Say yes to the dress, and the vote: Suffrage and style at Brandywine Museum

The Brandywine River Museum presents a visual history of the campaign for women’s voting rights, now celebrating its 100th anniversary.

Listen 1:36

A variety of pins and buttons were used by both sides of the women's suffrage campaign. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Upon entering “Votes for Women: A Visual History” at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, the first thing that commands the visitor’s eye is a display of five purple capes arranged in marching formation.

The capes are century-old artifacts from the National Women’s Party, used in street demonstrations to compel the passing of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

To the modern eye, they may remind the visitor of the iconic caped uniforms of “The Handmaid’s Tale,” a bleak costume adopted by contemporary protesters demonstrating their concerns about the erosion of women’s rights.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” offers exactly the opposite impression of the original intention of those purple capes. “Votes for Women” unpacks the iconography of a nationwide civil rights campaign a century ago, and the visual triggers that would have been potent in that age.

A lot of the potency rests in the dress.

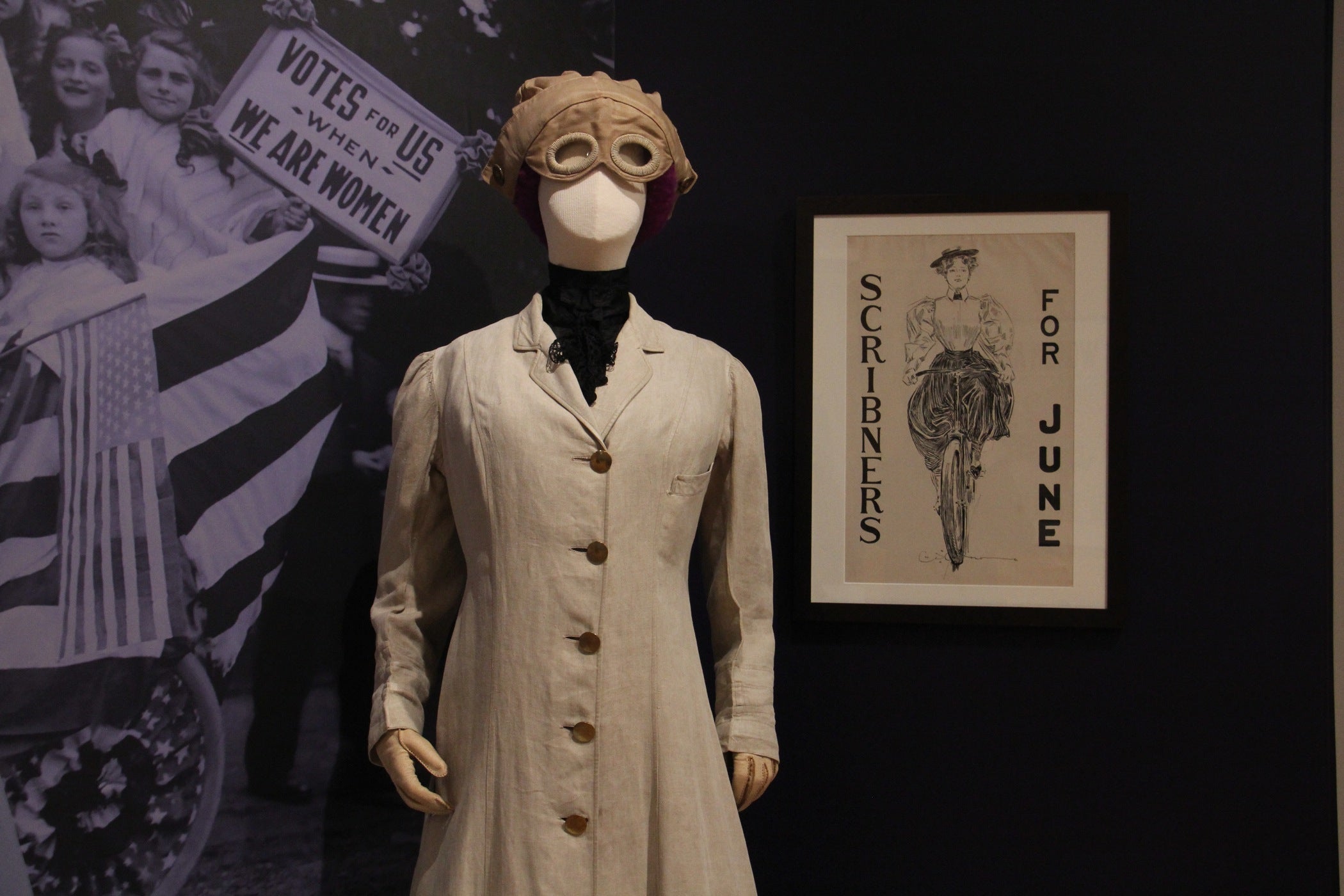

The gallery is ringed by mannequins dressed in fashions of the day. The exhibition focuses on the final decade before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. Though women had been pushing for the right to vote much earlier, the show begins roughly in 1913, when a major contingent of suffragists marched at Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration.

“Women often wore capes, uniforms, costumes to make themselves more visible in public spaces,” said curator Amanda Burdan. “At a parade, wear the party colors of purple and gold and you really got noticed.”

During this era, a younger generation of women ramped up the campaign to push through the 19th Amendment, and they did it with their own, modern visual sensibility.

“‘We’re not getting it done like our mothers and grandmothers. This is the next step,’” said Burdan, articulating that sensibility. “I see it as visibility, making their case and cause in the faces of men who could change the situation.”

That meant putting themselves bodily in public and dressing the part. The clothes on display have higher hemlines — above the ankle, showing off lace-up boots — to better move through the streets without dragging long trains. The looks were tightly tailored, eschewing ruffles and flowing folds of fabric in favor of trim bustlines and cinched waists.

“The styling was a little more military. That’s, of course, because of World War I,” said Burdan. “You see more tailoring, maybe more masculinity in the suiting, instead of lots of laces and frills and flounces.”

The cut of a woman’s dress signaled whether the wearer was progressive or conservative. The dress articulated her politics wordlessly and publicly.

“Dress is used as a metaphor,” said Burdan. “It’s a new generation, a new time: time to change the style and not wear what your grandmother wore and not accept the treatment she accepted.”

