In Erie, a microcosm of Pennsylvania’s struggle for education equity

Listen

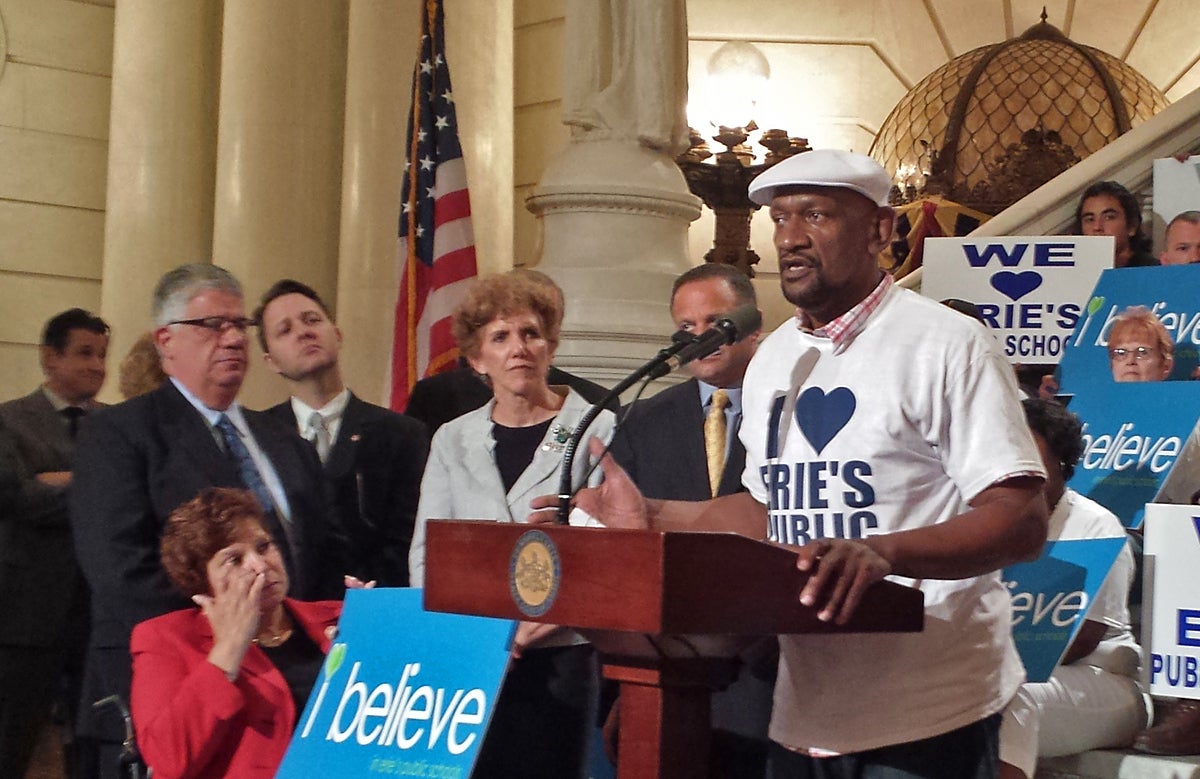

Superintendent Jay Badams leads a coalition of students, parents, educators, and community members at the state capitol in Harrisburg, Pa., urging state lawmakers to alter policies that have left Erie's public schools on the brink of insolvency. (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)

State policy has pushed Erie Public Schools to the brink of insolvency.

Urban school districts in Pennsylvania face a particularly cruel logic.

They serve the poorest, most needy students, yet, when it comes to state funding per pupil, most of them don’t make the top of the list.

That dynamic has come to a head in the city of Erie, where leaders of one of the largest school systems in the state are contemplating closing all high schools.

In early June, busloads of people from the Gem City made the nearly five hour trek to Harrisburg to deliver a simple message to any lawmaker who would listen.

Parents, students, educators and community members stood on the steps of the grand capitol rotunda chanting:

“Fund our schools! Please! Fund our schools! Please!”

Leading the group was Jay Badams, who — in the face of Pennsylvania’s systemic school funding inequities — has become the most vocal, moral crusading superintendent in the state.

“We can’t take any more away from our children,” he said. “So I’m asking all of you, just please, please remember Erie.”

In May, Badams made headlines for drawing line in the sand. After six years of austerity under his tenure, he urged Erie’s school board to adopt an out-of-balance budget to avoid more cuts that would eliminate sports, arts, music, extracurriculars and guidance counselors.

At the same time, he asked the board to study the possibility of closing all of Erie’s high schools after the upcoming school year and sending students to the outlying, better-resourced suburban districts.

In an interview in his office in downtown Erie after the Harrisburg rally, Badams acknowledged that the school closure plan has to do with much more than short-term fiscal constraints.

“This becomes a matter of fairness,” he said. “And if our students would need to attend schools in other districts in order to have some sort of equity, then that may end up being the most ethical and moral decision.”

How did Erie end up in this position?

Like many conversations about school funding in Pennsylvania, the answer takes you back to Harrisburg — out of which there hasn’t been a student-weighted funding formula for most of the past twenty five years.

So even though Erie is one of the most impoverished districts in the state, and has one of the highest percentages of English language learners, the district currently receives less per-pupil funding from the state’s main pot of cash than about 200 other districts.

