Bullying and bemusement: Tackling modern politics in the modern classroom

Listen

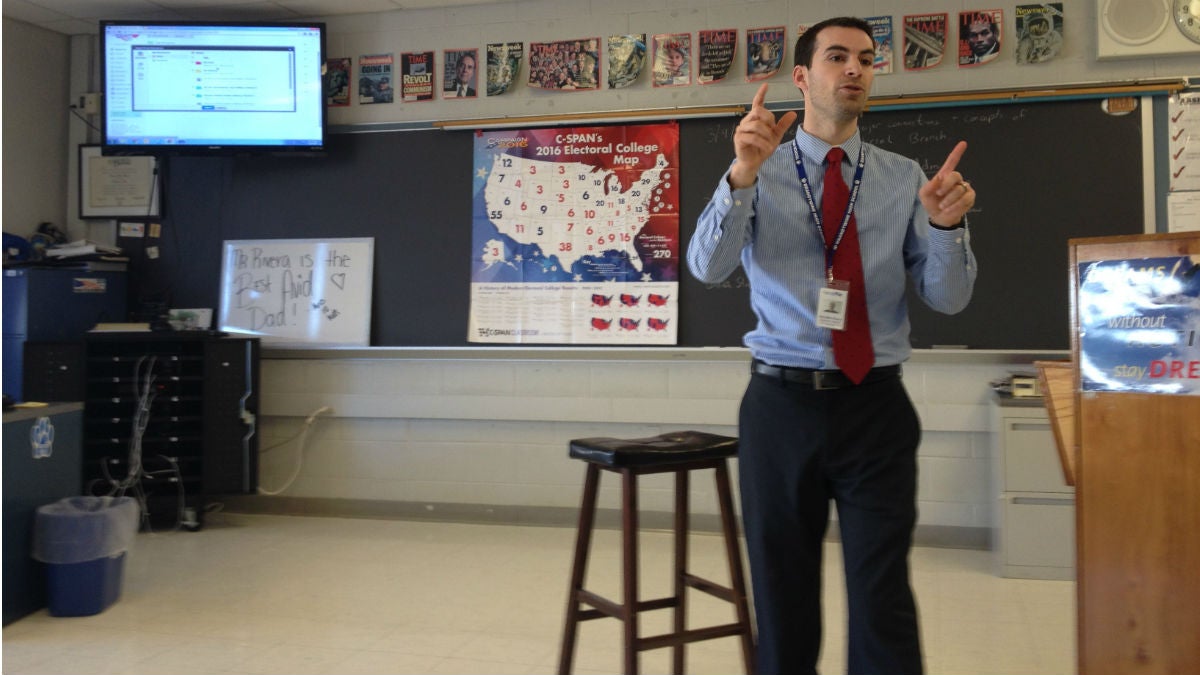

Kenny Rivera

What’s it like to talk about this brutal presidential campaign in today’s sensitive schools?

I haven’t walked more than 10 steps into Brandywine High School in North Wilmington when I spot four pamphlets on bullying. There’s one on cyberbullying and how it’s “seriously wrong.” Another instructs teachers on how to create a “bullying-free school.” A third guide, titled “10 Tips to Help Stop Bullying,” urges adults to “Set the example! Treat everyone — including your child — with respect.”

So it’s a little odd when, less than a half-hour later. I’m in Kenny Rivera’s advanced placement government class watching Donald Trump give his infamous “blood coming out of her wherever” account. And given the content of those prominently placed pamphlets, it’s also a little odd to hear the response from 10 high school seniors watching the video: laughter.

Delaware has passed three anti-bullying laws in the past four years. A fourth is currently before the General Assembly. Since 2008, states have enacted 204 laws related to bullying, harassment, and intimidation in schools, according to the National Conference of State Legislators. Across the country, anti-bullying sentiment permeates every corner of education — from official policy down to classroom practice.

Now contrast that with the tone of this year’s presidential campaign, which has been undeniably nasty. Some have even wondered aloud whether the candidates are modeling the exact type of behavior schools want to discourage.

Rivera wants to confront that notion head on. He’s told his students to bring in examples of bullying on the campaign trail. For 10 minutes, he and his class sit through a montage of brutal political confrontations. Much of it elicits laughter.

