They contorted their faces in a howl. With eyes bulging, mouths twisted, veins popping, the Titusville High School senior class, cheerleaders screeching out orders, filled the gymnasium with frenzied intensity as they bellowed out the name of their school mascot, letter by letter — rattling the grandstands and reaching for their maximum decibel.

“What’s that spell?” a girl screamed.

“Rockets!” the seniors answered. “Rockets! Rockets!”

Homecoming week had come to Titusville, Pennsylvania, and students across the small rural Northwestern Pennsylvania town were going bonkers, a mob scene of Rocket yellow and brown.

Seniors strutted the halls wearing war paint and letterman jackets. Multiple marching band parades were led through the streets. And injured middle linebacker Luciano DeRose gave a rousing speech of heartfelt violence before the Friday night football game.

“Make them think you are not human,” barked DeRose, a senior, in the pre-game huddle. “Because I promise you, if you keep hitting them, if you have that look in your eyes, they’re gonna break. And this is going to be a good night.”

As junior Samantha Pritchard, part of the drumline, put it:

“We need a reason to celebrate sometimes, so I guess this is it.”

For the past 25 years or so, finding reasons to celebrate have been harder to come by in Titusville.

Like many parts of western Pennsylvania, the town has been badly scarred by deindustrialization and steady population loss. It’s a far cry from the glory days of the 1800s, when it became the epicenter of the American oil boom after Edwin Drake drilled what’s thought to be the world’s first successful commercial oil well.

“Titusville is a historically world renown community,” said schools superintendent Karen Jez. “At one point we probably had more millionaires per capita than even New York City.”

Those days are long gone. Jez says the area sees significant brain drain, with far more home-leaving than home-coming.

“Our kids don’t see hope in our community as far as job opportunities,” said Jez.

Seventeen year old Heidi Drake, a junior, wants to be an eye surgeon.

“It’s nothing really against Titusville, but I think a lot of people want to get out of here just because they want to kind of expand their horizons and see different things,” she said.

Pritchard, who hopes to be a speech pathologist, agrees.

“People live here, and then they die here,” she said. “And I feel like there’s more out there.”

The headlines in coverage of Pennsylvania public schools tend to revolve around action in Harrisburg or issues in the state’s largest urban districts.

In much of the state, though, many small and rural districts like Titusville face challenges similar to their urban counterparts, just on a different scale.

There, too, educators stress over student poverty, school funding and how to better prepare students for a 21st century economy.

Titusville’s story is echoed across many towns in Pennsylvania, where a solid middle-class workforce was once sustained by no more than a high school degree. In Crawford and Venango counties, jobs left in waves in the latter 20th century after Pennzoil, U.S. Steel and Quaker State pulled out of nearby Oil City. The latter came as a devastating blow on the heels of the closure of steel mill in Titusville that had been a major employer.

As Jez drove around the district, she noted how the poverty rate has risen over time, and with it brought welfare dependency, drug addiction and sometimes students living in squalor. Median household income in the district is about $38,000, in the bottom tenth of the state.

“I went into a home one time a few years back as a principal, and half of the house still had dirt floors,” said Jez.

Titusville has benefited greatly from being the home of one of University of Pittsburgh’s satellite campuses, but the possibility of closure looms, with enrollment down 40 percent this decade.

The agricultural industry in the area has also been diminished, but it’s still not uncommon to find students like freshman Abigail Bryan. She spends nights and vacations doing chores on one of the family farms that dot the outlying lands of the district.

“I always think of myself as like the weird country girl,” she said. “I have to milk about 70 cows….and then we have about 25-30 calfs. So it’s a pretty decent-sized farm.”

Downtown Titusville is essentially one main drag with a motel on one end, a diner on the other and a strip of taverns and social clubs in the middle.

Inside one bar on a Tuesday night, there was a palpable restless energy. The bartender, who, when asked to describe the town, said, “it sucks,” was begged for a drink by a burly patron who’d been kicked out the previous weekend.

Another group of men came in after a work shift, fired up an Elton John song on the jukebox, and in a flash there was an argument over a girl, and a fist fight outside on the sidewalk.