The disparity in Erie County alone is shocking. The city district is by far the poorest and most challenged, but eight of the other 12 districts in the county get more per-pupil state funding.

That’s a fact that Badams can’t fathom.

“There’s a perception out there that kids living in poverty, kids living in the inner-city, don’t know what they’re missing,” he said. “Well, they do know what they’re missing.”

The signs of Erie’s fiscal distress would be hard for students to overlook.

Many of the aging school buildings have crumbling infrastructure. Books and technology have lagged behind the times.

And staffing levels have been cut at the same time the city’s violent crime rate has grown.

“It’s depressing how kids our age will go around and shoot other kids in our age group. And we have to deal with losing friends, family members at such a young age,” said Whitney Henderson, a sophomore at Strong Vincent High School.

Henderson says that gangs are threatening peace in the city.

“The kids that go around with the guns shooting, they just think they’re cool. They want to be a part of a gang, want to be a part of something,” she said.

Whitney Henderson, a sophomore at Strong Vincent High School (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)

This is part of what drove Badams to push back against the idea of cutting sports, extracurriculars and counselors — a decision which Arlan Pulliam, another Strong Vincent sophomore, cheered.

“Football and all these other academics are keeping most kids out of trouble, and without those programs, kids will be way, way worse,” he said.

A few blocks away, Roosevelt Middle School principal Teresa Szumigala says, even without more cuts, the situation is already untenable.

“We do see students that we don’t necessarily have the correct interventions for because of the lack of funding,” she said. “To be able to provide those kids with the right path is what our ultimate goal is.”

Stopping bullets

On the night before Erie’s busloads of advocates headed to Harrisburg, an 18 year old former Strong Vincent High School student was murdered in a drive-by shooting.

Daryl Craig, a former gang member and now leader of a local anti-violence group, stood on the rotunda steps urging lawmakers to see how state education policy was making these matters worse in Erie.

“They have a saying in the circles of nonviolence now, that, ‘Nothing stops a bullet like a job.’ And I agree with that. But nothing ensures a job like an education.”

Daryl Craig (right) speaks to state lawmakers at the state capitol in Harrisburg, Pa, urging them to provide relief for Erie’s public schools. (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)

Sitting in the crowd before the Erie advocates was State Senator Scott Wagner, R-York, an anti-tax Republican whose independent wealth has made him a powerful player in the capitol.

He’s currently backing a bid to unseat incumbent State Sen. Sean Wiley, D-Erie.

If advocates hoped to garner support for additional state funding on their trip, Wagner would be one of the toughest sells.

“We don’t have a revenue problem,” he said in an interview after the rally. “We have a spending problem.”

Wagner, who’s considering running for governor, proposed closing Erie’s budget gap by cutting more teachers and reducing educator salaries — which are already below state and county averages.

“Nobody wants to fix the problems, it’s just, ‘let’s throw more money at the problem,'” he said. “And every time you do that, the money disappears and the problem is still there.”

Superintendent Badams readily acknowledges that his predecessors could have done a better job of managing the district’s finances. In the lead up to the recession and the first few years in, many staff positions were added with no long term plan to fund them.

The central office became bloated, and grant-funded programs were not initially curtailed when funds ran dry.

But the cuts to rectify the past have now been made.

The district closed three school buildings, eliminated 200 full-time positions, cut the central office in half, and held employee wages largely stagnant.

Excluding pension costs, per-pupil spending in Erie is less than it was in 2008-09.

Considering these moves in the context of rising fixed costs for pensions and charter schools, Badams says the solution to Erie’s woes can only come from the state – especially when factoring in the city’s already high property tax rate.

“It’s just increasingly difficult for us to close our margin by turning to our local taxpayers,” said Badams. “We’re already driving people out of the city as it is.”

Short-term relief, long-term struggle

Erie’s advocacy worked, at least in the short term.

The district got relief in the state budget that recently passed, including a $3.4 million boost in basic education funds, and a one-time $4 million dollar emergency supplement.

In concert, this aid allows Erie to avoid slashing programs in the coming year.

But the systemic issues will persist, and Erie’s finances are slated to be in the same sorry straits by the end of the school year.

But consider this:

If lawmakers had chosen to distribute the entire basic education subsidy using the new student-weighted formula, Erie this year would have received an extra $39.7 million.

That number dwarfs this year’s deficit. It would allow Erie to reopen vital programs, reduce real estate taxes down to county average, and help remedy its crumbling infrastructure.

But, if that had happened, 70 percent of the districts in Pennsylvania would lose out, including nearly every other school district in Erie County.

Instead, lawmakers plan to use the formula only to distribute new money as it is added to the pot, which at this point is about six percent of the whole.

The graph below shows how Erie Public Schools would fare if lawmakers decided to implement the new formula more aggressively.

If lawmakers proceed as planned, the inequities that have grown over the past few decades will likely make up the lion’s share of the pie for many years to come — leaving Badams to continue ringing the moral alarm.

“I think it’s patently unfair,” he said. “It’ll take generations of students to go through our unfairly funded schools before we’ll see that fairness.”

This is part one of a two-part series on Erie Public Schools. In part two, Keystone Crossroads will more closely examine the plan to close Erie’s high schools, a proposal that would amount to a massive race and class integration effort.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.