in Northeast Philadelphia, he had to learn how to get there.

On an early morning in December, he and his dad stood at a bus stop near their family’s new home in Olney. Michelle Ferguson, with the refugee resettlement agency HIAS Pennsylvania, repeated the name of the SEPTA bus he needed to catch.

“26 to school. 26 home,” she said. “Same thing.”

Ferguson helps newcomers like Ali Wahaj get enrolled in high school, and escorts them to the first day of class.

But by the afternoon, the teen would be on his own to navigate the 30-minute bus trip back home through his new city. He doesn’t have a cell phone, and tried to commit the steps to memory.

All morning, his dad, Esmatullah, had been worrying over his son’s safety. What would happen if he got lost?

As they rode the bus, Ali Wahaj sounded nervous too.

“I don’t know where is my home,” he told Ferguson, after she explained, once more, he would need to take the bus home.

“You don’t know the address? Okay, we can write it down at school. I will not, we will not, lose you,” she said.

It’s a lot of information to take in at once, and dozens of Afghan families in Philadelphia have lived some version of this scene since the U.S. withdrawal last summer.

The local Afghan community, centered in Northeast Philadelphia, has nearly doubled with the influx of evacuees, adding 650 new people. Resettlement agencies predict around 200 newly arrived Afghan students will be enrolled in local schools once all the families are processed.

At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic has strained the American education system, and the handful of agencies designated to help arriving families are scrambling to meet the need.

‘An unprecedented situation’

The U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan has raised questions about what America owes to its allies there after two decades of occupation. Tens of thousands of people who supported the U.S. efforts in Afghanistan were left behind, according to estimates by State Department officials.

The stakes are stark for those still there now living under the Taliban government, especially for women, the free press, and those who aided the U.S. military. Many of those who made it, including the Mosakhils, had to flee suddenly.

Esmatullah worked supplying auto parts to the U.S. Army for more than a decade, living in a northern province of Afghanistan. When the Taliban took over the area in mid-August, he and his family traveled hundreds of miles across the country to Kabul.

Then, as Kabul fell, they raced to the airport. They brought little with them, beyond the clothes on their backs and some documents proving Esmatullah had helped the U.S.

“I had a good life in Afghanistan,” Esmatullah said through an interpreter. He never imagined everything would fall apart so quickly.

Those who made it to the U.S. are encountering a support system that dwindled due to Trump administration cuts to refugee resettlement efforts, an issue compounded by a dearth of affordable housing in Philadelphia.

Even in the best of times, the runway to self-sufficiency for refugees in the United States is short. The federal government pays refugee resettlement agencies to help Afghan evacuees set up their lives for about 90 days. After that, some piecemeal programs exist to help with the transition, such as afternoon ESL classes, but full service support ends.

“It’s really tough,” said Valeri Harteg, the refugee education program manager at HIAS Pennsylvania, noting that some other countries provide a longer runway to self-reliance.

“Some families will have relatives and friends be resettled in other countries that have longer periods of resettlement … and the U.S. is not like that. It’s really fast. Really short.”

The evacuation of Afghanistan put a lot of people into this pipeline, all at once. After the airlift, the Biden Administration requested funding to resettle 95,000 Afghans in the United States by September 2022. Local refugee resettlement agencies said they have already welcomed the bulk of those they expect to help, around 650 people since late September. Around one-third are school age children.

Under normal circumstances, getting kids up to speed who may have missed grades, or never been in formal school, is hard. On top of that, the coronavirus pandemic has caused widespread disruptions and staff shortages in Philadelphia public schools. In the fall, hundreds of teacher and staff vacancies caused staffing shortages so great that administrative staff were sent to fill the gaps. This January, more than 100 schools paused in-person learning due to the omicron variant.

All of this is happening as Philadelphia schools attempt to absorb new Afghan students that require extra support to thrive. “It’s an unprecedented situation, I think, for the school district in many ways,” Harteg said.

Combine that with the COVID-19 pandemic and virtual schooling, and it’s even more complicated.

“Especially for families that are pre-literate and have very little to no digital literacy, explaining to click here and type in a password [to access your virtual class] means quite literally nothing to them,” said Parisa Khoshnood, a member of HIAS Pennsylvania’s education team.

She remembers one student who needed a whole lesson on what clicking meant.

“We toss that word around so casually because to us, it’s such a norm,” she said. “But he had a blank face.”