“Bar fights are part of bars and part of alcohol,” said Titusville Police Chief Harold Minch. “These are tough blue-collar individuals that have lived here for generations. They’re woodsmen. They’re oil field workers. They’re steelworkers; these are not accountants. So, you know, you’re gonna say something about the Steelers, about their Penguins, and if they’ve had six beers, you’re gonna get punched in the mouth.”

Minch spoke alongside Jez and the head of the Titusville Redevelopment Authority. Yes, they said, Titusville clearly has its issues, but they downplay naysayers and are bullish about the town’s future prospects.

There’s a burgeoning industrial park filled with successful niche businesses; the ability to work remotely has lured some college grads back; and local leaders believe the area’s natural beauty makes it poised to take off as a tourist destination.

“Are we going to be the steel center of the world again? Absolutely not. Are we going to start pumping oil like they pump in Saudi Arabia? Absolutely not. It’s not going to happen,” said Minch. “However, that doesn’t mean there’s no opportunity here. That means there’s different opportunities here.”

In the middle of everything sits the Titusville school system, which for an area struggling to redefine itself, is a true community hub — for more than just students.

And nothing may get at this more than seeing the town come together during homecoming week to pack the grandstands for a Friday night football game.

“Everybody, like, really has your back if you ever need anything, and it’s just really homey feeling. You never feel like you’re out of place,” said DeRose.

‘Dirty Little Secret’

Football, though, can only do so much to move a town forward.

As seen in many parts of the country, the ongoing opioid crisis has ravaged Northwestern Pennsylvania, leaving a trail of grief and loss in its wake — undercutting attempts by towns like Titusville to revitalize economically.

Educators are also besieged by the issue, forced to grapple with how the actions of parents are harming children.

“You have parents come in, when you even talk to them, and you know that they’re on something,” said Diane Robbins, principal of Titusville’s Early Childhood Learning Center.

Principal Lisa Royek, of nearby Hydetown Elementary, sees it with the parents of young children too.

“I’ve had times I don’t let kids leave with parents because I know. And I’ve only had to ever pursue law enforcement for that once, but they’re usually pretty reasonable about it,” she said. “I’ll just say, ‘Hey, I don’t really think you ought to be driving with Johnny in the car.’ They’re usually like, ‘Yeah. Yeah, put him on the bus.’ I mean, they know.”

Parent Sarah Muir used to be an occupational therapist. What she saw on home visits in the area pushed her and her husband to become foster and then adoptive parents. They now have full custody of six children — three blood relation, three adopted.

“I see that end of it, kids being neglected,” she said. “You can see it as a culture that kids are suffering.”

It’s what Minch calls the “dirty little secret” of the current drug crisis: the collateral damage being caused on children.

“Those children must be taken care of by somebody, and many times it falls to the grandparents,” he said.

In 2016, the top four counties in Pennsylvania for drug overdose rates were rural ones in the Western part of the state: Fulton, Cambria, Beaver and Armstrong. Crawford and neighboring Erie county both had rates in the top third. Here, similar to the statewide dynamic, most deaths occur in adults aged 25-44.

