Seeking accountability, states revise charter school laws

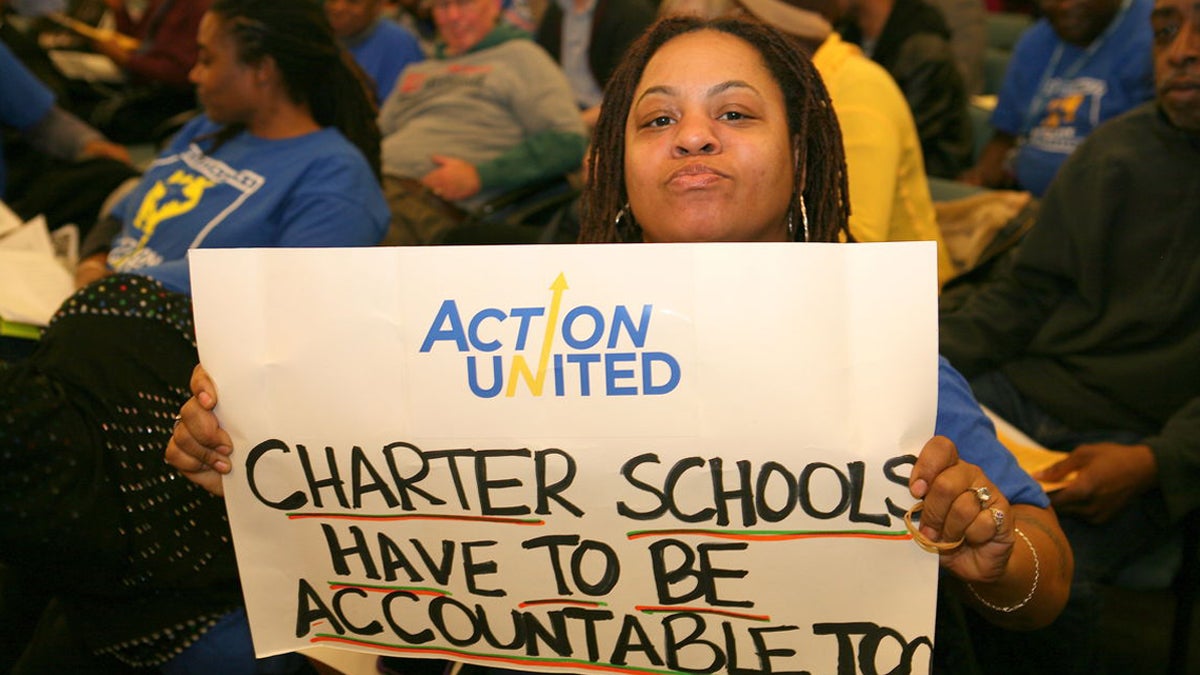

Accountability among charters is of concern to education advocates like Action United member Dawn Hawkins

Pennsylvania has not updated its original 1997 law that allowed the schools’ creation.

Gary Miron, a researcher at Western Michigan University, can still recall the heady early days of the charter school movement, now a quarter-century ago.

“Charter schools were supposed to be small, locally run public schools. They were going to be open to all,” Miron recalled.

“This was a movement to create schools that would be highly accountable to parents and the public. But 20, 25 years later, there are not that many schools left that embody that original intent.”

Accountability now appears to be the issue that states, charter authorizers (such as local school boards), and even advocates are still grappling with.

The stakes — both in terms of student outcomes and public money spent — are exceedingly high. According to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, charters are a multibillion-dollar industry now, with nearly 3 million children enrolled in more than 6,800 charter schools in 42 states and the District of Columbia.

Greg Richmond, president of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA), an advocacy group, made a frank assessment of the national landscape in early May, calling out what he termed “bad actors.”

“We have tolerated bad schools and con artists for too long,” Richmond wrote in an essay in The Huffington Post. “… Some for-profit companies running charters engage in self-serving real estate deals, hide their financial practices from public view, claim they own assets purchased with public monies, and spend large sums to influence state legislators.”

His group, based in Chicago, works with authorizers and states to upgrade practices and strengthen legislation related to opening schools, monitoring performance, and closing schools that chronically fail.

“A lot of states have found that their laws are lacking. They’re old, they’re outdated, they haven’t kept up with modern practices that we know work for charter school accountability and oversight,” said Amanda Fenton, director of state and federal policy for NACSA.

“The goal of the charter movement was never to create more bad schools. We seek to improve authorizer practices and improve state policy,” she said.

