Reflections on a Philadelphia war hero and the tragedy of the USS Juneau

Nearly 700 men from the USS Juneau lost their lives, including the five Sullivan brothers. Lt. Charles Wang was the only officer to survive.

Lt. Charles Wang surrounded by Roman Catholic High School alumni sailors during their visit to the school in early 1945. (Photo courtesy of Roman Catholic High School)

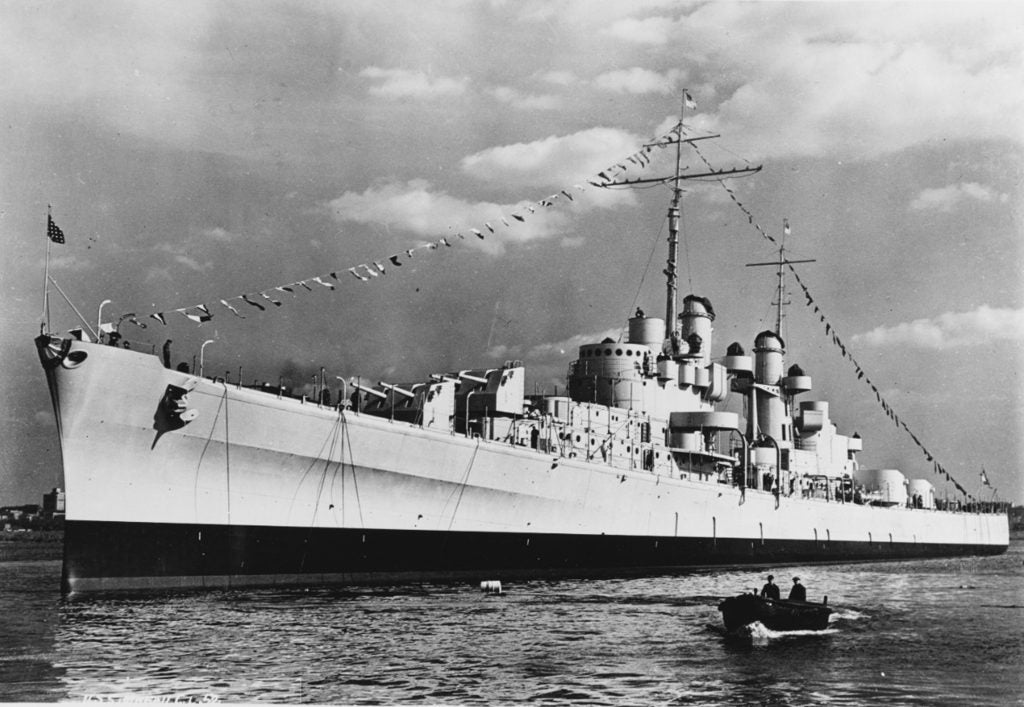

As I recently read through the various news articles that detailed the discovery of the USS Juneau by the South Pacific research exploration vessel, Petrel, on March 17, I immediately thought of a conversation with my dad several years ago. He had sparked my interest in the story of the Juneau because one of the 10 survivors of the tragedy was from his old St. Columba parish in the North Philadelphia neighborhood known as “Swampoodle” and a fellow graduate of Philadelphia’s Roman Catholic High School.

I thought that it would make for a good story someday, so I compiled a research file on the ship’s sinking. Following the Juneau’s discovery, I sorted through my file notes. I could almost hear Dad’s voice, his “straight-to-the-point” delivery style, as I read them: “They called him ‘Chick’ Wang. Lived on Lehigh Avenue. Graduated from Roman in ’34. Quarterback. Class president. Naval officer. Became a doctor.”

I remembered thinking at the time that he never mentioned the Juneau, and that, if I researched the story, I might be able to reveal some things about the tragedy that my dad did not know. It was at that moment that the memories from that conversation, as well as my earlier research into the story of the Juneau, came flooding back.