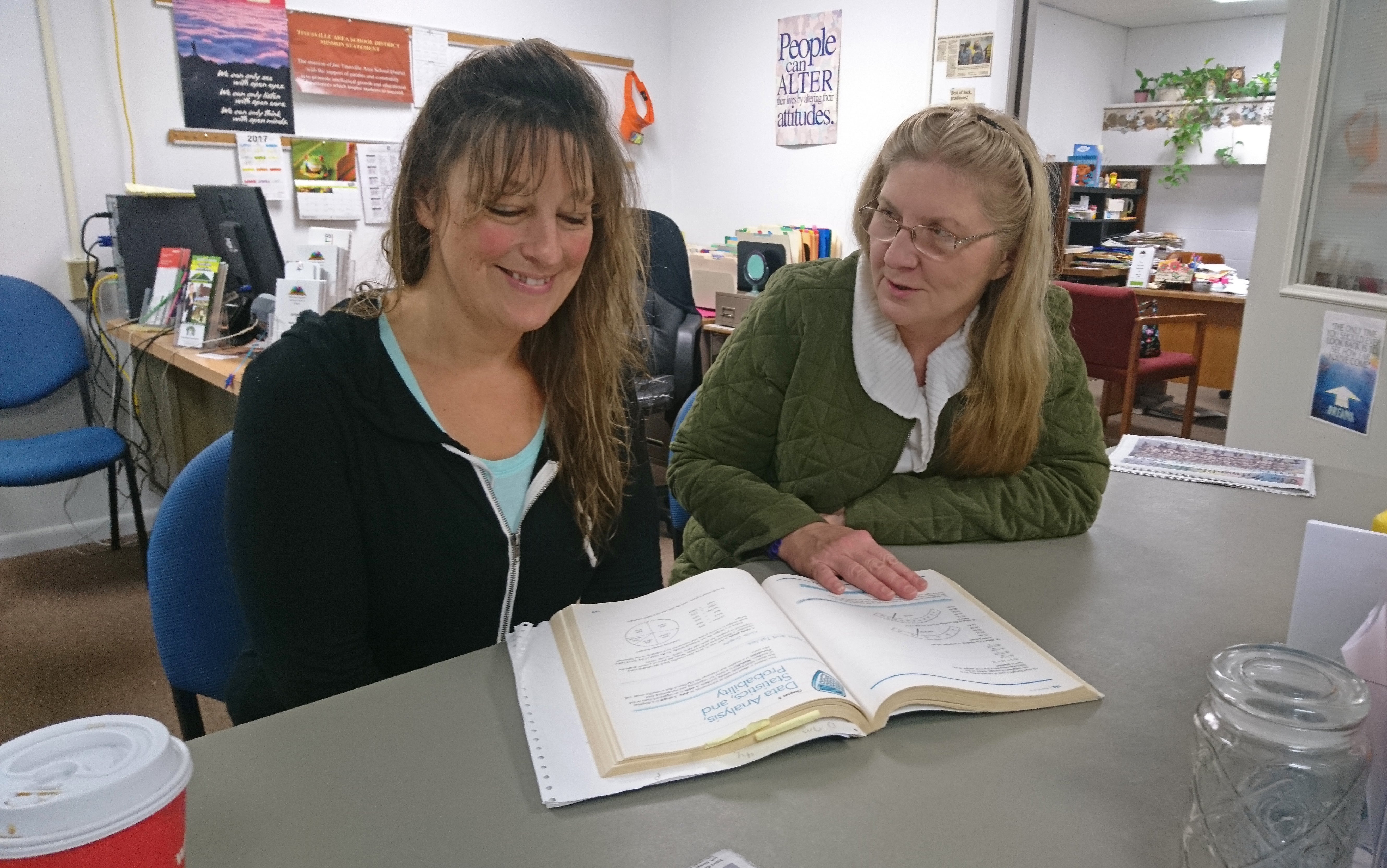

“In a little over a year. I lost five former students to drug overdoses. The opioid epidemic has definitely hit here, and it’s huge,” said Kelli Davis, executive director of the Titusville Regional Literacy Council, a community resource that helps high school dropouts find a path back to a diploma.

In Crawford County, estimates say 1 in 5 adults can’t read well enough to function in society.

“We’re a second or third or fourth or 10th chance for somebody,” she said.

One recent overdose sticks out vividly in Davis’ mind.

“An employee of mine came in and said, ‘Did you hear about’ — we’ll call him John — ‘Did you hear about John?’ And I said, ‘No.’ She said, ‘He overdosed last night.’ I said, ‘Oh no.’ I’ve been working with him for years and I knew he had addiction issues. I said, ‘How bad was it?’ And she said, ‘Oh Kelli,’ she said, ‘He didn’t make it,’ and it just … my heart fell to the floor. I mean, it takes a piece of me every time.”

The signs of Titusville’s distress make themselves far less visible compared to, for instance, Philadelphia, where open-air drug markets are prevalent in certain pockets of the city. Titusville is a quaint, proud town surrounded by a gush of natural beauty. And you can walk around at night with little to worry about.

But, if you’re looking, the evidence of despair is not hard to find.

During a ride-along one morning with Chief Minch, he came upon middle-aged woman trying to traverse a steep rural road in a motorized wheelchair. A distant stare in her eyes, she refused to stop when Minch pulled his cruiser alongside. Minch then cut her off, and spoke to her in the middle of the road before letting her proceed.

“It’s a hard situation. She’s in her right mind” he said. “She has a cell phone. She has a destination. She says she does it quite frequently.”

