Racism left Hunting Park overheated. Neighbors are making a cooler future

The North Philly neighborhood has fewer trees and hotter days than areas that weren’t redlined. Residents, along with city government, are working on solutions.

Listen 4:18

Tayon Whiting delivers fans to residents in need on 10th Street. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Tayon Whiting’s beard, black and gold face mask and bald head were drenched in sweat on a sweltering August afternoon as he walked down a treeless Hunting Park block.

For three straight days, the temperature had soared over 90 degrees in the North Philadelphia neighborhood and Whiting, who had just finished delivering free food to some of his neighbors, now was lugging a brand-new box fan in each hand to give to elderly residents. Employed by the Lenfest Center, a local nonprofit community center, he spends his days checking in on at-risk neighbors to see what they need.

“Heat affects my community pretty seriously cause not everybody has ACs and fans and stuff,” said Whiting, 38, who grew up in Hunting Park and is now raising his own children there. “Heat prevents them from coming out, getting all this produce that we have, and some people can’t stand the heat. They need to be in cool temperatures.”

Extreme heat is a top health concern in Philadelphia. Over the past 14 years, there have been 139 heat-related deaths citywide, according to city records. Nationally, heat kills more people than hurricanes, tornadoes or flooding, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Seniors, young children and people with pre-existing health conditions are at a higher risk of heatstroke and heat exhaustion, which can be deadly.

In the ’90s, the city pioneered a heat response system that significantly reduced the death toll of sweltering city summers. But Philadelphia and other urban areas are registering a growing number of hot days each year. In July, the city observed 21 days with temperatures at 90 degrees or higher — that’s three more days than last year and 10 more than average. By 2030, the number of days with temperatures equal or greater than 95°F is expected to double in Philadelphia.

The heat is impacting low-income neighborhoods and communities of color disproportionately. Areas such as Hunting Park, where residents are predominantly Hispanic and Black, have surface temperatures as much as 22 degrees higher than in leafier areas of the city.

Hunting Park, like other working-class neighborhoods across the country, has fewer trees and green spaces than richer and whiter districts, more pavement and exposed asphalt, and more older buildings, most of them with dark rooftops, all of which contributes to higher temperatures, or what’s known as the “urban island heat” effect.

