Some shuttered schools experience rebirth

Editor’s Note: PlanPhilly partnered with the Philadelphia Public School Notebook to produce a February edition focusing on school facilities. With declining enrollment and 70,000 empty seats, it is likely that some schools will be closed.

By JoAnn Greco

For PlanPhilly

Yellow heart pine floors stretch across apartments filled with architectural details like oversized windows, beamed ceilings, and detailed wainscoting. On the roof, a sprawling deck offers perfect views of Center City, while downstairs, a rec room and fitness facility await the condo owner at Hawthorne Lofts, 12th and Fitzwater Streets.

Not long ago, though, this was just another empty building – the Nathaniel Hawthorne School, built in 1909, entered on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and long since closed – set amidst the ragged debris of a neighborhood in transition.

As District officials deal with 70,000 empty seats and review schools for potential closure, the question of how and whether to reuse shuttered buildings will have great impact on the physical face of the city, says Gary Jastrzab, executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

From a planning perspective, this “is about as exciting as we can hope for,” he said. “There are great opportunities to serve the neighborhood in ways – from housing developments to charter schools to co-located municipal facilities – that offset some of the anger and disappointment associated with a school closing.”

The development of Hawthorne Lofts came at a critical point in the neighborhood’s hoped-for revitalization. The Martin Luther King towers had been imploded in favor of townhouse-style affordable housing, and the next-door Bella Vista neighborhood was enjoying record real estate prices. The area, called Hawthorne, seemed ripe for redevelopment.

Tony Rufo knew that. After inheriting some family homes, he set off on a career of buying and renovating others in the neighborhood. All along, he says, “the school was in my wake.” Closed since the 1980s, the building was never fully redeveloped by subsequent buyers. When it was again offered for sale, Rufo pounced. A few months ago, the Conshohocken-based builder and developer completed the conversion into 53 loft-style apartments sporting granite countertops and stainless steel kitchens.

It was costly, he said, “but it’s such a beautiful old building, with thick walls, huge windows, and a great exterior.” So far, about a third of the units have sold; asking prices range from $160,000 to $340,000.

But luxury condos may not be the preferred use in every neighborhood. “There are only so many” that can be built in the city, noted School District Deputy Superintendent Leroy Nunery.