He said she’d ended up in the wheelchair because of a car accident, and subsequently ran into trouble with the county based on overdue court fines. He said her son’s truancy has also caused the family legal problems. The woman claimed to be heading into town to find her husband, who Minch believed was hiding out in a tavern.

“Her world is coming apart,” he said.

Later in the day we came upon a house in an otherwise well-kept neighborhood that was squatted in by addicts.

“It’s not uncommon to find needles up here — not only heroin, but they melt the pills down and shoot them as well,” said Minch as we approached the house. “That’s standard all over the country now.”

Inside was a nightmare — an overwhelming scene of filthy neglect that town workers had spent the morning trying to clear.

“Sad thing is there was a baby in here with them,” said one worker.

“I know…” said Minch. “That momma’s on probation too. I watched her pee dirty right there in the probation officer’s office two weeks ago.”

One of the workers showed Minch all the needles they found.

“Good lord,” he said, surprised.

“Bags and bags of needles. And you know there’s one there, one there,” the worker said, pointing around the room.

Upstairs, there was a crude marijuana grow operation, and in the back bedroom, parts of the roof were exposed with the ceiling molded over.

“Oh, this is pretty bad right here,” said Minch. “This is fairly spectacular … This might be one of the worst I’ve ever seen. I mean that’ll kill ya.”

The struggle against drugs is nothing new to Titusville. In the early 2000s, the rural Northwestern part of the state, and Titusville specifically, garnered the nickname “the meth capital of Pennsylvania.”

A subsequent crackdown helped dispel that distinction.

Minch, who’s new to town from much larger Naples, Florida — where as a captain he oversaw the vice and narcotics unit — says it was probably never deserved to begin with.

“It kind of made me giggle when I heard this ‘meth capital of Pennsylvania.’ You’ve got a pretty weak meth operation here in Pennsylvania if this is the capital,” he said. “You guys flat suck at this.”

Since Minch arrived, he says he’s gotten the few homeless drug addicts that existed off the streets and has pursued the small time dealers and producers in the region aggressively. Minch lives in the center of town, right across the street from the high school, and he’s already arrested a few of his neighbors.

“I’m a stalker. That’s what I do. I’m a predator; so I’m coming after you,” he said. “And I tell them that freely. I tell them on TV quite a bit. When I see them in person I tell them. They know I’m coming. It’s not a surprise when we come and get them.”

But drugs clearly remain a problem. And he’s less sure about what to do with the users.

“They may not be able to pass the drug test at the place they’re going to get hired, and they would rather sit home, smoke dope, and badmouth their country and take the check,” he said. “And we have a lot of that. A lot of the places in this part of the country have that. And once you get on that road — you haven’t worked in three or four years or two years or whatever it is — how are you going back?”

Families such as the Muirs are doing their part to give the community a boost. They opened a coffee shop this year that they hope can become a beacon.

“There’s really nowhere for people just to hang out in Titusville,” said Sarah Muir. “I mean you have Sheetz and McDonald’s, but nowhere really just to…that was my main drive was just to have, you know, more of the gathering place for a positive influence in town.”

It’s the school system, though, that has the greatest opportunity to affect change. It’s not that students themselves seem to be using or dealing hard drugs, but with many of them growing up in this culture, it’s easy to wonder what will happen next — especially for those who stick around and find it tough to secure a middle class job.

“It’s an escape. And sadly, it’s affordable and it’s here,” said Royek, principal of Hydetown elementary.

Recasting the notion of school

The school system has worked to provide the right supports for students and families. Titusville was on the forefront in the push for universal pre-K, starting its program in the early 1980s. It’s also invested recently in training teachers to help students deal with trauma, and provides easy access to Davis’ adult literacy programs.

Those back-end programs have been lifelines for people like Becky Southwick. When she dropped out of Titusville High School 25 years ago, she was pregnant, overwhelmed by things going on in her personal life, and disconnected from anything happening in her classes.

“I had like three or four months left and I just had a lot of things going on,” she said.

Now 43, she’s been diligently working with the Titusville Regional Literacy Council on her G.E.D. — hoping to set an example for her four kids by one day becoming a registered nurse.

