Report finds students of color shortchanged by Pa. school funding

Critics call the analysis "spin."

Listen 5:45

Students change classes at Julia de Burgos Elementary School in Philadelphia, Pa. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

With its new student-weighted school funding formula, Pennsylvania took a big step forward this year to begin to correct decades of inequities.

But much of the disparity that has grown over time is set to be locked in place for many years to come.

A new study by the faith-based advocacy group POWER looks at this dynamic, and finds that school districts serving more students of color will be most negatively affected.

POWER says this amounts to “systemic racial bias.”

The new formula itself has been widely lauded, as it injects common sense into what had become a haphazard and unscientific system for distributing state aid.

If the new formula was used to divide the entire basic education subsidy — which is by far the largest pot of state school funding — the most money per pupil would go to the schools facing the greatest challenges.

This would be a major boon for districts with more students of color.

But that’s not the plan.

Lawmakers aim to use the formula only to divide new increases in funding. So, at this point, of a $5.8 billion pot, that adds up to about six percent of the whole.

“What we’ve said is, now that we understand exactly how racially biased the historical funding has been, let’s lock it into place and continue it going forward, and only change it in a very minor way, diluting it with a little bit of fair funding,” said David Mosenkis, the report’s author.

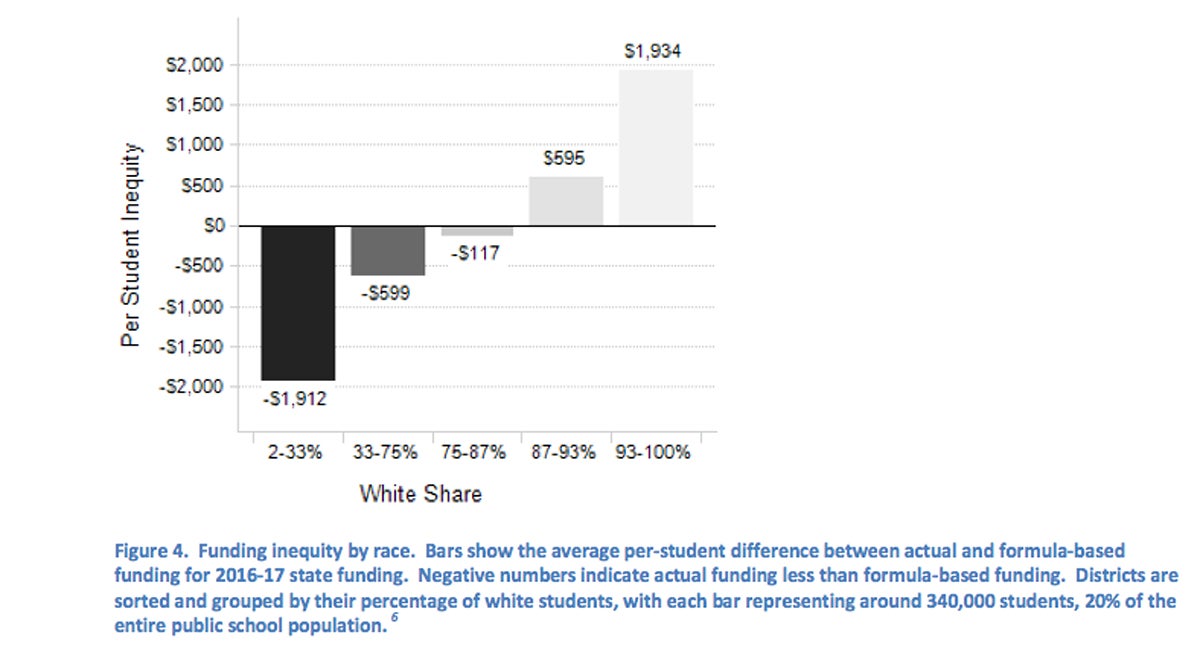

As is, Mosenkis finds that the districts with the fewest white students are currently shortchanged according to the formula by almost $2,000 per pupil, while the districts with the most white students get about $2,000 more per pupil than what the formula says is their “fair share.”

(Chart courtesy of David Mosenkis of POWER)

Even when controlling for poverty, POWER’s report finds that “race is a robust indicator of funding inequity.”

A Keystone Crossroads analysis finds that this occurred largely based on a “hold harmless” state policy that has historically favored districts with declining student populations.

Mosenkis agrees that current inequities aren’t the product of overt racism.

“There are a lot of ways that racism manifests itself in our society,” he said. “And a lot of them are not because individuals are consciously racist, or making decisions to consciously underserve or discriminate against people of color.”

