Staff, students at Philly ‘access centers’ juggle academic needs with COVID concerns

As Philly begins offering in-person classes, city-run access centers provide a glimpse into what it takes to bring students together during the pandemic.

Listen 2:15

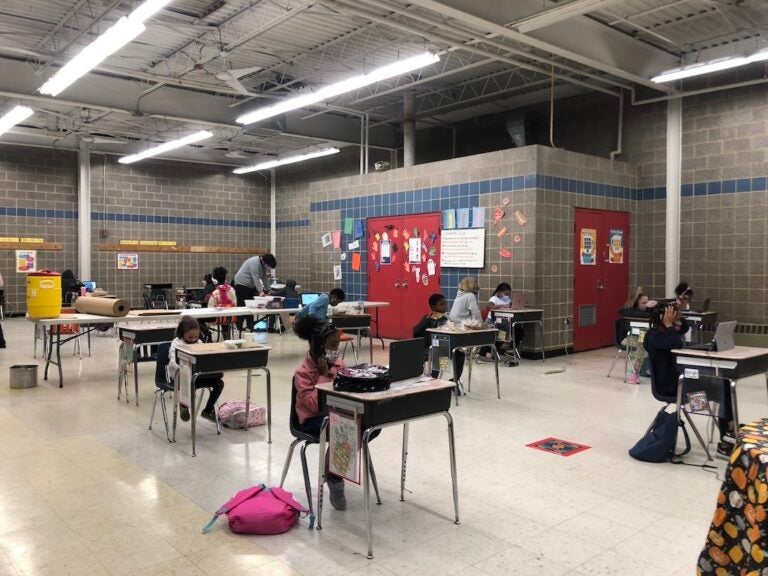

Students are socially distanced while attending class virtually at Vogt Access Center. (Emily Rizzo for WHYY)

Bellowing calls of “Mask on!” reverberate through the rooms of Vogt Recreation Center in Tacony, one of 77 Philadelphia access centers serving as a safe space where children with working parents can log on to virtual school.

With 44 K-6 kids to watch over at Vogt, the anxiety of COVID-19 spread is tangible. Staff constantly remind students to pull their masks up over their noses.

“[The students] don’t want to wear a mask,” said Debbie Darroyo, Vogt’s recreation leader.