“Letting them know that: don’t ever quit because you can do anything with your life,” she said. “Not letting them see their mother be a failure or just stopping and just because life gets difficult or hard.”

It was, in part, people like Southwick who district leaders had in mind when thinking about how to redesign Titusville’s elementary education offerings — seeking a system that would better meet students where they are, keep them more engaged, and make them more creative and collaborative thinkers.

To this end, Titusville piloted a “mass customized learning” model in Hydetown Elementary during the 2016-17 year, recasting traditional notions of school.

“The Industrial Age model isn’t going to work anymore, because those factory jobs aren’t there,” said Royek. “When we put them into an industrialized model and they get frustrated every year of school more and more, that’s when they drop out, and then they’re stuck in this, you know, they don’t have any 21st century skills to escape.”

When Royek says “industrialized model,” she means what people typically think of as normal school: students sitting in straight rows, following directions from a teacher at the front of the room, and learning the same material in large cohorts arbitrarily grouped by age.

She believes that theory is outdated — an especially bitter pill for regions that have seen up-close the rise and fall of industry.

“All the research behind this says that employers now aren’t looking for people who can push the same button,” she said. “They need problem solvers and collaborators and kids who can think outside the box. And to make it, to get a job around here, you really have to be able to do that.”

So what exactly does this new type of school look like?