A look at the states

More than a dozen states have done “complete overhauls” of their public charter school oversight laws, regulations, and policies over the last six years, Fenton said. Four states — Maine, Mississippi, Alabama, and Washington — are newcomers, having only recently enacted charter school laws. But in Pennsylvania, the charter law was written in 1997 and it hasn’t been updated since then.

“It’s fair to say Pennsylvania is the exception to the rule,” said Todd Ziebarth, senior vice president for state advocacy and support with the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

“In terms of doing a significant overhaul in key areas, around authorizing and accountability and funding and facilities, Pennsylvania has yet to do that.”

Fenton agreed, but added that “several authorizers in Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia School District in particular, have really been trying to step up their game.” In April, the District’s charter school office issued the first of what it said would be annual reports on the academic, financial and organizational health of all charters in the city — a development that drew praise from Fenton.

Philadelphia City Controller Alan Butkovitz has long urged an overhaul of Pennsylvania’s charter law to give local school districts greater oversight and compliance authority.

Washington state’s first effort was ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court last year as being ineligible for tax money. Revised legislation was enacted in April, but it is being challenged. Provisions of note: The law permits no more than 40 charter schools to open over a five-year period and also mandates that an authorizer must deny renewal to any charter school performing in the bottom quartile of all public schools in the state.

Seven states — Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kentucky, West Virginia and Vermont — have not legalized charters, and only about half the states have legalized virtual charter schools.

Late last year, Ohio legislators enacted House Bill 2 in an effort to rein in excesses on the part of charter management companies, which run about half of that state’s charters. The law requires disclosure of academic and financial performance, including public posting of charter board/operator contracts — the kind of transparency that charter critics have clamored for.

Ohio “finally seemed to go in and close all the loopholes,” said Ziebarth. “We are hopeful [the revisions] will push authorizers to do a better job and push schools to do better … and to push authorizers to put some schools out of business.”

But, he added, “It’s one thing to pass a law like that and it’s another to actually implement it well.”

In December, Miron and Bruce Baker, education finance researcher at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, published a paper examining what they called “the business of charter schooling.” The brief, published by the National Education Policy Center, identified policy concerns related to “ways that individuals, companies, and organizations secure financial gain and generate profit by controlling and running charter schools.”

To counter the profiteering, the researchers laid out eight broad recommendations to policymakers, including calling for public scrutiny of large contracts (such as lease and management agreements), expanded financial reporting requirements, and government authorities to maintain control over public lands and facilities.

Miron said that few states are doing a good job with oversight, but he commended Connecticut and Delaware for the work that’s being done in those states.

Connecticut, he said, “requires all charter schools to recruit from all segments of the district. You can’t overlook anybody. You have to actively recruit, and that helps somewhat. You won’t see any for-profit EMOs [education management organizations] operating there.”

“The people at the state Department of Education know the authorizers, know the principals, and can get them on the phone at any time,” he said.

The case is the same in Delaware, he said.

“It’s a small state, everybody knows everybody, and they do good oversight,” Miron said.

Those two states are among “the better-performing states that are closer to the original intent of charter schools.”

In Delaware, four charter schools serving mostly minority students were closed – two for financial mismanagement and two for poor academic performance. And the state has enacted a moratorium on the opening of more charters amid concerns that the number of charters is undermining the regional education system. There are more than a dozen charters in the Wilmington area. The mandate is for the state to develop a strategic plan for charter growth.

Cause for concern

Delaware State Rep. John Kowalko, a vocal critic of charters, said the charter school movement “has sort of missed the mark.” He has supported legislation, so far unsuccessful, to increase audit oversight.

“We’ve had a series of charter schools that have been accused of mismanagement. We have to put an end to that stuff,” Kowalko said. But getting charter reforms passed has proved difficult. Little has been done “to rein in the excesses,” he said, and he blamed charter lobbyists.

“Every day that you walk through that hall, there are lobbyists. They’re the highest profile, and the charter school operators have six or seven of them at their beck and call every day. The public schools have no place in their budgets to hire lobbyists.”

For Kowalko, the issue is the finite amount of funding for public education, even in a state that covers about 60 percent of education costs for both traditional and charter schools, the remainder being funded by local and federal money.

“They all have their finger in the pie, and you expect that, but if that pie is put out there for the kids, I don’t want anybody else’s finger in the pie,” he said.

Editor’s Note: In partnership with Keystone Crossroads, this article was originally published in the Philadelphia Public School Notebook on June 10, 2016.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.