The messy necessity of community buy-in for Philly’s supervised injection site

Rutgers sociologist Stephen Danley complicated question of how to achieve community consensus on controversial projects, reframing issues of power.

People in support of and opposed to Philadelphia’s proposed supervised injection site protest in City Council. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

South Philadelphians said no, and the potentially historic supervised injection site at Broad and McKean Street went up in smoke. The effectiveness of that opposition brings up questions about the role that the community should have in city decision-making. It is an argument with familiar adversaries: On one side are those who argue that living in a place ought imply control over it. On the other: those who argue that community voice often comes from privilege and leads to exclusion. It is an argument that begs the question: Has community participation outlived its usefulness?

This is the other side of creating a cult of community. Too often, we consider community voice a kind of pixie-dust — sprinkle it on problems to solve them. It is anything but. Incorporating community voice into decision-making means platforming the bias that lives at the community level. It is messy and complicated. But it is also one of the only ways of reckoning with the reality of what happens once a supervised injection site (or affordable housing) opens in a neighborhood. A community may be biased, but a community buy-in can also be necessary for such institutions to not just get approved, but to succeed in their new neighborhoods.

“[This] is about power: who should rightfully have the power to make a community and who should have a say in decisions about urban development.” – Balzarini and Shlay, Gentrification and the Right to the City: Community Conflict and Casinos (2016)

The conflict over the supervised injection site in South Philadelphia has taken a familiar form. On one side are healthcare professionals, those closely involved in the addiction community, and progressives who argue harm reduction is good policy. On the other side are a host of community groups arguing we need to protect our neighborhood. That protection often takes the form of NIMBYism—which stands for Not-In-My-Back-Yard—and is often used by neighborhood groups to fight anything seen as undesirable coming to the neighborhood. From affordable housing, to nuclear waste disposal, to facilities for the homeless, NIMBYism has come to represent the triumph over neighborhood self-interest over communal needs. And NIMBYism’s power comes from its ability to channel the views of a community’s residents into political power. Take, for example, this viral clip of a South Philadelphian challenging former Governor Ed Rendell, which gets to the heart of a community claim to control.

Passionate exchange from a South Philly mom to Safehouse official and Governor Rendell. Says they sprung this on community @NBCPhiladelphia pic.twitter.com/iuixVnuMOP

— Miguel Martinez-Valle (@MiguelMValle) February 26, 2020

“You don’t sit there and live in that community. You don’t walk on date night like my husband and I do, to Passyunk Ave. You don’t take your kids to daycare like I do.”

This is a deep appeal to ownership of community, one that is grounded in the daily act of living somewhere. It has powerful rhetorical appeal. But if community participation is going to work, it needs to be challenged. The famous geographer Dr. David Harvey warns that a claim to represent community can be “an empty signifier. Everything depends on who gets to fill it with meaning.” Here, that meaning gets claimed by a particular type of Philadelphian, one who has “generations of families, who don’t leave, who have college degrees, who sit there and stay in their community, who raise our children there.”

And this is the crux of the debate over community participation: Who gets to be community?

Notice who is left out or considered unworthy of such participation. Those without college degrees. Those who recently moved to the neighborhood. Those without children. And, of course, those families desperate to find a better way to deal with addiction.

Protecting a neighborhood has always been a double-edged sword. The mantle was taken by those who opposed school busing, but also by those seeking to protect their neighborhood from urban renewal, such as in the District of Columbia, where Martin Luther King Jr. once told residents to “prepare to participate.”

Participation has often been glorified, but it’s never not been complicated.

In part, that is because community itself is considered unified, when it is often anything but. In practice, what we call community is almost always a coalition. To paraphrase Tolstoy: All support is alike; everyone opposing development opposes it in their own way.

Nowhere is that more true than what we are seeing in South Philly. A quick perusal of the Taking our South Philadelphia Streets Back Facebook Page, a linchpin of injection-site opposition, shows the diversity of reasons for doing so.