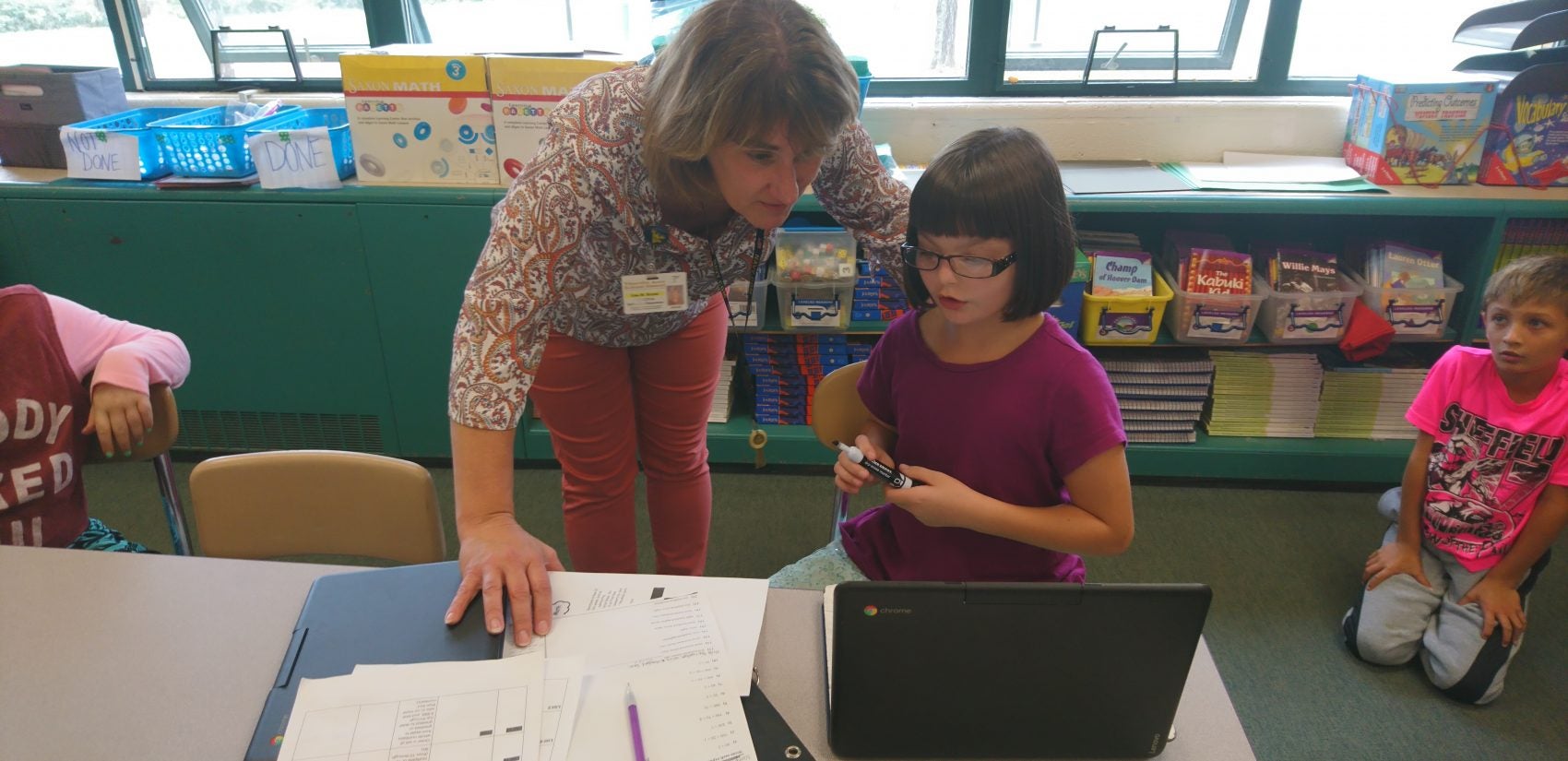

The school doesn’t organize students by grades, instead grouping kids by where they fall on skill continuums. This blends together students of different ages, and, in theory, keeps them constantly challenged, but never overwhelmed.

You can feel a palpable difference just by walking into the school. What counts as a classroom is a fluid idea, with classes regularly taking place in places like the cafeteria.

“We use every space in this building,” said Royek on a recent tour. “Absolutely.”

Students, called “learners,” work at their own pace and can only move on after proving mastery of a skill. And teachers, called “learning facilitators,” are less siloed and pushed to think beyond covering content.

“It used to be you could teach the chapter in the book and say, ‘Well I taught it. They didn’t get it. I have to keep moving.’ So now they have to say, ‘I have to figure out how to get them to get it,’ like, this isn’t a choice anymore,” she said.

Royek says it’s the typical ‘A’ students who’ve struggled most with the change.

“Because they were never finished, and it frustrated them,” she said. “Used to be I got my ‘A’ and I could do whatever I wanted to, and now I gain proficiency and you give me something else.”

Students like Brianna Nichols, though, say they love the added flexibility and the use of technology. All students have chromebooks.

“It’s actually helping me learn more. I like that we can work our own pace,” she said.

Hydetown’s model is part of a recent trend in education that puts a high priority on personalized learning — spurred in part by thinkers like Ken Robinson, whose 2006 TED Talk was viewed almost 50 million times:

“If you think of it, the whole system of public education around the world is a protracted process of university entrance. And the consequence is that many highly talented, brilliant, creative people think they’re not, because the thing they were good at in school wasn’t valued or was actually stigmatized. And I don’t think we can go on that way,” said Robinson in the talk.

Several other districts in Pennsylvania have implemented MCL to some degree, but what’s happening at Hydetown is considered to be on the vanguard among elementary schools.

Tom Butler, a director of the Mass Customized Learning Mid-Atlantic Consortium and executive director of Appalachia Intermediate Unit 8, praised the school for prioritizing student competency.

“It’s just radically learner-centered. That’s what that place is all about. It’s not about adult convenience. It’s not about the adults in the system. It’s all about the kids and the learners,” said Butler.

Skeptics fear the idea is being implemented too quickly without a solid basis in research to prove its effectiveness. What if the lack of traditional school structure actually does a disservice to students?

At Hydetown, the first year of the pilot program brought standardized test results that are not flattering.

Fewer students were deemed advanced or proficient in math and science. And more students fell to the lowest “below basic” level in math and English. Proponents say standardized tests are an imperfect gauge for an educational model that prioritizes creativity and collaboration.

Superintendent Jez says she’s willing to give Hydetown a few more years before reading too much into state test scores.

“One year of it is really no way to judge it based on PSSA scores,” she said. “That was one year of implementation.”

Principal Royek herself was initially wary of implementing the model until teachers convinced her it could be a gamechanger. Now she’s all-in, believing it will put students ahead of the curve for the digital-interfacing jobs of tomorrow — ones she hopes may just help revitalize a region struggling to find its economic footing.

“These kids could grow up and have a job, a really good paying job and stay here in Titusville, but they have to have the skills to do that via a distance,” she said. “It’s no longer, ‘Go to the factory.’ Now you have to take your skills via technology out there.”