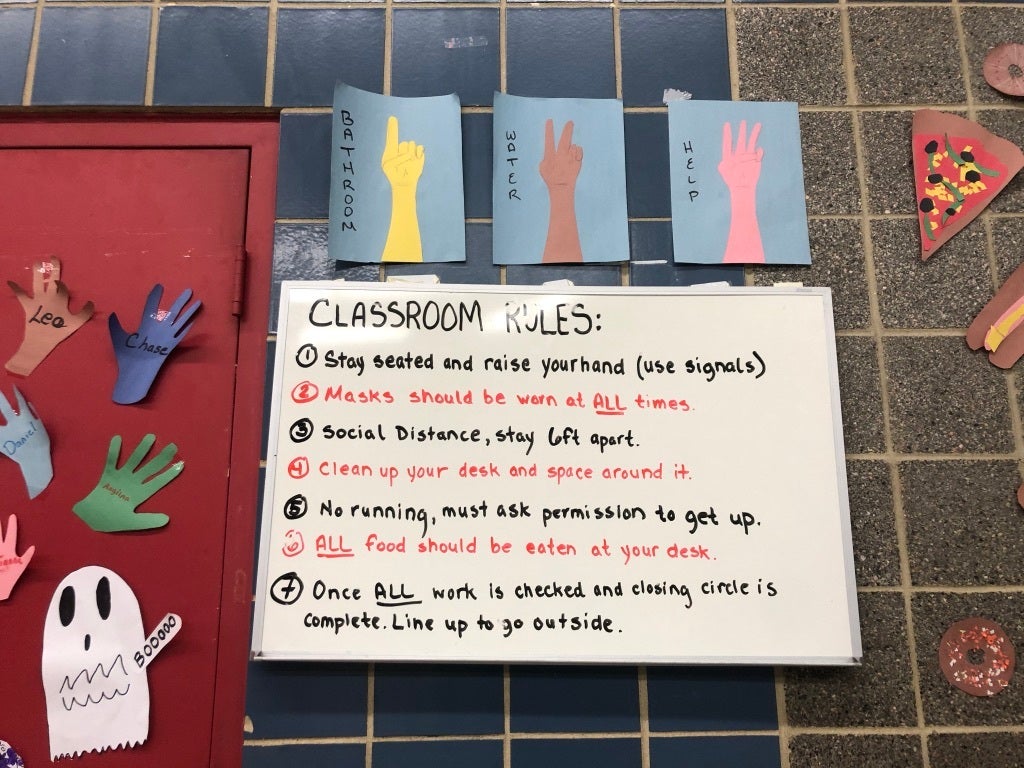

The access centers, which have 2,105 students enrolled citywide, are supposed to follow safety guidelines set by the Department of Public Health. Staffers should take everyone’s temperatures, administer symptom questionnaires, and regularly sanitize surfaces. All students are to sit at least six feet apart.

Even with these procedures in place, Darroyo knows there’s a lot she can’t control. She’s been trying to keep her personal immunity up by eating well and exercising, just in case there’s an outbreak.

“[The students] go away from here and I don’t know who they’re with. They might be away in the weekend, they might go to a state where they’re not supposed to be. I don’t know that,” Darroyo said.

With the School District of Philadelphia set to begin offering some in-person classes after Thanksgiving, these city-run access centers provide a glimpse into how staff and families have been navigating bringing students together during the pandemic.

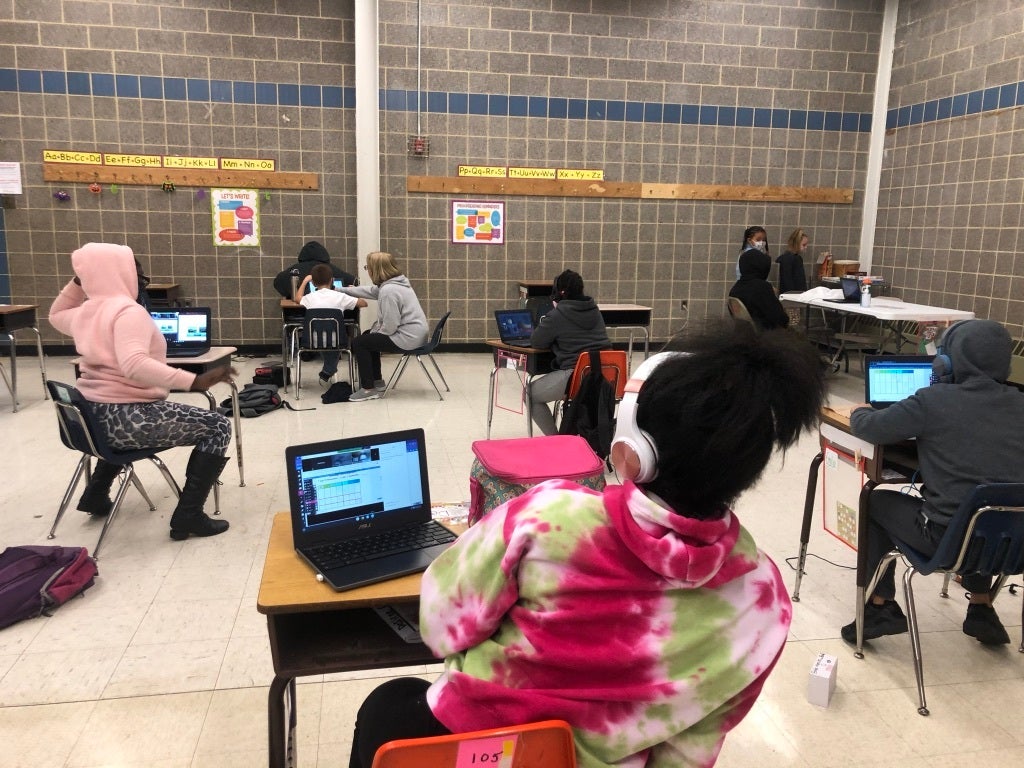

On a recent Tuesday, inside one of Vogt’s two makeshift classrooms, an echoey gymnasium, students sat at their desks nodding to their teachers on the computer screen, their headphones sometimes drooping off.

Staff roamed the aisles, leaning in to assist students when needed and playing games with them during intermittent breaks.

