Camden schools report signs of improvement

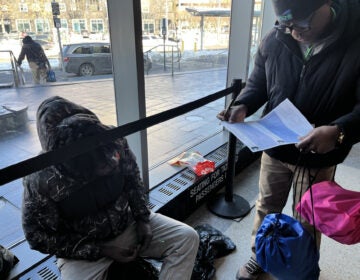

KIPP Cooper Norcross Academy is one of Camden's Renaissance schools. (Alan Tu/WHYY)

As Camden’s schools prepare to begin a fourth year under state control, their superintendent argues that a spate of reforms has begun to improve one of New Jersey’s poorest and lowest-performing districts.

“By almost every measure, our schools are better today than they were three years ago,” Camden Superintendent Paymon Rouhanifard said in an interview. Rouhanifard, who was appointed by Gov. Chris Christie in 2013, said the graduation rate has risen substantially, more children are enrolled in pre-K, and internal surveys show students feel safer in their schools.

But those encouraging facts notwithstanding, average test scores at regular public schools in Camden remain at the bottom compared with other districts statewide. It’s also difficult to determine if student learning is starting to improve because the state’s new PARCC exams are not directly comparable with the NJASK and HSPA tests they replaced. And the hybrid schools, called Renaissance schools, are so new that there is very little state data on their students’ performance.

In a sense, Camden is in the early stage of an educational experiment. The release of a second year of PARCC results this fall may provide some clarity.

The experiment has two main components. One is the state takeover that Christie initiated in 2013, which took away most powers from the elected school board and vested them in Rouhanifard. The other is the opening of Renaissance schools, as permitted by the Urban Hope Act of 2012. The schools were authorized in three cities — Camden, Jersey City, and Newark — where large proportions of students fail statewide exams, but they have only opened in Camden.

Unlike the city’s older charter schools, which are directly authorized and overseen by the state Department of Education, Renaissance schools operate under contracts approved by the Camden school board. They are run by nonprofit organizations rather than the superintendent, but they are accountable to the district and, like traditional public schools, they largely enroll children from their own neighborhoods.

There are seven Renaissance schools in Camden that enrolled 2,190 students last year, or about 14 percent of the city’s public-school children. They are operated by the Mastery, Uncommon, and KIPP charter school networks. Two more schools will open this fall. Those nonprofits have contracts allowing them to enroll over 9,000 students, meaning they could eventually accommodate more than half of Camden’s approximately 16,000 schoolchildren.

The district also has 21 traditional public schools, with 9,300 or 58 percent of students. There are nine charter schools with 4,490 kids, representing 28 percent of students.

Given the uncertainty about how Camden students are faring, much of the debate over the district’s direction has focused on the merits of the state takeover and the move to a public-private model. Local activists angrily protest the loss of sovereignty, and some education experts criticize the Renaissance model for allegedly treating children harshly in some schools and excluding the neediest students.

Superintendent Rouhanifard says he sympathizes with concerns about local control, but defends the Renaissance schools and state intervention as desperately needed opportunities for a hard-hit community whose school district has been an abject failure for decades.

A long way to go

One of the most striking changes since the state intervention has been the increase in the graduation rate, which climbed 15 points to 64 percent over three years, according to the district. Another is a jump in enrollment of 3- and 4-year-olds in state-funded pre-K, which should boost students’ future success in elementary school. Pre-K enrollment is up 20 percent, and is approaching 100 percent of the district’s target.

Rouhanifard also touts internal surveys that show students feel safer in their schools and a much higher percentage of teachers in regular district schools “feel supported” by the central office.

“We still have a great, great deal of work to do, and we have the challenges we inherited, decades in the making, with poverty and racism at the root of it. But we’re really hopeful and optimistic because of the progress we’ve seen,” Rouhanifard said.

The Renaissance schools have also released a few bits of encouraging internal testing results from 2014-2015, their first year of operation.

For example, KIPP Cooper Norcross Academy reported that, on average, its kindergartners rose from the 25th percentile in math to the 68th percentile nationally over the course of that year. In reading they moved from the 37th to the 63rd percentile, according to KIPP’s annual report to the state. No results were released for students in other grades.

Uncommon Schools said 90 percent of its kindergarteners hit proficiency benchmarks in reading by the end of the year, up from 19 percent at the start, and math proficiency increased from 36 percent to 84 percent. Mastery, which runs five schools, reported improved reading skills for grades K-3.

The district has also touted a smattering of relatively good PARCC results. At Brimm Medical Arts High School, a public magnet school, 93 percent of 11th graders achieved the graduation standard of at least level 3 out of 5 on the language exam, compared to 65 percent statewide. Mastery North Camden, the only Renaissance school that had PARCC-age students in 2014-2015, had the district’s top scores in fourth and fifth grade reading and fifth grade math, though the proficiency rates were still far below state averages.