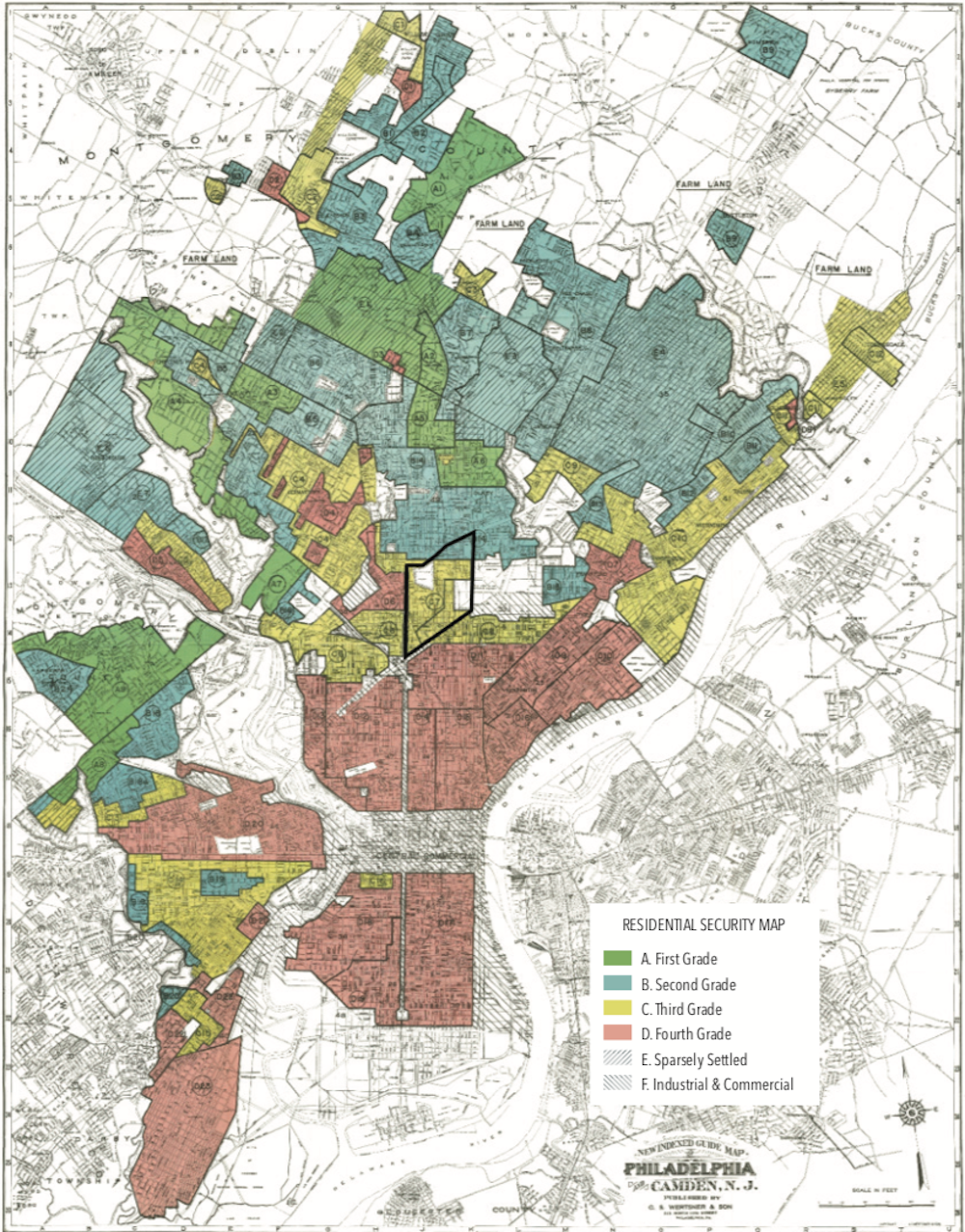

Philadelphia officials recognize that’s largely due to redlining and other discriminatory practices applied by banks and some government agencies, which led to decades of disinvestment in low-income districts across the country, making it harder for residents to invest in their properties and prosper economically. Many of the areas shaded in red and yellow on the 1940 Home Owners Loan Corporation map and classified as “high risk for lending” because they were populated by immigrants and people of color are today highlighted on city maps for their vulnerability to heat. Hunting Park falls into that category.

“For us it became clear that, as temperatures get hotter, some neighborhoods are going to suffer more than others,” said Christine Knapp, who heads the city’s Office of Sustainability.

For that reason, it made sense when, two years ago, the city selected Hunting Park for a heat mitigation pilot plan. The “Beat the Heat” initiative, known as Venza el Calor in Spanish, seeks to address the causes of heat inequities, and a “heat team” composed of government departments and community organizations joined forces to come up with solutions.

They started out by surveying over 600 residents to find out how much their lives were being impacted by the high temperatures. The results, published last year, helped officials understand what the community needs and how best to help. The team concluded that a top priority should be “cooling centers,” air-conditioned public buildings such as libraries, where people could take refuge on extremely hot days. Since Hunting Park has no library, community organizations and churches were identified as potential cooling centers. That initiative was set to start this summer.

“And of course, COVID-19 hit in March and sort of threw that plan off,” said Knapp.

The coronavirus pandemic caught Philadelphia with no real solution for the most heat vulnerable. During a heatwave in July, city officials suggested that residents without air conditioning seek relief at the homes of neighbors with AC units, despite a stay-at-home order. But many balked.

Henrietta Washington, a 69-year old retiree who lives alone in a house built in 1900 that has no air conditioning, is asthmatic and suffers from knee problems. It doesn’t stop her from being active, but she says she wouldn’t go to any neighbor’s house right now, because of COVID-19.

“I don’t know where the friend’s been and who they’re around. I’d rather stay home and have the fan blow on me,” she said.

Problem is, she only had one fan, and on extremely hot days, her two-story house felt dangerously hot. That’s when Whiting showed up with a free fan. It’s one of 100 fans that the team distributed to senior citizens in the month of August alone.

“It’s really been hot,” she said while happily accepting the box fan at her door. “I’m glad that this sinner thought about us,” she said, making Whiting, who she’s known since he was a child, laugh. “We seniors need somebody to think about us.”

Whiting came to her door as part of the city’s first-ever ‘Heat Team,’ a coalition of community organizations, city agencies and other institutions working in the initiative.

In August, he helped distribute about 100 fans and 15 air conditioning units to elders like Washington who he said practically raised him.

“They came out and said ‘Tayon, we want to provide fans for the community, we need to know who needs them the most.’ So I said, OK,” Whiting said.

Keeping cool in a ‘cooling center’

On a hot Thursday afternoon in August, members of the heat team set up a folding table and a tent at the Lenfest Center’s parking lot and asked people who were arriving to pick up free milk and produce if they would complete a survey.

Team member Bernadette Mason, a 40-year resident of Hunting Park, convinced Diana García and her father, Aladino, to fill one out in exchange for a “heat kit” — a paper bag with sunscreen, hand sanitizer, and tips on how to stay cool — and a chance to win a $50 gift card.

García, 48, was happy to answer the questions. She read them out loud in Spanish so that her father could understand.

“Would you go somewhere to stay cool?” Mason asked them, explaining one of the questions. “Would you be interested in going to a cooling center?”

The Garcías had never heard of cooling centers, but they said if one were available close to their home, they would go. They can’t afford air conditioning; all they have is a small fan. Diana worries about her father’s health, but he says he’s fine.

“Yo me tiro al agua, como cuatro veces al día — al agua fría!,” García, a Puerto Rican native in his 70s, said laughing. “I jump in the shower something like four times a day, in cold water.”