The harmed and the harmless

No discussion of Pennsylvania’s rural school districts would be complete without delving into the effects of two of the most contentious words in the commonwealth’s school funding debates.

“Hold.” And “harmless.”

As a policy, this refers to the practice adopted by the state in the early 1990s that protected districts like Titusville from being hurt financially as school enrollment dwindled.

Under this policy, no matter how many students a district lost year to year, state funding was never scaled back. Money flowed without regard for actual student enrollment, and these districts were “held harmless.”

It’s why if you look at state funding, many rural districts in the Western half of the state get the most money per pupil.

Of 500 school districts, Titusville — where enrollment is down nearly 30 percent since hold harmless was implemented — is ranked 59th in terms of per pupil funding as distributed from the state’s largest pot of education cash. This nets them about $6,900 per student, not counting other state, federal and local revenue streams.

Below Titusville on this list are several districts with higher poverty rates, including Shenandoah Valley SD, Sto-Rox SD, Philadelphia City SD, Lancaster City SD, Shamokin Area SD, Panther Valley and nearby Erie City — which teetered on the verge of a financial collapse recently, threatening to close all city high schools.

And there are districts wealthier than Titusville that receive more per pupil aid from the state.

The seeming inequity in this dynamic is a large part of what fueled the state’s adoption, in 2016, of a new widely-praised, bipartisanly-backed school funding formula. It’s based on real student factors such as poverty, english-learner status, and, crucially, actual enrollment.

Hold harmless, though, still largely rules the day, as leaders have decided to use the new formula only to distribute new allocations of state school funding — which currently account for about 7 percent of the whole basic education subsidy.

This has been frustrating for the many districts in the state that feel their needs haven’t been accurately reflected in state budgets.

To some advocates, the solution is simple: flip the switch and run all state funding through the new student-weighted formula. Even if this would hurt some districts, they say it’s the quickest way to rectify what they see as an ongoing injustice.

But, to a district like Titusville, this would be devastating.

“Some schools, I’m sure in Southeastern, say, ‘Well just hit the reset button and go right to the new formula,’” said Titusville business manager Shawn Sampson. “Essentially that would pretty much put most of the schools in this area out of business with a year or two.”

In that scenario, Titusville would get about $3 million less from the state in basic education funding, a loss of about $1,500 per student.

Neighboring Corry Area School District — spread across 250 square miles in Erie, Warren and Crawford counties — would fare worse. There, Superintendent William Nichols has been ringing the alarm about the damage that could be done to many rural districts even by staying on the current course.

“Fair, equitable funding, to us, is gone,” said Nichols. “It’s over.”

In Corry, years of hold harmless funding have helped the district build and maintain some very robust programs, including a top-notch vocational hub.

In one hallway, there’s a mill shop, an automotive garage, and a hydroponic-gardening classroom — that’s on top of offerings in nursing, daycare, multimedia production, welding, construction and others.

For senior Brian McGinnett, who has struggled with some traditional academic subjects, having daily access to these programs has helped him find direction in life.

“Mom said I can’t do something and I proved her wrong. I made something of myself and I did it,” said McGinnett, whose specialty is construction. “And, pretty much, I have a guaranteed job after school.”

Corry’s programming could be a point of envy for other districts in the state, many of whom pool resources to run shared vo-tech facilities, busing students to a centralized location.

Nichols says his arrangement better serves Corry’s largely poor student body, many of whom already spend hours a day being bused across the sprawling district’s many dirt roads.

But it’s costly, and he fears the new state funding scheme could one day force the district to scale it back.

“Our kids are very fortunate to have the program they have now. So I defend that program,” he said. “The problem I see is … we’re not going to be able to keep those programs.”

Chemistry teacher Roxann Dougherty says classrooms already have been feeling the pinch. “Now, rather than doing the experiments that we used to do. We are down to a few experiments — not very many because we don’t have the money to buy the supplies that are necessary,” she said.

Reading the writing on the wall, Corry officials say they’ve taken many steps over the past few years to become more efficient and fiscally prudent. They shuttered three elementary schools, reduced their consumables budget by half, and reduced 50 employees through attrition — increasing class size to compensate.

The board authorized the cuts in an attempt to keep local property taxes in check, hoping to make the area more attractive to prospective homebuyers.

