This immersive sound installation brings you inside the Schuylkill River

A rushing river is a familiar sound. But underwater, there’s a whole other sonic world — where insects drum, fish click, and bubbles burst.

Listen 1:47

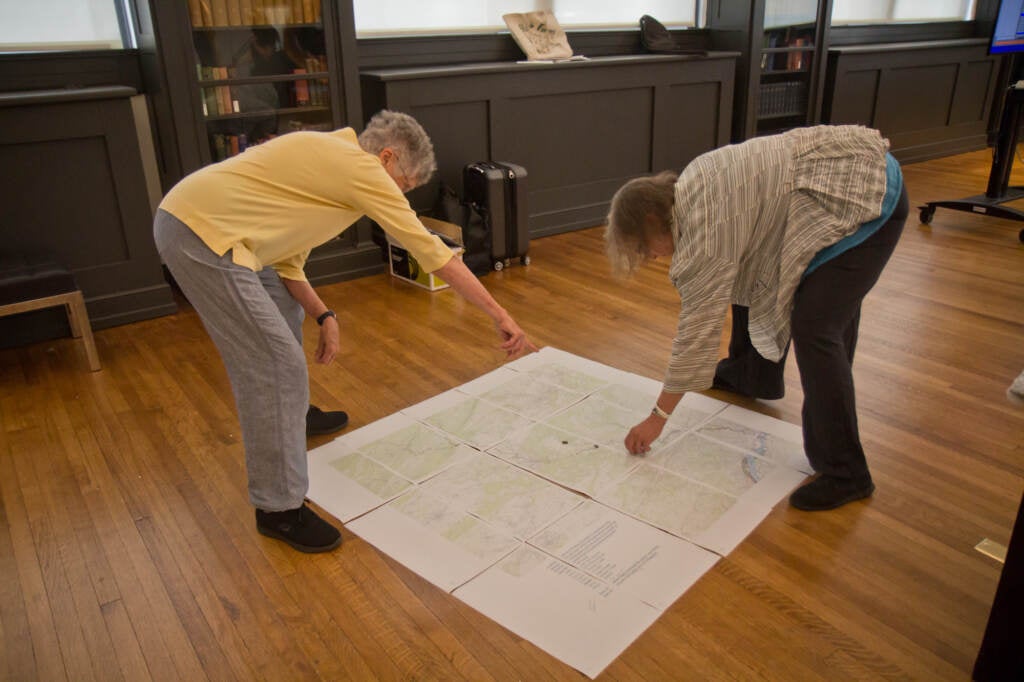

Artists Annea Lockwood (front) and Liz Philips (back), listen to sounds they recorded along the Schuylkill River watershed through wood, at their exhibit, The River Feeds Back, at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

A rushing river is a familiar sound. But underwater, there’s a whole other sonic world — where insects drum, fish click, and bubbles burst.

The River Feeds Back, a new installation opening Wednesday at Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences, takes you there. It’s an immersive sound experience of the Schuylkill River.

“It’s really a tracing of the river’s course through all sorts of terrain … and listening to how the river changes,” said New York-based composer Annea Lockwood, one of the artists behind the exhibit.