At Camden’s charter schools, a number of classes performed well compared with the regular public schools, although their test-passing rates were, again, low for New Jersey. For example, at Pride Charter Elementary, 62 percent of fourth graders passed math and 55 percent passed language arts. At ECO Charter, 57 percent of fifth graders and 54 percent of fourth graders passed language arts.

The charter schools have been around for a number of years, some for a decade or more. They are directly chartered by the state, without school board involvement, and operate much like independent private schools, without any supervision by the district or superintendent. Unlike Renaissance and traditional public schools, they do not give priority to neighborhood children.

As for the regular public schools, despite the higher scores at Brimm Medical Arts, PARCC results from 2014-2015 were on the whole among the lowest in the state.

On the language arts exams, a dismal 6 percent of third through eighth graders in the regular district schools met or exceeded expectations, compared with about 50 percent statewide. In math, just 4 percent met the standards. Less than 8 percent of high school students met the standards on language tests and less than 3 percent in math.

Rouhanifard also notes that the graduation rate, though higher now than a few years ago, is still unacceptably low. In addition, those students who do graduate tend to struggle in college, according to local institutions like Rowan University and Camden County College that some of them attend.

“While 15 percentage points is meaningful growth, more than a third of our kids aren’t finishing high school,” Rouhanifard said. “Those that are, are still on average not prepared for that next step in life, whether that’s finding a meaningful career directly out of high school, or attending a two- or four-year institution of higher education.”

Rouhanifard said the district has boosted its graduation rate in large part by pushing high school seniors who did not take or did not pass the standardized graduation exam to submit portfolio appeals. Portfolios use a sample of coursework to demonstrate that the student met the graduation requirements.

Close to half of Camden’s graduating seniors used portfolio appeals in 2014. This year the district had 379 seniors in regular district schools, not including special-education students, and at least 250 have used portfolios, amounting to perhaps two-thirds of all graduates. Rouhanifard and others defend portfolios as a valid alternative for disadvantaged nonwhite students who tend not to do well on standardized tests.

A controversial model

Given the lack of clarity about how Camden students are faring, much of the debate over the district’s direction has focused on the merits of the state takeover and the promotion of privately run Renaissance schools.

As the Renaissance schools expand, and more open in the future, they are expected to attract a larger proportion of the city’s school-age children, depressing enrollment at traditional public schools and possibly at charter schools. With students and district funding increasingly going to Renaissance schools, more public schools are likely to be closed and more unionized teachers and employees could lose their jobs. Renaissance school employees are not members of public school unions.

One frequent critic of the takeover is Camden High teacher Keith Benson, who hasslammed the city and district for ensuring “residents are forbidden from being partners in Camden’s public education system.” Benson calls for a restoration of the school board’s powers, pointing to Brookings Institute report that concludes that “meaningful and authentic community engagement is a prerequisite” for improving struggling schools.

Rouhanifard said he’s very aware of residents’ discontent over having their democratic rights stripped away. He argues the system before “wasn’t doing right by kids” and sometimes prioritized adults’ interests over those of students, resulting in failing schools, dilapidated buildings, financial mismanagement, and other problems. The superintendent has said he would like to see board authority restored in three to seven years; he says it could actually happen in three years if the district improves enough by then.

Another critic is Stephen Danley, an assistant professor of public policy and administration at Rutgers University-Camden and an outspoken blogger. His concerns include complaints about the educational philosophy used by KIPP, Mastery, Uncommon and similar organizations in Camden, Newark, Philadelphia, New York, and other cities. Some of the schools use a “No excuses” model, he says, which emphasizes strict discipline and obedience, and can result in high suspension and attrition rates, particularly of young black males.

He pointed to Success Academy charter network in New York, where some first-grade teachers reportedly rip up student papers or belittle children in front of classmates if they stumble when called upon to answer a question. Students there are rewarded for good behavior with candy and prizes, while infractions bring reprimands, loss of recess time, extra assignments, and suspensions, even for kindergarteners.

Success Academy has said incidents of harsh treatment are anomalies that are not consistent with the school’s policies, and teachers who commit them are reprimanded and undergo retraining.

In some cases Success Academy and other charter schools also seem to be “weeding out” more challenging students, Danley said. Renaissance-type schools in some places have underenrolled low-income children, special-education students, and English language learners, or even favored “reduced-lunch” kids over poorer “free-lunch” kids, with the effect of improving their schools’ test scores and dumping less-well-performing children back into the regular district schools, he said.

Rouhanifard dismissed suggestions that Camden’s Renaissance schools are engaging in such practices. He said the schools’ percentages of particularly challenged kids are for the most part the same or higher than district percentages generally. But Danley says Camden has not shown that the whole effort to replace district staff and programs with an undemocratically imposed, discipline-oriented corporate model of education is worth all the community and school disruption.

“What you’re not seeing is a whole lot of boats uplifted,” he said. “What you’re seeing are hopefully some marginal gains in a very, very difficult situation. And at what cost?”

________________________________________________________

NJ Spotlight, an independent online news service on issues critical to New Jersey, makes its in-depth reporting available to NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.