RDA vacant land report released

A new, 94-page report, “Vacant Land Management in Philadelphia: The Costs of the Current System and the Benefits of Reform,” was released today by the Redevelopment Authority of Philadelphia (RDA) and the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations (PACDC).

The study examines the continued financial burden and untapped development potential present in the estimated 40,000 vacant parcels that dot the city.

According to Brian Abernathy, Chief of Staff in the Managing Director’s Office, the City wants to “create a uniform and transparent way to deal with vacant properties.” The report, he says, is a start to understanding the scope and impact of the problem.

Previous PlanPhilly vacancy coverage

Among its key findings is just how greatly vacant parcels affect all of us by lowering the value of our property. The report estimates that, citywide, blighted land accounts for a $3.6 billion loss in property values, or an average of $8,000 per household. Proximity to a vacant parcel reduces home values by an average of 6.5% citywide (with some neighborhoods averaging closer to 20%), according to a formula that evaluates a housing unit’s positive and negative characteristics, traits, and amenities.

“We weren’t expecting the impact numbers to be as great as they are,” says the RDA’s deputy executive director, John M. Carpenter, Jr. “This problem is clearly not just about the most devastated neighborhoods,” he continues. “It has a personal impact on any block on which there’s even a single vacant property.”

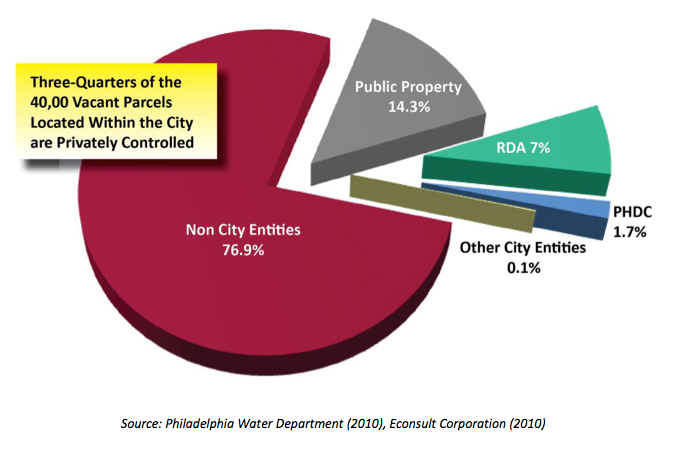

The report was jointly prepared by Econsult, the Penn Institute for Urban Research, and May 8 Consulting. It uses Philadelphia Water Department records, which define as vacant those parcels which no longer receive water service, to arrive at its total of 40,000 vacant properties. Concentrated mostly in North and West Philadelphia, these parcels add up to 3,555 acres, valued at nearly $2 billion, estimate the researchers. The great bulk — 37,000 — of these parcels are entirely structureless. More than three-quarters (31,000) remain in private hands, while the City controls just 9,000 parcels.

This is another critical element of the portrait, according to Carpenter. “A lot of people will be surprised,” he says. “So often the conversation focuses on ‘why can’t the City do a better job of marketing empty land’?”

The report notes, however, that the City’s historically decentralized approach to vacant land management has contributed to the problem. It goes on to observe that “a strategic and coordinated response by the City could substantially reduce the negative effect of vacant parcels, and transform them from liabilities to assets,” but doesn’t offer specific recommendations.

It does call for consideration of a comprehensive land management system like those employed in Baltimore and Cleveland, among others. Instead of recommendations, the report builds a case for the importance of examining the impact of neglecting the problem, and the potential benefits of dealing with it.

First, it provides a thorough breakdown of the absolute financial cost of such properties to the City and its citizens. Aside from the dramatic property value loss associated with vacant land, the report names two other impacts: maintenance costs and uncollected property taxes.

Based on interviews conducted with department representatives, a review of available financial statements, and research on equivalent per‐capita costs from similar nearby localities, it conservatively estimates that the aggregate maintenance costs tally more than $20 million each year. Municipal money spent on servicing these lots ranges from almost $6 million on fire and police department responses to $390,000 for work related to Streets department removal of waste. In all, 17 city agencies or related entities bear costs associated with the maintenance of vacant parcels.

Uncollected property taxes could potentially add $2 million to City and School District coffers each year. It’s a relatively small number since about two-thirds of the estimated 17,000 vacant parcels that are tax delinquent have been so for more than ten years. The bulk of the total $70 million in taxes, interests and penalties owed is thereby considered uncollectible.

Aside from the reduction or elimination of these costs, reform will lead to other benefits, of course. Chief among them is more and faster development, achieved by making the land acquisition process more efficient, by assembling adjoining parcels for greater development opportunity, and by aggressively marketing and pricing those parcels.

Another benefit is new housing. The report estimates that there are about 3,400 vacant parcels located in Census tracts where current house prices exceed construction costs plus a 10 percent profit for the developer, thus making them feasible to be built on. The report equates each parcel with one housing unit. It notes that the Philadelphia City Planning Commission projects that the City will experience a net increase of 46,000 housing units by 2035 and that it “does not seem unreasonable” to imagine a solution to the problem of vacant land would help meet that need, or exceed it.

Besides additional housing, such building results in fiscal impacts such as revenue generated from increased wage, sales, and business privilege taxes related to construction activity, taxes associated with real estate transfers, and new property, wage, and sales taxes from the added residents. These numbers total more than $37 million over a five-year period that represents the first round of reusing now-vacant land.

In an appendix, the report presents others ideas on what to do with land, including converting parcels to permanent open space and leasing them for urban agriculture. Ultimately, the report goes on, the “actual number of parcels developed in any given year will depend on a number of factors, including where in the business cycle the local and national real estate markets are, whether the City is adding residents and wage earners or losing them, and what construction costs and house prices are doing within the city and within competing markets.”

The upshot, says Abernathy, is “we have a problem, and we have to fix it. That’s not a secret — we all know the devastating impact that vacant property has on our quality of life. This report, though, presents a very solid look at just how wide-ranging the economic impact is.”

Abernathy says that now that the report is in hand, the next step is for the Vacant Property Working Group, chaired by Managing Director Rich Negrin and Finance Director Rob Dubow, to present recommendations to Mayor Nutter.

Through the rest of this year and early next year, the group will continue meeting with developers, CDCs, and City Council and State officials. “These stakeholders all need to have a say,” Abernathy says. “Not just because if we don’t engage them, we can make mistakes, but because we don’t want to lose their buy-in.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.