But with a less generous allotment of state funding coming in, Corry fully anticipates that the burden on local taxpayers will continue to grow — especially as costs for transportation, employee pensions and special-education services remain large.

But demanding more from taxpayers has become an increasingly tough ask in a community that’s seen factories shuttered and opportunities diminished.

“A lot of the well-paying jobs have moved out. So the poverty level has grown. It makes everything a little more difficult,” said Corry High School principal Kelly Cragg, a lifelong resident. He’s specifically concerned about the effect on the town’s senior citizens.

“The older people’s tax keeps going up, and their money doesn’t keep going up. They just keep squeezing the belt tighter, and it’s not fair,” he said. “I don’t know what the answer is.”

To Nichols, the new school funding formula counts as one more in a string of state policy decisions with which he disagrees.

The state’s charter school law undercuts the district’s ability to control costs, he says. For instance, when Corry closed an elementary school in an outlying part of the district in an attempt to rightsize, a charter applied to take its place. The district then had to spend precious resources in its ultimately successful attempt to deny the application.

The state’s cyber charter law is particularly hateful in his eyes, bad for the students he sees cycle through the schools, as well as the district’s budget.

“Nothing’s happening to them except we’re making a payment for them to the charter school,” he said. “And then we have to remediate them when they come back, or we have to face high discipline problems.”

And while he says he’s sympathetic to districts like Erie City that have long been on the short side of the state’s funding logic, he rejects the idea that the new formula is “fair.”

He cited, for instance, the fact that a significantly wealthier district in Erie County received a larger increase in state funds this year compared to Corry’s allotment. This occurred largely because the state is now counting actual student enrollment, but it smacks of injustice to a district like Corry — home to a large federal low-income housing program and weighted by a legacy of distress, where some families lack access to even basic utilities.

“We still have — not many families anymore — families without running water, inside toilets,” he said.

Driving around the district with Nichols, we came upon a trailer park where bedsheets were used as curtains — another neighborhood in the center of town filled with dilapidated apartments.

“So we have a significant number of families where grandpa was on welfare, dad’s on welfare, and now the children are headed for welfare,” he said. “That’s really what some kids even call it. ‘That’s my dad’s career. We’re on welfare.’ And they will tell you that.”

At the same time Corry is stressing over its economic future, just as in Titusville, educators say student need is increasing.

“Now you have kids who go home one night, there’s different people in their house. They don’t know who’s coming or going. They move in with ‘so-and-so’ because they’re out of money. They have, I don’t know, 10, 12 people living in the house,” said Susan Barra, Corry’s vo-tech supervisor and former guidance counselor. “Maybe you had a kid that was a little bit depressed 20 years ago. Now we have kids who are actively suicidal who need mental health treatment all the time.”

This all gets at a central tension in Pennsylvania school funding.

The districts that are the biggest winners in the new state formula are some of the largest urban ones with even greater concentrations of poverty than Corry or Titusville — many of whom could look to the rural Northwest wishing they could provide what these districts have historically been able to offer.

In order to appease both the poor urban districts and the poor, mostly rural “hold harmless” districts, advocates say the state should dramatically increase the state education budget each year, with calls for up to $400 million boosts annually. This, they say, would create a more equitable and adequate system overall.

But that sort of financial commitment would require a sizable chunk of new revenue from state taxpayers, which many in the legislature say would be untenable. For context, through three contentious budget cycles under Governor Tom Wolf, the state has upped the basic education subsidy by a total of about $470 million.

Without a dramatic change, year by year, it’s likely that districts like Corry and Titusville will trim, tighten and/or tax locally in order to adjust to their new normal.

“Any cuts we make from this point on are going to penalize kids, penalize kids’ families,” said Nichols.

On the Titusville football field, concerns about long-term school district budgeting could scant be found on homecoming night. The players had their hands full with more pressing matters. Under a dusky autumn sky they grunted and scraped against rival Cochranton, but fell well short of their hopes, losing in a rout before going completely winless on the season.

Superintendent Jez, though — committed to the idea of renewal — couldn’t help but find a silver lining.

“Our kids are young and little,” she said. “I think our average weight is about 170 pounds this year. So, you know, our line is not very big, but they have heart.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.