Her team leads newcomer parent workshops that serve as a sort of crash course on the U.S. education system, explaining everything from the differences between district, charter, and private schools to school attendance expectations.

They also spell out the rights newcomer students and their families are legally entitled to, like in-person or telephonic interpretation.

“Students who are still learning English have the same rights and deserve the same quality of education as other students who are native English speakers,” Khoshnood stressed during a virtual workshop in December.

Lifeline to freedom

Philadelphia public schools enroll many immigrant students, and more than 16,000 students learning English as a second language, hailing from countries from all over the world.

But, historically, there haven’t been many from Afghanistan.

There were 126 Afghan-identifying students enrolled in the district as of Jan. 24, according to data shared by the School District of Philadelphia. So far this school year, refugee resettlement agencies have helped enroll 47 Afghan students, said Harteg. Dozens more are in process, and about 100 behind them.

The district has more than 100 Bilingual Counseling Assistants (BCAs) to help newcomer families, but only one of them in the entire city speaks Afghan languages. A new job posting for an assistant who speaks Dari has gone unfilled since April, and the paperwork for registering for schools isn’t available in the languages spoken in Afghanistan.

In early December, Ali Wahaj and his dad spent three hours on Zoom, going through the process question-by-question with Michelle Ferguson from HIAS PA and an interpreter on speakerphone.

At the time, the family was staying in an Airbnb, a sleek Center City apartment with white brick walls and a sweeping view of the Ben Franklin Bridge.

Esmatullah marveled at the structure, and his family went for long walks across the bridge. After living in fear as the Taliban took over, it felt freeing to be out in the open together.

“There’s no tension,” Esmatullah said through an interpreter.

Philly’s affordable housing crisis has meant new families like his often end up scattered across the city, in temporary housing, before finding more permanent places.

That pushes back the timeline for starting school, since children generally can’t enroll until they have a permanent address.

“A lot of our current students have been delayed a little bit in the school enrollment process, because there is such a large housing shortage at the moment,” Khoshnood said.

HIAS PA had finally found the Moskahil family a home in Northeast Philly, one of the main neighborhoods where they try to resettle evacuees, since there is already an established Afghan community there.

With their address locked down, the family could start the school enrollment process.

Part of that process involved troubleshooting questions that don’t necessarily make sense for newcomers. Who do you list as an emergency contact, when you’re new to the country and don’t know anyone here?

It also involved re-creating Ali Wahaj’s transcript from memory. Many Afghan children fled the country without school records, so the district is letting them self-report their grades, to the best of their memory.

He recounted his scores, out of 20 points, beaming when he got to his favorite subject.

“I love biology,” he said. “20 out of 20.”

Grateful, but cautious

About a month later, Ali Wahaj had just finished up a day in his fifth week at Fels.

His two younger siblings, dressed in their charter school uniforms, played with the neighbor’s pregnant cat, talking excitedly about how they’d been promised one of her kittens.

The transition to school for the trio has been bumpy. The siblings only had a few weeks of classes under their belts before school temporarily went remote, as COVID cases surged.

“At the beginning, we had a really tough time joining the classes,” Esmatullah said through an interpreter. The younger kids were disappointed they didn’t have the chance to change into sweatpants for gym class.

But eventually, they got the hang of it.

Meanwhile, Ali Wahaj is still adjusting to his commute to school.

On his first day at Fels, he took the wrong bus home and got lost for five hours, without a way to get in touch with his family.

He eventually found a cell phone store that let him call someone from the refugee resettlement agency for help.

But Ali Wahaj seems to be taking it in stride.

“It was an experience for me so I have to be very cautious,” he said through an interpreter.

His dad, Esmatullah, says as stressful as that was, he wants to make something clear.

The family is safe. They have a home.

Esmatullah can’t say the same for relatives in Afghanistan. His sister and brother also used to work with U.S. forces, but didn’t get out in time, he said. The Taliban sometimes comes looking for them.

“They are not in one place. They are in hiding,” Esmatullah said. “One week, one place, [another] week, another place.”

They are who he worries about now. By comparison, life in the United States is not as stressful.

And Ali Wahajs is no longer the newest Afghan student in his classes. One girl had started the day before.

Esmatullah said he told his son to help the new student.

Ali Wahaj laughed in response.

“I myself need help!” he said. “Fels is so big!”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.