This star Philadelphia principal urges graduates to ‘rebuild the world’ in their vision

Last year, Richard Gordon, who is now the principal of Paul Robeson High School for Human Services in West Philadelphia, was named the National Principal of the Year.

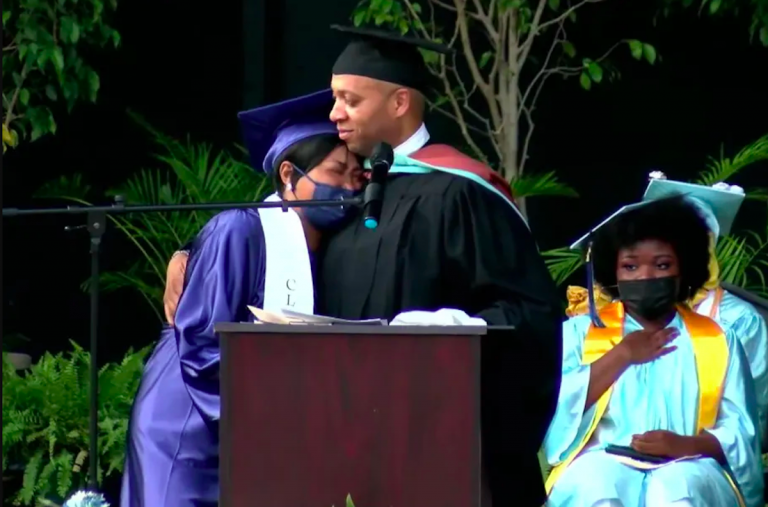

Richard Gordon, principal of Paul Robeson High School, consoles Tawanda Robinson, mother of David Williams, who was gunned down in 2020. Williams was set to graduate this year. (Johann Calhoun / Chalkbeat)

This story originally appeared on Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

As an African American male — a demographic underrepresented among educators — Richard Gordon learned quickly how much of an impact he could have on students and their families when he became a teacher in Baltimore.

“There is nothing more rewarding than seeing the evidence that the educational environment and experience you provide your students, or the love and care you showed them, made an impact on how they see themselves or how they see the importance of school,” Gordon told Chalkbeat.

Last year Gordon, who is now the principal of Paul Robeson High School for Human Services in West Philadelphia, was named the National Principal of the Year. He was recognized for helping Robeson get off the state’s list of low-performing schools and onto the list of “high progress schools,” with a graduation rate of 95%.

But it was COVID that presented the greatest hurdle of his career. In addition to leading a school through more than a year of remote learning and difficult personal circumstances stemming from the pandemic, he also helped them navigate traumatic grief. One of his students, David Williams, was gunned down in Southwest Philadelphia in May of last year and was set to graduate this year.

At Thursday’s commencement, Gordon awarded Williams’ mother, Tawanda Robinson, with a spirit award named in her son’s honor.

“No loss that we’ve had was more devastating than losing our own beloved David Williams,” Gordon said before some 70 graduates who had gathered at the Dell Music Center. “Even though his body was stolen from us, his spirit will never go away.”

Despite the challenges the school community faced during remote learning, Gordon called this year’s class “amazing.”

“They completed high school, and they did it during a global pandemic,” he said. “And they did it during the social unrest that has been going on in this country. And they are going to be the next group of leaders to make sure to fix the things that our generation didn’t get a chance to address.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

I was born and raised in Camden, New Jersey, often labeled in the ’70s and ’80s as either the “poorest city” or the “most dangerous city” in America. My father was a known drug dealer who was incarcerated and absent from my life at the age of 12. He left me and my youngest brother in a home with no food and no utilities for three days when he was unable to make bail. My mother then raised us on a hairdresser’s meager salary in Philadelphia. For more than five years, she would wake up every morning at 5 a.m. to drive me to school in New Jersey, subjecting herself to possible fraud charges by illegally using her best friend’s address to ensure that we received the best education she could possibly provide for us.

To succeed in an environment where my students are categorized as having a 100% poverty rate and are 100% minority — 95% are African-American — I’ve followed the best advice I got from my mentors in Baltimore: have genuine empathy (not sympathy), understanding, and unconditional love for all students I am privileged to serve. It is my knowledge and personal experiences that provide me with unique insight into how generational poverty, mental illness, family dysfunction, unprecedented waves of gun violence, and the inequity of the criminal justice system can predetermine our life’s outcome. I use my credibility and influence with my students to not only promote empowerment through academic success, but also through the understanding that education and personal empathy for your fellow human being empowers you with the opportunity to change your life. I am taking my personal history of pain and using it to both heal and to inspire my students to reach greatness they don’t always imagine for themselves.

What was your biggest misconception that you initially brought to being a principal?

The one thing I believed that is far from the truth is that principals had to know everything and have an answer/a response for every situation that came to his/her attention. It’s not a matter of whether or not I knew the answer or what to do. True sustained success comes as a result of the collaboration and collegiality amongst all staff members in the building, from teachers to our support staff. I learned their roles are critical to true transformation and innovation that is needed to motivate our students and families to give us their absolute best, despite oftentimes challenging personal circumstances.

Academic leaders say many of the lessons Black male teachers bring to the classroom go far beyond academic content and pedagogy. Do you agree?

Totally! I am proud to be an African American male educator. Our impact and obligations as educators go well beyond the walls of our classrooms and schools. I am most proud to share with our students the amazing contributions to our society African Americans must and do make every day. I share with my students every day how we are the dream of our ancestors, those that came before us who fought, led, and gave the ultimate sacrifice for us. We have an obligation to our Creator: our collective success must become the norm and not the exception. I love having the opportunity to show other Black males each day that Black men also have opportunities for success if we are willing to work hard and band together in support of one another.

How have your students been affected since the COVID closed schools last year?

We have seen a significant increase in the number of students working and/or needing/seeking employment in order to supplement their families’ income (or just to have money to absorb their own expenses, so they aren’t burdening their families). This year, more than 80% of our senior class is holding down jobs while in school. However, the greatest concern was in our 10th grade class, where we have seen a significant increase in the number of students who have become work-eligible at 16 and work several days a week after school. This has significantly impacted their grades.

We’ve had an increase of students experiencing serious food and housing insecurity, where the families have to be split up amongst relatives just to survive.

What’s your message to graduating seniors who had an all-virtual school year?

To all students in the City of Philadelphia, I implore you to recognize your unlimited potential. Although minorities in our city and in our country are still bound to the same indignities and discriminatory practices of America’s painful past, we are truly in a time where the possibilities for healing are endless. Minorities are in a great position today to lead the healing process, lead the reconciliation process, and lead the eradication of poverty and the wealth gap stigmatizing many of our neighborhoods. Whatever road you choose to travel, I want you to reject the idea that what you see in front of you is the best we can do. I want you to see the status quo as nothing more than a starting point to rebuild the world in your vision, use your passion to accelerate transformational change, and stop society’s most destructive instincts. It’s a big assignment, but I truly believe this is your time to get it done. Embrace the moment! For if not you, then who? If not now, then when?

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)