‘Renaissance in the Belly of a Killer Whale’ takes on gentrification, collective memory at the Wilma Theater

Three friends chronicle the gentrification of their changing hometown and call for a new Harlem Renaissance in the Wilma Theater’s newest production.

Listen 1:27

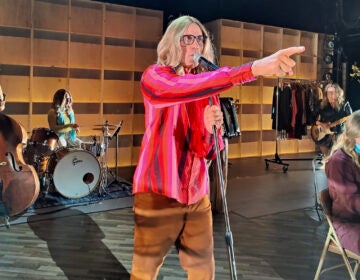

"Renaissance in the Belly of A Killer Whale" at Wilma Theater, with (from left) Janelle Heatley, Hollis Heath, and Jaylene Clark Owens. (Courtesy of Johanna Austin)

How is Harlem like the belly of a killer whale?

“It’s almost as if the belly was originally all black, and then you just had this strip of white come up in the middle that kind of pushed the black to the side,” playwright and director Jaylene Clark Owens said. “That made me think of gentrification in Harlem because it’s like you have the white residents coming in and Black residents being pushed to the side.”

“Renaissance in the Belly of a Killer Whale” is the play Owens — a Harlem native and longtime spoken word poet — co-wrote with Hollis Heath, Janelle Heatley, and Chyann Sapp to voice their feelings about the ways the neighborhood is changing.

The play, which is currently at the Wilma Theater, centers around three childhood friends — Bridget, Toni, and Shayla — who watch their beloved Harlem shape-shift under the pressures of gentrification. As rising rent and property taxes hit the neighborhood, Bridget’s family can no longer afford their brownstone. Part play, part poem, part song, part dance, the production illustrates how powerful culture can be as a tool of resistance in the face of erasure.

As the women gather on Bridget’s brownstone stoop and swap memories of girlhoods spent jumping double dutch and eating popsicles from the corner bodega, the past floods into the present, and sheds light on the women’s anxieties about Harlem’s future and deep nostalgia for their authentic home.

The actors reclaim popular dances like Harlem’s own “Chicken Noodle Soup,” made viral by hip-hop artist DJ Webstar, and the “Harlem Shake” by embodying those art forms back in their place of origin. Here, gesture becomes a kind of collective muscle memory meant to recall a Harlem of the past, particularly as these local cultural forms like dance, food and music continue to be commodified and consumed en masse by people outside of the neighborhood.

Owens said the creation of the play came from a desire to chronicle the many faces of gentrification, and the many people who interact with or are touched by a changing neighborhood.

“I remember Janelle [Heatley] and I walking home one day and us looking at the buildings… and we were like, ‘Look at this, you really have the projects right across from this new condo,’” Owens said. “Imagine what these buildings are saying to each other. Then I thought that would be a good scene, so I went home and wrote that.”

The play leaps through time and space. One moment, the women are playing old hand games and the audience is pulled back to that schoolyard promise of ritual and belonging. The next moment, we are in a newly opened cafe where the friends have transformed into new residents who, over casual conversation, refer to Harlem with unfamiliar names like SoHA.

Naming and renaming is a huge thematic focus throughout the performance. One of the key signs of a gentrifying neighborhood is the re-designation of traditional neighborhood boundaries and names, which real estate developers rebrand to encourage new residents to move there. Owens said the metaphor of the “killer whale” came from a desire to address these many kinds of erasure.

Though the play is about Harlem, Owen said the resounding message of this piece is meant to reach all kinds of audiences — including those in Philadelphia.

“I hope that [Philadelphians] can see themselves in this play … I live in North Philly now and I see the similarities between what is happening with Temple [University] in North Philly and what is happening with Columbia [University] in Harlem … where you have a university coming into a predominantly Black community and seeing how that changes the neighborhood.”

Owens hopes the play will spark conversation among neighbors and community members. Like the three protagonists who enact an action plan to embrace the positive change in Harlem while revitalizing and preserving the neighborhood’s rich history, Owens wants local audience members to feel a stake in the places they call home.

“I hope that you will leave the show and have discussions with your neighbors … and get involved in your respective communities,” Owens said. “In talking, you learn to understand people more, you have more empathy.”

“Renaissance in the Belly of a Killer Whale,” which was extended by popular demand, will run at the Wilma Theater through March 7. In addition to the public performances, the Wilma will host four student matinees of the play, reaching hundreds of students at Philadelphia public high schools.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.