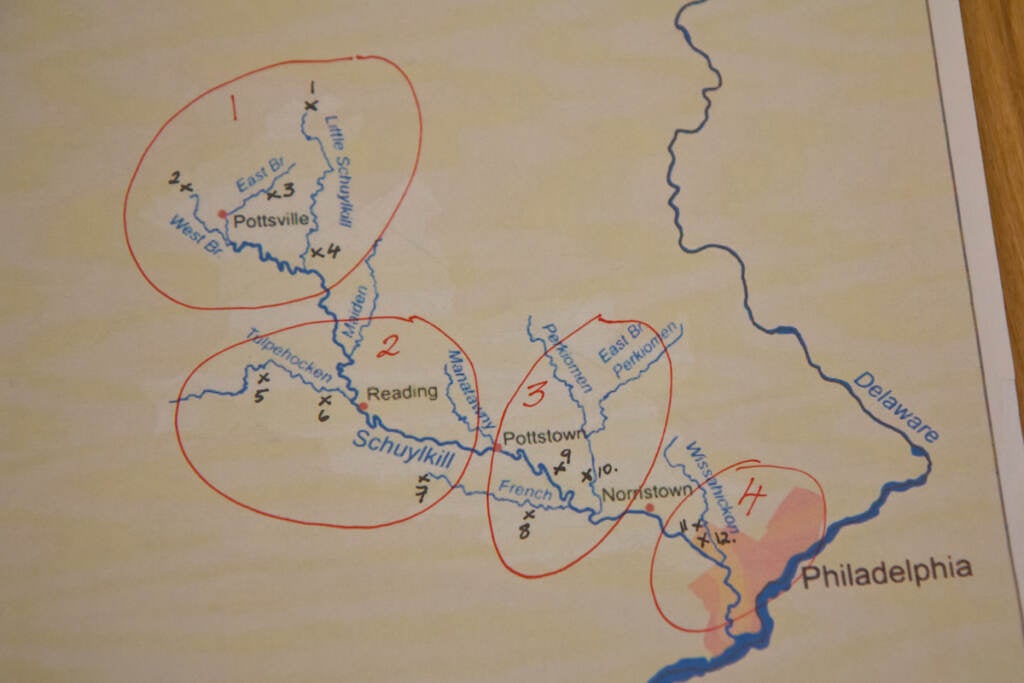

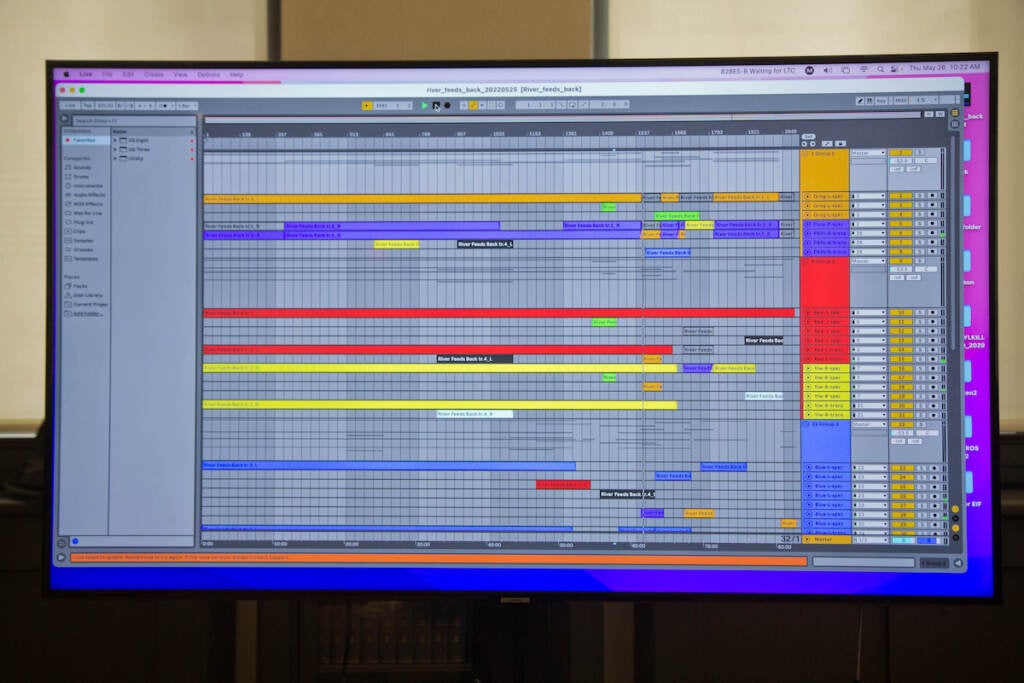

Nature sounds recorded at 19 spots along more than a hundred miles of the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania play from a series of sculptures, or “listening portals,” arranged in the Academy’s resonant Dietrich Gallery. The installation is part of the Academy’s “Water Year” initiative, designed to connect people with their local watershed and the need to protect it.

Rushing and gurgling water, chirping insects, and squawking geese paint a sonic picture of a river coming alive in spring. Some parts of the composition, like a distant train, are relaxing, and others, like a jubilant chorus of spring peepers, will wake you up.

Then, there are the otherworldly sounds the artists recorded underwater, using hydrophones: bubbles rising from the riverbed.

“It’s a whole different environment,” said Queens-based multimedia installation artist Liz Phillips, co-creator of the exhibit. “It’s like going to outer space, practically, for your ears.”

The artists use a variety of objects to project, reflect and radiate the sound. Some, like a piece of driftwood found bobbing on the river, were gathered. Others, like a paper-mache snake and egg, were made.

“We play back through them,” Phillips said. “They become some of our speakers.”

The whole composition is 82 minutes, but you’re not expected to stay for the whole thing.

If you sit down on a natural wooden bench in the exhibit, you might be surprised to feel the sounds of the river piped through the wood.

“You’re sitting on a bench just thinking, Oh, it’s a convenient place to sit and listen,” Lockwood said. “And all of a sudden, you’re vibrating!”

Feeling close to the river is the point. Lockwood hopes the experience will get people more interested in conservation.

“If you really immerse yourself, I think you experience what I call non-separation, that we’re not separate from all the elements of the environment around us,” she said. “We are deeply integrated. And the more deeply integrated we feel, the more care we take.”

The River Feeds Back is open at the Academy of Natural Sciences through the end of October.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.