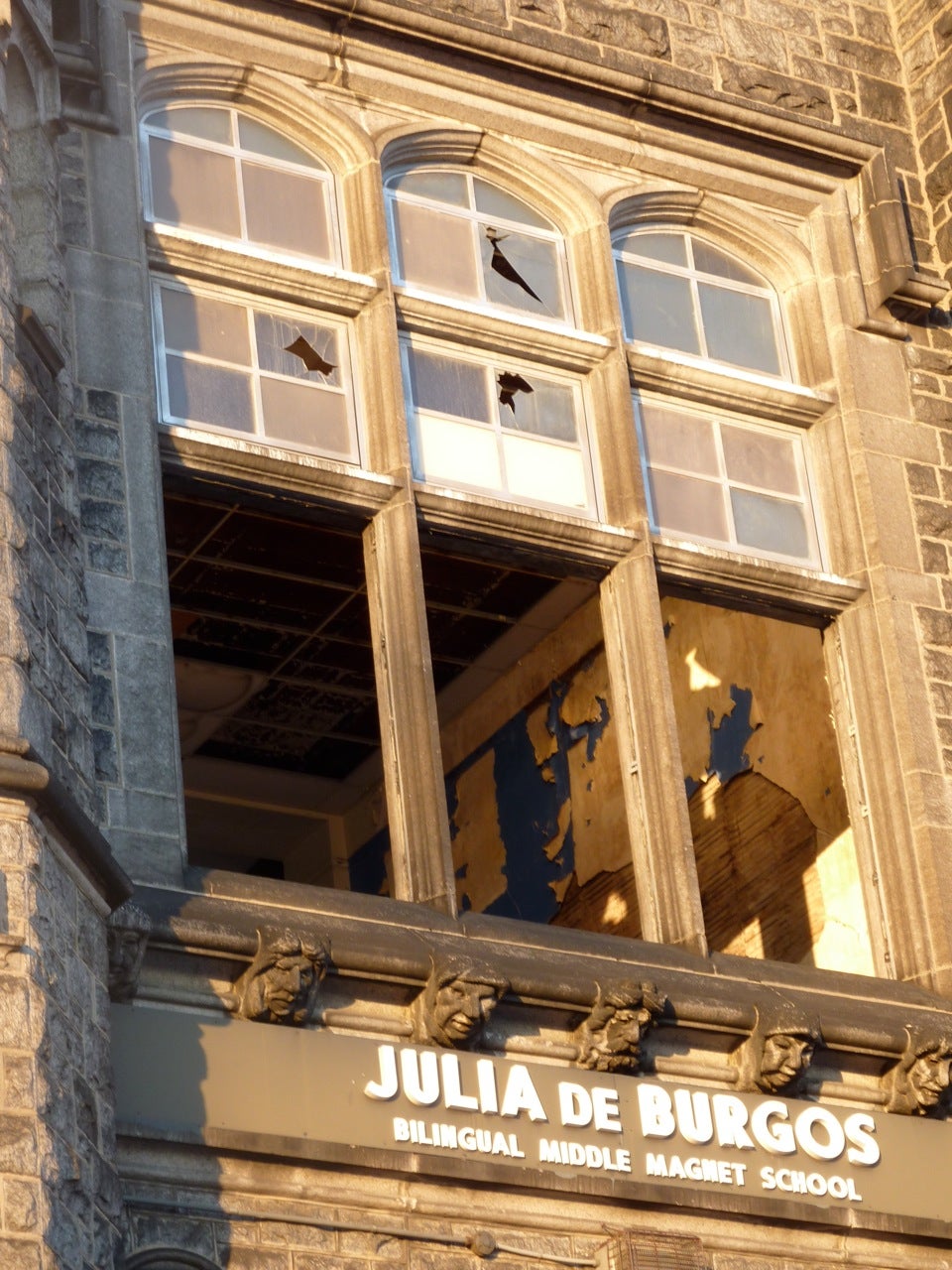

As a prime example, a few miles north, at 8th and Lehigh, stands a compelling, 19th-century fortress that features crenellated towers and a coterie of gargoyles. The original Northeast High School, then Thomas A. Edison High and finally Julia de Burgos Middle School until 2003, the structure is under agreement of sale for $600,000 to Mosaic Development Partners LLC, which specializes in projects designed to revitalize struggling communities.

Mosaic told the City Planning Commission it will demolish the original part of the school to make room for a supermarket and put senior housing in a newer section of the building. For now, though, the site is awash in a sea of discarded tires and newspapers, covered in graffiti and sporting smashed-out windows. “These buildings are often icons in their neighborhoods,” observed architect Joseph Denegre, principal at the Center City firm CDA&I, which has helped update more than 30 District schools. “But, at the same time, they become symbolic of the neglect that those neighborhoods have suffered.”

Although the Edison/deBurgos site might be reborn, buildings like it present “the hard reality that it can be very difficult to find a new use for them, except for housing,” Denegre said. “And unfortunately that use is subject to market forces.”

Regardless of location, the buildings shouldn’t be written off, emphasized Jastrzab. He cites an award-winning 1990 conversion of the Thomas Dunlap School, a stately stone building at 51st and Race Streets. The District transferred the property to the Sanctuary Church of the Open Door for a token fee. After consulting with the community and local real estate experts, the owners decided that affordable senior housing was most needed. Today, The Dunlap Apartments offer 35 one-bedroom units, fitting right into the primarily residential neighborhood.

Jastrzab also sees potential as city government works to “right-size” its own capital inventory, which could, he says, involve the demolition of obsolete municipal buildings. “Wouldn’t it be great if we could co-locate, say, a library, rec center, and health center in one building?” he asked. School buildings are often a core component of a neighborhood’s urban fabric, he pointed out, and residents already rely on them for everything from attending community meetings to casting votes.

Still, demolition is sometimes the best solution, which is the plan for the vacant Wanamaker Middle School, a low-rise brick and granite 1950s structure.

A local planning firm, WRT, originally intended to incorporate the building into its concept for a new mixed-use project at the corner of Cecil B. Moore Avenue and 11th Street. But after evaluating the structure, including its hazardous materials, “the more it began to make sense to demolish,” said Gil Rosenthal, principal at WRT. “It was hard to find uses for the school’s huge spaces, like the theater and the gym. The question for the developers became, is it worth the cost of the renovations?”

With their meandering layouts, extra-wide hallways, and specially delineated spaces, school buildings can indeed be odd ducks. Often a charter school is the only venue even interested.

That’s fine with Nunery, who said that when and if the time comes to put school buildings on the market, the intent is not to “flip” them to the highest bidder, but to “go to the educational options first.”

Sometimes, though, developers and educators do fight over a desirable building. In 2006, a charter school engaged in a bitter bidding war with a condo developer for a 1911 school building at 16th and Lombard Streets. Though outbid, Independence Charter School eventually won the building by paying the higher price ($6 million) to the developer, Miles & Generalis, who decided to forgo its plans in the face of neighborhood opposition.

“We were furious. There seemed to be no interest in offering a discount to the charter,” said Terry Gillen, a key advisor to Mayor Nutter and a neighborhood ward leader at the time. “But we kept the pressure on because we felt like this neighborhood really needed a school.”

Today, Independence enrolls 770 K-8 students from 46 zip codes. According to CEO Jurate Krokys, the charter’s facilities committee walked through about 20 buildings, including Hawthorne, before discovering that the former Durham Elementary School, vacant for about five years, was on the market.

The charter poured another $11-plus million into the building, Krokys said, including new windows, bathrooms, ramps and an elevator. Painted in vibrant shades of marine blue and lemon yellow, the school’s hallways and classrooms showcase touches like intricate built-in cabinetry and sliding pocket doors. Its corridor floors are laid with black, diamond-shaped concrete slabs, while classrooms gleam with long strips of pine flooring. It is, in short, as perfect an adaptive re-use of a 100-year-old community asset as one could hope for.

“There’s no doubt that these [older] buildings have value,” said Denegre, the architect. ”They’re magnificently built, they have lots of capacity, and they have qualities that today we think of as ‘green,’ like access to public transportation, and natural ventilation, light, and insulation.”

No longer right for the School District? Perhaps not. But with imagination and investment, wholly reinventable.

JoAnn Greco is a contributing writer for PlanPhilly, which partnered with the Notebook on this edition. Contact her at www.joanngreco.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.