With many public buildings closed, The Lenfest Center planned to help by offering the shade of a big tree as well as tents and benches. The nonprofit purchased misting fans to keep people cool.

“We don’t have a lot of trees on our block, and if you could see kind of a top-down look, a lot of our neighbors have black roofs. And so, with the black top and the non-porous surfaces, it just stays hot all the time,” Chris Gale, the center’s director, said. “So whenever we have a heat emergency in the city, Hunting Park definitely feels the heat here.”

Many residents needed more than cooling centers and electric fans to keep the heat at bay. Providing energy-efficient air conditioning units and grants for residents to afford the bills is essential.

“Almost everyone wants to stay home when it’s hot outside,” said Cheyenne Flores, a climate resilience fellow with the city’s Office of Sustainability and the Beat the Heat field coordinator. Yet, while 84% of residents surveyed said they have an air conditioner at home, nearly half of them reported that they don’t always use it, even on hot days, for fear of running up a big electricity bill.

The team has installed some donated AC units in local homes and plans to buy 20 more, paid for by two community organizations. But Knapp, the Office of Sustainability chief, says the city can’t afford massive AC giveaways like New York City, which offered 74,000 units to low-income seniors this summer. She had hoped that the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission would approve $1.5 million to replace old AC units with new, energy-efficient ones for customers with household incomes at or below twice the federal poverty level. But that proposal was turned down in August after some commissioners argued the expenditure could raise other customers’ electric bills.

One of the people who did receive a donated AC unit was Vernetta Santos, a 44-year-old Hunting Park resident who depends on disability benefits. Santos, who sports a flower tattoo and another that reads “MOM” on her forearms, lives with three of her five kids. All of them have asthma, which is triggered when it’s extremely hot.

“We’ll start to wheeze, coughing, can’t sleep at night … Then we have to use the nebulizer machine or the asthma pump,” she said.

Before receiving the new unit, Santos had three old ACs. But she said her house remained overheated during excessive heat. “The new air conditioner blows cool air — it’s keeping the house cool,” she said.

Through Beat the Heat, Santos learned that the state’s Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which normally provides assistance for residents’ heating costs during the winter, also was offering help with cooling-related bills this year.

In the long run, the best way to make Hunting Park cooler is to plant more trees. As it is now, the neighborhood is a tree desert: they cover less than 7% of its surface, compared to an average of 20% in the rest of Philadelphia. The lack of shade means that streets and sidewalks retain and radiate heat into the evening.

Beat the Heat is working with the city’s TreePhilly program and the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society to increase the number of trees in the area. The Hispanic community organization Esperanza has planted about 800 trees over the last eight years. Philadelphia’s goal is to reach 30% tree coverage citywide in the next five years, with a special push in low-income zones.

In the meantime, local agencies and researchers are coming up with measures to provide relief until the leaves can do the work.

Seven municipal buses were used this summer as temporary cooling centers throughout the city. Census takers were tasked with asking residents if they needed information on government resources for heat relief. The city parks department deployed tents, umbrellas and water toys in some of its hottest neighborhoods through its PlayStreets program.

Drexel University engineering professor Franco Montalto designed a pilot program to make the city more climate-resilient, as part of his collaboration with the federal government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Consortium for Climate Risk in the Urban Northeast.

The program aimed to cool off a one-block section of North Marshall Street in Hunting Park by installing physical shade structures, and bringing in plants and water sprinklers. The idea is to shade and wet paved areas so that they don’t get as hot.

“The sprinklers were a real hit,” Montalto said. “People were calling their relatives to come to the block because the block became essentially a big spray park.”

Montalto said low-cost projects like this can compensate for the lack of access to air-conditioned spaces during the pandemic. They also involve residents in the process by hiring them to monitor surface and air temperature and humidity, take care of the infrastructure and log the way it’s being used.

If the experiment works, Montalto hopes to expand it to other neighborhoods next summer. So far, he’s optimistic. On a preliminary reading, the temperature of pavement with no shading, no greenery and no sprinklers reached 112 degrees, but the temperature of pavement in the pilot area with just the sprinklers measured only 80 degrees.

“That’s a 32-degree difference,” he said, his excitement evident.

As Philadelphia and other big urban centers continue their search for long-term solutions to rising temperatures, members of the Beat the Heat team are convinced that community education, emergency cooling stations, and some form of government assistance for energy costs are the best bet for short-term relief.

Montalto said having the Heat Team has been crucial to make the project work.

“It’s a really interesting local governance body,” he said.

Bernadette Mason, the resident taking surveys outside of the Lenfest Center, agrees.

“It’s a work in progress,” said Mason, as she surveyed residents outside the community center. “Next year we hope to really do a little bit more, and each year, to just keep it up until we can say we have the trees, we have cooling stations, we have partnered with other companies and organizations that can help us out.”

This article was published in collaboration with Palabra, a multimedia journalism platform created by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ).

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.