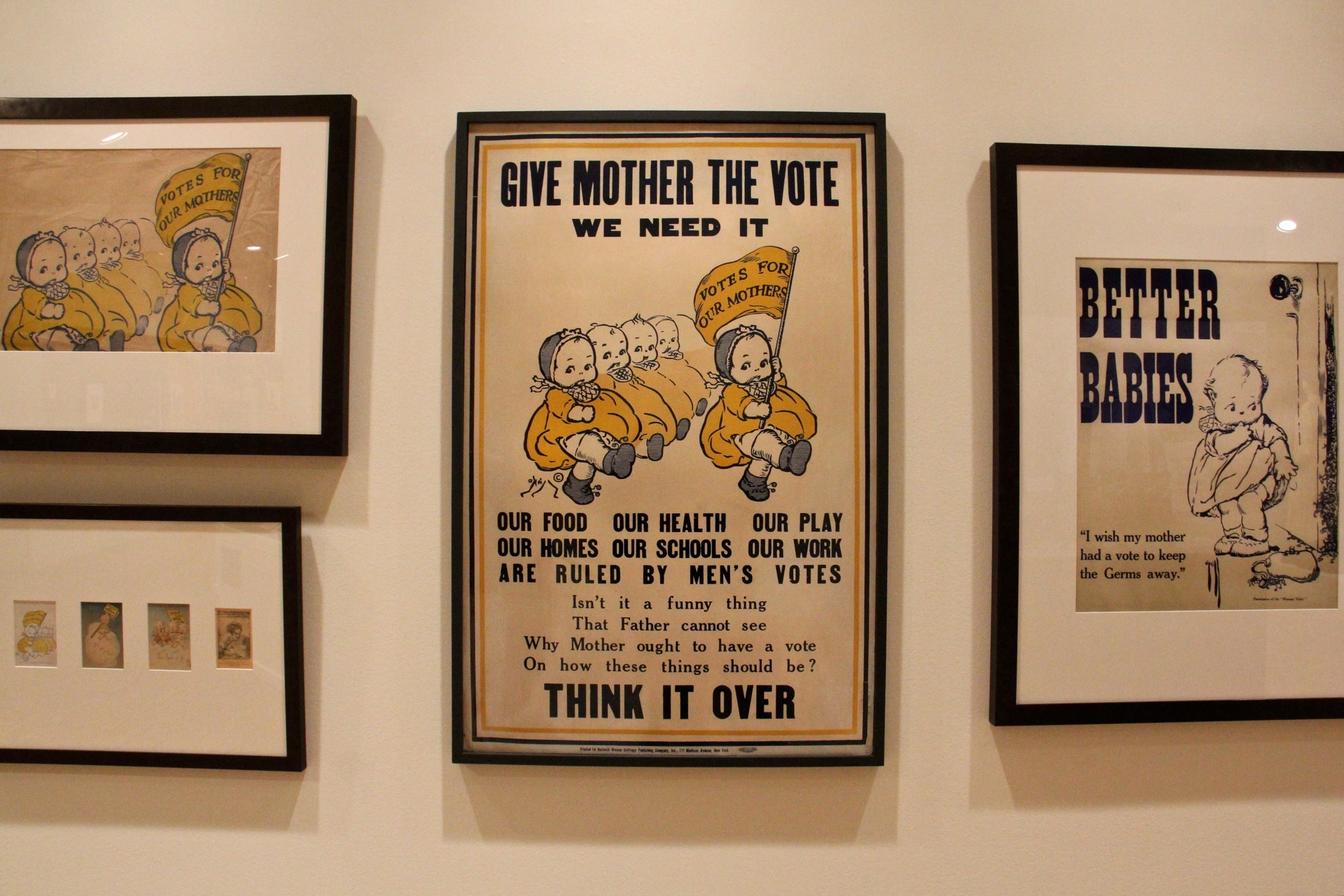

A whole visual language emerged around the campaign for the 19th Amendment. The artist Rose O’Neil made a fortune off her wildly popular creation, the Kewpie Doll, and then leveraged it to further the women’s cause. She created posters and postcards of children with angelic faces insisting their mothers should have the right to vote.

Another prominent artist, Nina Allender, created more than 200 illustrations for The Suffragist, the magazine of activist Alice Paul and the women’s vote movement.

Allender’s political cartoons of the 1910s are filled with symbols that might be lost on the contemporary visitor, like a $36 hat that can be bought on an installment plan. The 19th Amendment needed to be passed by 36 states. A successful national movement had to campaign in each state, one ratification at a time.

One’s style of dress communicates their class standing as well as their political leanings. The clothes on display would have been worn by an upper-class woman who could afford, for example, an outfit to be worn specifically to drive a car, or who could change clothes for indoor political activities versus those outdoors.

There are no clothes on view of someone like a factory worker or a housewife without the means to organize or march. That is due, in large part, to the nature of material culture: The artifacts of poorer people tend to not survive into the historical record.

Much of what Burdan was able to pull together comes from the closets and scrapbooks of wealthier families, with a notable exception: a large cloth banner reading “Working Women Need the Vote.”

“It’s very faded. It has spent a lot of time in the sun, I think,” said Burdan. The banner may no longer have its rich colors like those purple capes, nevertheless, it is important enough to be placed prominently at the entrance to the gallery.

“This banner, I hope, will have people start to think about who these women are, and who’s missing,” she said.

“Votes for Women: A Visual History” will be on view at the Brandywine from Feb. 1 to June 7.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.