At Vogt, students attend eight different schools, and are on eight different virtual schedules. Any time between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m., some students are in class, while other students, right beside them, are on their lunch break, proudly swinging their sandwiches in the air.

Access center staffers are tasked with learning these schedules, to assure that students don’t miss class time.

Some say, especially in the first few weeks of the year, some virtual teachers weren’t patient enough with students at the access centers. Kids would be marked absent if they dropped zoom calls because of connection issues.

“I would take that personally,” said Kevin Forbes, site director for CORA, which contracts with the city to aid instruction at some access centers, “because that’s not fair.”

‘Making sure they’re emotionally ok’

Stacy Leonard, the managing director of community services for CORA, understands the severity of COVID and dealt with the stress while helping run city summer camps this summer.

“I lost a lot of sleep,” she said.

Leonard and her family contracted the virus in March. “It really takes a hold of you,” she said. “The lasting impact continues to motivate me to ensure that our staff are taking all precautions.”

“We have to just keep reminding them to wear masks,” she said, “It’s like reminding kids in the winter to put their coats on when they go out to play. It happens all the time.”

Within two months, one city access center closed due to a COVID-19 infection. Simons Recreation Center in West Oak Lane was shut down for two weeks in mid-September, just 11 days after opening, after at least one person tested positive. Staff, students and family members were asked to quarantine for two weeks, according to the Philadelphia Office of Child and Family Services.

On top of pandemic concerns, Vogt center staff have to juggle multiple roles for the students: teacher’s assistant, tech help, emotional caretaker.

The kids just “need,” said Darroyo. The K-6 students have a wide range of difficulties. Darroyo pointed to one kindergartener, the youngest in the room, who cries in the morning because she misses her mother.

Forbes, of CORA, views it as his responsibility to ease their stress. “That’s what we’re here for,” he said, “It’s a lot of work for them, so we’re just making sure they’re emotionally ok.”

Navigating online school comes with a learning curve for students who are trying to adapt to staring into screens for hours a day and adjusting to new classroom rules and dynamics.

For example, at Vogt, students hold up hand signals to communicate to staff, so as not to disturb their classmates. One means bathroom, two means water, three means help.

Leo Hernandez, 9, was previously doing virtual school at his kitchen table in Wissinoming. He’s happy to have his own desk at the rec center, but can be distracted by the other students in the room.

“Sometimes they scream while someone else is in class and then you can hear them through the headphones,” said Leo.

Examples like this tap into concerns that pandemic-era schooling is widening inequities between students. Students at access centers may have a leg up on those trying to learn at home in worse conditions, but many other students from wealthier families don’t need to worry at all about the obstacles students learning in rec centers face.

Some wealthier school districts have been able to return to a more normal schooling routine by hiring additional staff and ensuring safety protocols. Some families in virtual districts have been able to afford personal tutors, or have found flexibility to collaborate with other parents to form pandemic pods, sharing the load of child oversight while offering kids more socialization.

Still, some students at access centers have found ways to benefit from the new classroom setup. Norman Hill’s son, Michael, who has autism, does his virtual school at Simpson Recreation Center in Frankford. Michael says he can focus more than he did at in-person school, partly because of the smaller class sizes.

Hill hopes the district doesn’t send his son back to his regular in-person school.

“He’s not getting irritated as much, he’s getting school work done. The access centers have been a great help,” said Hill.

Like Michael, Faith Allen, 10, has embraced her access center. Her grades are mostly As and she said she gets a lot of help from the Vogt staff.

Allen does miss being around her typical classmates, though. “The social aspect is hard,” she said. “Since corona happened, I would really like to go back to school.”

Forbes said that’s exactly what inspires Vogt staff. Along with helping parents, they want to provide kids a sense of normalcy and more social interaction than they would get at home.

Working single parents, like Kyree Robinson, are grateful for the extra help. Robinson missed work to watch his 8-year-old son, Syire, during virtual school in the spring. Once Syire started at Simpson Rec, he was able to refocus on his two jobs.

“At the end of the day we have to provide for our family, because, as you know, the world and the pandemic [are] still moving on. Bills still have to get paid,” said Robinson.

Many other Philly families are hoping to benefit from the access centers eventually. There are currently 484 students on the waiting list.

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)