‘Why is this happening?’

When the lights flip back on, Rivera turns serious.

“Why is this happening,” he asks the class.

“It’s not presidential. It goes against the policies on bullying and everything else that we want them promoting and passing, then why is this happening?”

The students know why.

“I don’t watch watch political candidate commercials. I’ll shut ‘em off right away,” says Alicia Corrado. “But if they’re like negative ones, they’re kinda funny. They hold your attention.”

Miguel Fuentes agrees.

“We’re all really ready to say it’s hypocritical, it’s silly, they shouldn’t be doing it, it’s childish,” says Fuentes. “But then, while they were playing a second ago, we were all laughing.”

Rivera goes on to cite studies on the effectiveness of political attacks. He notes that Republican voter turnout is up this primary, evidence that some of these tactics have fostered political engagement.

He doesn’t wag his finger at the candidates or sermonize about the evils of bullying. Instead, he leads a candid, lively conversation, never once shying from the crassness of this election season.

“My belief is here I’m dealing with mainly 18-year-old students who need to learn how to have these discussions,” River says.

And the students seem to expect — even crave — straight talk from their teacher.

“A lot of the people I’ve talked to about political correctness are against it. They think people should speak their minds,” says Ben Pradell. “Not everything is an easy conversation to have. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have it whatsoever.”

This political season has spawned a lot of hand-wringing about the campaign’s effect on youngsters. Some of that concern may well be justified. A recent study out of the University of Michigan suggests young adults are more readily swayed by violent political rhetoric than their elders.

But when I asked teachers and students about the 2016 campaign, I found no appetite for misdirection. And when I observed teachers and students discussing politics, I found none of the hemming or hawing I expected given modern sensitivities around bullying.

“There’s really nothing I would say I would shy away from even in the tone of the campaign now,” says Gary Block, an AP government teacher at A.I. duPont High School just outside Wilmington. “Anything that they’re talking about at a debate is worthwhile to bring into my government class and get their reactions to and help them to learn from that.”

Block’s students, like Rivera’s, are eager to talk about this political campaign in particular. These children of the anti-bullying generation are not repulsed by today’s discourse. Far from it — it seems to have energized them, even titillated them to a degree.

“It’s like a reality TV show,” says Nayah Wilson, one of Block’s students at A.I. duPont. “Like you love to hate it. It’s like watching ‘Real World Washington, D.C.’ Like you love it, but you also would never trust any of them to do anything.

“Like when you watch those TV shows, you’re like, I wouldn’t give them a plant to take care of. They’re a mess. But you can’t stop watching. It’s like a trainwreck.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that youth voter turnout has been hearteningly high so far this primary season.

Another view

Mark Overly, however, finds it hard to share in the enthusiasm.

Unlike Rivera and Block, Overly’s charges aren’t yet voter age. He’s the principal at Carrcroft Elementary, a K-5 school in North Wilmington.

Carrcroft takes bullying seriously. There are anti-bullying signs posted around the building, including one right beside the door where students exit for the day. The school has a special box where students can compliment one another or report if they feel threatened. (Overly calls it the “compliment box,” but its purpose, in part, is to root out abusive behavior.)

On a recent Super Tuesday, I saw Carrcroft teachers go through a “mindfulness” training meant to help them better deal with students’ emotions.

After all this conscious effort to eliminate harassment and intimidation, Overly worries the current campaign will undermine his school’s message.

“It’s a shame kids are turning this on, and we’re really trying to teach them how to get along,” Overly says.

So far, Overly says, the presidential race hasn’t been a big topic among students. But he thinks that will change.

Every election year, Carrcroft holds mock campaigns around the time of the general election to teach the students about civics. In the upper grades, youngsters even research the candidates and present on their findings. Overly doesn’t know how exactly the school will handle that tradition this time around.

“I’ll be honest with you, it’s a little scary almost to bring it up right now because I’d be afraid for kids to kinda see some of the slandering and just some of the awful things that the candidates are saying to each other,” Overly says.

He still believes the mock election will go on as planned. But he knows it may get tricky, particularly if, as he put it, “certain people are representing different parties.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.