This report follows up a similar analysis performed in 2014 by Mosenkis, a data scientist by trade.

His work was verified and duplicated by Research For Action, a nonprofit organization focused on education research.

Path forward?

Correcting these inequities by fully implementing the formula has been a political non-starter, as that would essentially benefit 30 percent of the school districts in the state by taking funds away from the rest.

So POWER is pushing for a middle ground, urging the state to set a more aggressive timeline to fix the problem.

For instance, lawmakers could decide to fully implement the formula within 10 or 15 years. This would give districts where enrollment has declined time to adjust, while putting the neediest districts on a faster track to relief.

House Republicans, though, say the group is hurting its argument by framing it around race.

Spokesman Steve Miskin says the report is “spin to garner attention.”

“If you want to have a conversation about distressed districts and distressed schools, we’re open to that,” said Miskin. “But to slap a racial label doesn’t do anybody any good. It just charges a situation that doesn’t need it.”

Keystone Crossroads reached out to diverse sources for feedback on Mosenkis’ report.

A spokeswoman for Senate Republicans said they have “no opinion” about its merits. House Democrats didn’t reply to a request for comment.

Governor Wolf’s administration declined to weigh in, but said it would continue advocating for additional state spending on schools.

State Senator Vincent Hughes, D, Philadelphia — the highest ranking African-American lawmaker in the capitol — said leaders need to take POWER’s findings seriously.

“They can deny the race reality of this, but the race reality is in fact a reality,” he said. “For folks to ignore that, they’re just putting their head in the sand. They live in a different kind of reality than what exists for these kids who deserve their attention and who deserve their support.”

The Philadelphia School District, home to the largest number of students of color in the state, declined to comment on POWER’s report.

But School Reform Commissioner Bill Green, appointed by former Governor Tom Corbett, offered insight to the district’s thinking.

“I agree with the premise [of the report], and the District has done its own analysis which we have shared with appropriate authorities through one of our attorneys,” said Green. “We look forward to full implementation of the fair funding formula. Until it is fully funded, by definition, many Pennsylvanians are not receiving a thorough and efficient public education.”

The Commonwealth Foundation, a fiscally conservative Harrisburg think tank, also agrees with POWER’s premise, but says political realities can’t be ignored.

Legislative leadership on both sides of the aisle represent districts that would lose funding under the plan forwarded by POWER.

“Ultimately, the bottom line is, everyone would be better off if the funding was student-based, and that means making better use of the new formula,” said James Paul, senior policy analyst at Commonwealth. “But I also recognize that there are a lot of lawmakers who represent declining population districts, and it’s going to be a heavy lift to make.”

Miskin, too, emphasized the long, winding road it took to reach common ground on the formula itself.

“The magic math is 102 [votes] in the House, 26 [votes] in the senate, and a governor who agrees,” he said. “And if you don’t have those numbers, it doesn’t matter what statistic is there.”

Even Hughes, who applauded the report, said he would not push for a more aggressive formula implementation. Like many other advocates, he says the best path forward is to press for more new funding.

“I understand [POWER’s] perspective,” he said. “I’ve got to build on the victory that we just had.”

If the state boosts basic ed funding by $200 million every year, it would take more than 25 years for even half of state funds to be distributed according to the formula.

Sharif El-Mekki, the principal of the predominantly black Mastery Charter at Shoemaker High School in Philadelphia, says political difficulty should not be the excuse that allows that to happen.

“There’s a lot of mouthpieces that talk about their commitment to marginalized communities, their commitment to underserved populations, but time and time again, when it’s time to do something about it, people shrink and they become impotent, and they don’t do what’s best for kids,” said El-Mekki.

It’s important to note that districts most concentrated with students of color have often received special funding allocations from Harrisburg that are not included in studies of the state’s main pot of education cash.

For instance, this year, Erie received an extra $4 million. In 2013, the state directed $45 million to Philadelphia to help it restore some guidance counselors.

These, though, were one-time infusions that are dwarfed by the amount the formula says these districts should be receiving on an annual basis.

That’s why Erie superintendent Jay Badams agrees with the report, and continues to beat the drum for change.

“If people who are actually making policy don’t want to listen to it, I guess that’s certainly their prerogative,” said Badams, who sits on the state Board of Education. “But I think people in the public, they’ll take note. And then it’s up to them — and those of us who are aware of this, and realize that it needs to be corrected — to do something about it.”

State lawmakers are scheduled to return to session in mid-September.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.