Some oppose supervised injection sites on moral grounds; they do not want to support what they see as a moral failure.

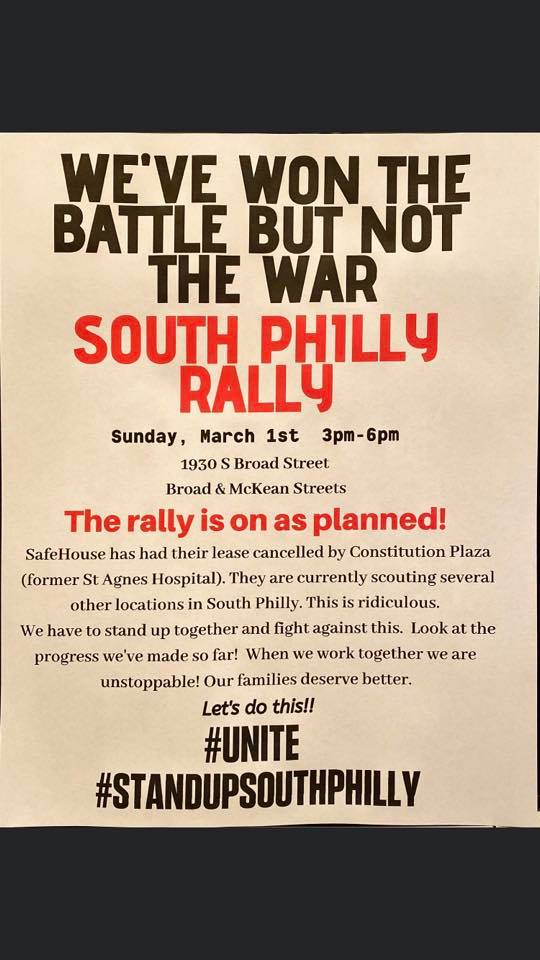

Others, such as the author of this flier, oppose the site at all locations, presumably to protect their community.

Still, others have more nuanced concerns about the appropriate location for a facility, and how close it ought to be to schools or playgrounds. To make matters more complex, those with more extreme views often hide behind the most nuanced ones.

So ought we just throw out the NIMBYs? And with them, participation?

It’s complicated. Part of the complication is that without community buy-in, there is a significant risk for long-term political blowback that reduces the likelihood of supervised injection sites receiving the support they need to succeed. The opposition to supervised injection sites has already received significant support within City Council — endangering future sites. Without buy-in, short-term gains in harm reduction may lead to a long-term backlash.

Even in the short-term, community buy-in is critical. Community support can help ensure that businesses around the site are supported rather than stigmatized, that patients are treated with dignity and respect, and that injection sites are seen as part of the solution to the community’s challenges with addiction rather than exacerbating them.

We need to contend with this issue in the longer term, but I stand by my assertion that the first safe injection site in America should not be imposed on a community by force of political will. We do harm reduction; everything we are about stands against compulsion. https://t.co/IHD7zL4Pwe

— jeff deeney (@jeff_deeney) March 4, 2020

This outcome, in which a significant portion of the community embraces and supports a supervised injection site, requires acknowledging that community opposition is not the only community, then building a different community coalition for support. That coalition would include mothers with concerns about their children, and ask them to contribute to choosing a location. It would define community as including families facing the challenges of addiction, then ask them to tell their stories when possible. It would ensure participation is accessible and, to the extent possible, welcoming.

Building that coalition will be difficult. It will require neighbors talking to neighbors. Education about the benefits (and risks) of harm reduction. And politicians working with, rather than around, their constituents.

In other words, it’s going to require a whole lot of community participation.

Dr. Stephen Danley is the graduate director of the MS/PhD in Public Affairs and Community Development at Rutgers University-Camden. He is a Marshall Scholar, Oxford and Penn graduate, and author of A Neighborhood Politics of Last Resort: Post-Katrina New Orleans and the Right to the City. You can find him on Twitter @SteveDanley.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.