Teens push for better services, culture surrounding mental health in Philly schools

Philadelphia student organizers want City Council to set limits on tests and require teacher training on trauma-informed care.

Listen 1:49

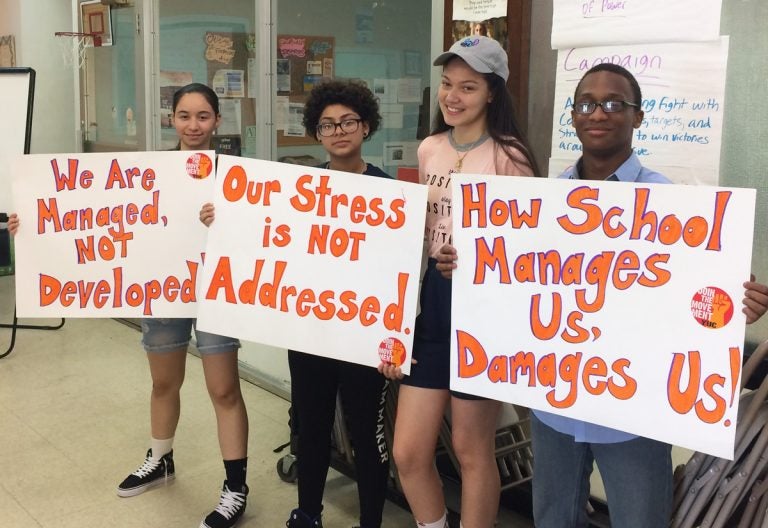

(Second from right) Yesenia Rodriguez, a 16-year-old junior at Central High School in Philadelphia, and her fellow organizers with Youth United for Change prepare to petition City Council for improvements to mental health services in schools at the School District budget hearing on Wednesday, May 16, 2018. (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

Yesenia Rodriguez is stressed out. The 16-year-old junior at Central High School in Philadelphia said it’s not uncommon for her to cry in the school bathroom over a test score.

“It just feels like I’m below average — like I’m not where I’m supposed to be,” said Rodriguez of getting a poor grade.

“It’s like my self-worth is equated to this number,” she said. “And if that number isn’t high enough, then I’m not worth anything, then I don’t actually have the potential to go anywhere in life.”

A few problems are contributing to high stress levels among her classmates, Rodriguez said. One is a school culture she believes expects students to work as hard as they need to in the name of passing tests and preparing for college, regardless of students’ well-being.

“I feel like a lot of people, they’re always like, ‘Oh, stress, it’s a part of life, this is gonna prepare you.’ But not if it’s chronic and toxic,” said Rodriguez, who said she and her classmates often stay up until 1 a.m. studying, have more than two tests a day, and skip meals to complete their work.

The other issue, she said, is that many of her classmates have tough home lives that make it harder to handle the academic pressures that someone with a stable home support network might be able to take on.

“A lot of students are going through poverty and race relations and just familial problems — and at the moment, they don’t really know where to turn to,” she said.

Rodriguez said she’s not able to confide in her parents about her stress levels. Because they didn’t go to college, she said, they don’t fully understand the rigorous college preparatory environment.

Central High School is a public magnet school with a selective admissions process. It performs in the top 5 percentile of Philadelphia schools on test scores. In fact, Central hovers around the top of the charts on most metrics: very high retention and graduation rates and no in-school suspensions. But when students were asked to rate the climate of their school, only 63 percent gave positive responses. Thirty percent responded positively when asked if they felt college and career ready.

Mobilizing for change

Rodriguez is a part of the organizing group Youth United for Change. Last summer and into the fall, YUC did some surveying of its own: administering hundreds of health questionnaires across high schools and asking classmates what they most want to see improved. Because mental health services ranked among the priorities — along with school food and building conditions — the group developed a campaign to push the district to respond better to student trauma and stress.

And all of that led her to City Hall where Rodriguez, backed by fellow YUC members, addressed Philadelphia City Council members at a Wednesday hearing on the school district budget.

She asked the two council members present to consider school “care rooms,” where students can relax if they are feeling overwhelmed, as well as a limit of two tests a day. She also urged officials to require teachers and counselors be trained in trauma-informed care.

Research suggests that between half and two-thirds of all school-aged children experience trauma, and it is common among Philadelphia’s young people. One study found that 88 percent of urban middle school students had witnessed a robbery, assault or homicide, and 67 percent had been a victim of violence.

School district officials say they’re working on it.

Karyn Lynch, chief of the district’s student support services, said she recognizes that trauma has an enormous effect on students’ stress and performance.

“It impacts all of the skills you need to sit in a classroom throughout the day and experience an educational and instructional process,” she said.

Lynch said the district is already taking a trauma-informed approach to training teachers, counselors, and even school police officers. It has also hired a director of trauma-informed practices. Next year, the district will begin offering a “Trauma 101” course at nine schools for teachers and staff through a partnership with United Way.

In its most recent push to respond to mental health needs, the district partnered with the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services to implement the Philadelphia Support Team for Education Program (STEP). Community Behavioral Health, the nonprofit that runs most of the city’s behavioral health programming, has directed $1.2 million toward the first phase of the program — hiring social workers for 22 schools. Central High School, where Rodriguez goes, is not one of them.

In all high schools, even where there are no clinical mental health resources, there is at least one counselor. A 2015 analysis by the website the 74 million found that Philadelphia employs more police officers than counselors. And Rodriguez said that the counselor at her school is not advertised as a mental health resource. In fact, she told City Council, most of her friends only visit their counselors to get SAT test fee waivers, a dynamic she said demonstrates that testing culture takes priority over mental health culture.

Plus, she said, it’s not exactly popular to ask for help with managing stress.

“There’s still this stigma about going to the counselor, and asking for these resources,” she said.

Before the STEP program, the district primarily relied on school counselors and School Therapeutic Services (STS) for behavioral health services. STS contracted with outside behavioral health nonprofits to provide counseling to students and families as needed in about 100 elementary and middle schools. Lynch said although STS will continue, the STEP program was developed when Superintendent Dr. William Hite recognized that STS wasn’t doing enough to meet the needs of Philadelphia’s students. In its upcoming STEP phases, the district plans to hire additional staff to support the social workers.

Until then, Rodriguez and her fellow YUC members remain frustrated. They emphasized that what they’re asking for is an overall culture change.

“Mental health, it isn’t just like a one-time thing, or an initiative, or one big project. It has to be a daily thing,” Rodriguez said. She stressed that facilitating trusting relationships between staff and students would be a good place to start, so students feel more comfortable and valued at school.

“Just having regular conversations — just saying hi and then addressing you by your name,” she said. “That really helps in the day.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.