As chronicled in Dan Kurzman’s riveting book, “Left to Die: The Tragedy of the USS Juneau,” on the morning of Nov. 13, 1942, Lt. Charles Wang, torpedo officer, had just finished inspecting the damage sustained by the ship during battle the previous night. Although the Juneau had taken some hits, she could still fight, and her crew had performed admirably. Wang was resting at his station, eating a sandwich, when “a panicky voice cried into the earphones, ‘Fish! Torpedo heading toward us!’ Seconds later, at 11:01 a.m., Friday the 13th, it smashed into a magazine, and the Juneau blew up.”

Wang was thrown onto the deck by the explosion. As he lay on his back, he opened his eyes and saw the radar antenna “spiraling straight down toward him.” It smashed into his right leg, breaking it in two places, his bones protruding through the skin. Wang managed to make it into the churning water and held on to floating nets from the ship.

Many of the survivors, most badly wounded, clung to the nets as well. Others found rafts or simply floated in their life preservers. These survivors eventually consolidated into a large floating group, desperately hoping for a rescue that would not come. As night fell, the wounded began dying, and the despairing cries of sailor George Sullivan could be heard in the darkness as he searched for his four brothers. “Al, where are you?” he repeatedly cried out as tears streamed down his face. “Red, Matt, Frank, answer me! Where are you? It’s your brother George.”

The following morning, the sharks began circling. Screams pierced the air as the sharks tore into the sailors still clinging to the nets. As the days went by, the initial group of about 150 slowly dwindled to a handful. The badly injured Wang was in a state of delirium from the pain. Two sailors volunteered to try to take him on one of the rafts to the island of San Cristobal some 55 miles away, as the large flotilla of survivors was making “little headway because of the waves and the drag of the nets.” If they made it, they would try to send a rescue ship for the survivors. Lt. John Blodgett agreed, and the men set off for the island.

The next several days tested the limits of human endurance. The blistering sun burned the skin off of their backs, as extreme hunger and thirst drove some to madness. Some drank seawater, and dove underwater to imaginary “havens” where the sharks finished them off. A despondent and unstable George Sullivan told the group that he was going “to get some buttermilk and something to eat.” He swam away before anyone could grab him, and the men soon heard his pitiful cries of “Help me!” as the sharks tore into him.

Only seven men from this larger flotilla of survivors would be rescued. On Nov. 19, a PBY seaplane picked up five of the men, and the USS Ballard retrieved the remaining two the following day.

Wang and the other two sailors, in a remarkable feat of seamanship, eventually reached San Cristobal on Nov. 19 where they were rescued by islanders. The unbearable pain Wang endured while still helping to navigate the raft to safety endeared him to the two sailors who were with him.

“The courage that man showed during those days was something to behold,” one of them said.

A total of 687 men from the USS Juneau lost their lives, including the five Sullivan brothers. Only 10 men survived the sinking. Lt. Charles Wang was the only officer to survive.

In 1947, Wang married his sweetheart, Marie, at St. Stephen’s Catholic Church in Philadelphia. The parents of the Sullivan brothers were special guests.

The Wangs raised three daughters — Celeste, Deborah, and Patricia — and Charles went on to a successful medical career as a pathologist. After enduring years of excruciating pain, he finally had his damaged leg amputated in 1980. Wang died in 1985 at the age of 70. He was chosen as one of Roman Catholic High School’s “125 Men of Distinction” in 2015.

I asked my dad if he ever met Charles Wang.

“Once. I was just a kid,” he answered. “He came back to Roman during the war. He said that if any of us ever went to war, to try not to be afraid, do what you’re told, and listen to your officers.”

My dad’s eyes then welled up, and his voice cracked as he vacantly stared at a distant memory that only he could see.

“He was on crutches … his leg was bad. He told us what happened.”

It was at that moment that I realized there was nothing I would discover in my research of Charles Wang and the brave crew of the USS Juneau that my dad didn’t already know.

—

Chris Gibbons is a Philadelphia writer. He can be reached at Gibbonscg@aol.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.