Racial differences in COVID mortality rates linked to unequal hospital quality, Penn study shows

Researchers looked at 10 months of data from more than 44,000 Medicare patients from 1,188 hospitals in 41 states and the District of Columbia.

In this Nov. 19, 2020, file photo, a registered nurse works on a computer while assisting a COVID-19 patient. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

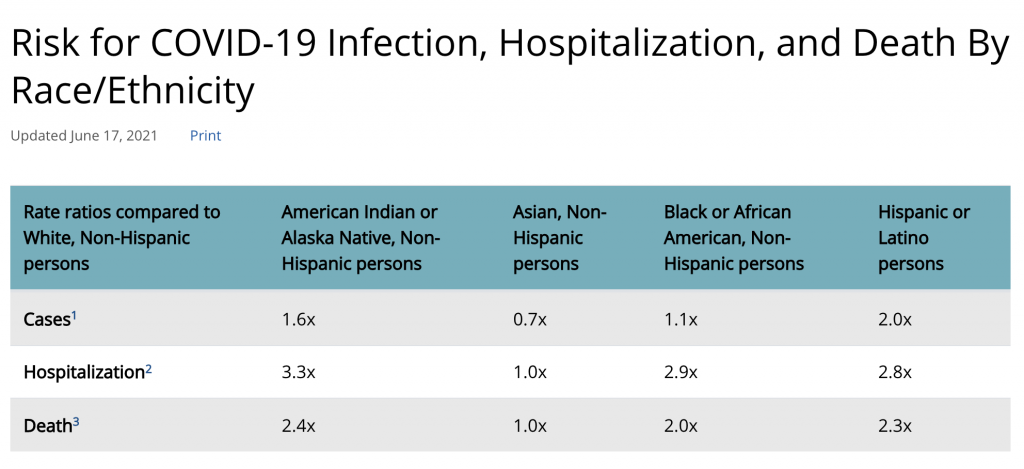

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, clinicians and health systems have observed noticable differences in COVID-19 outcomes by race. According to recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American communities are more likely to contract the coronavirus, to be hospitalized because of the virus, and to have an increased risk of death from the virus when compared to their white counterparts.

David Asch, executive director of Penn Medicine’s Center for Health Care Innovation, says he and his colleagues had conducted studies showing how the kind of hospital a person was admitted to could determine how likely the person was to recover from the virus.

“And we wondered whether that same phenomenon might help explain why there were racial differences in mortality,” Asch said.

In other words, was it possible that Black patients did worse than white patients because they were admitted to hospitals that provided worse care for all?

Recently, that’s what Asch and a team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and OptumLabs found. They examined hospital-level differences by looking at 10 months of de-identified hospitalization data from more than 44,000 Medicare patients from 1,188 hospitals across 41 states and the District of Columbia. After observing inpatient mortality rates in the 30 days after admission for each racial group and including those discharged to hospice care, the study showed that the overall mortality for white patients was approximately 12.9% and 13.5% for Black patients.

According to Asch, inpatient mortality or discharge to hospice was 11% higher for Black patients than for white patients after adjustment for patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

So the difference between living and dying boiled down to which hospital a person had access to in the community, and sometimes the distance between the underresourced and overresourced hospitals was just a matter of a few blocks.

“Patients who are Black are much more likely to come from poor neighborhoods,” said Asch, the study’s first author. “Patients tend to go to hospitals that are near them, and therefore Black patients are more likely to go to hospitals that are underresourced. It’s a story of inequity, it’s a story of structural racism that has its origins centuries in the past.”

Hospitals receive their funding largely based on the kind of insurance the patients in their communities have, Asch said. A hospital in an area where many people are uninsured or on Medicaid — whose reimbursement rates for medical services are much lower than for Medicare and commercial insurance — has far fewer financial resources with which to take care of patients.

And the likelihood that a hospital is serving a predominantly low-income, underinsured community is racially distributed in this country. Which means hospitals that predominantly serve patients of color will continue to receive fewer resources under the current health care system.

“We have a patchwork system of health insurance in this country, and one of the net effects of that system is that you make more money taking care of white patients than you make taking care of Black patients,” said Asch. “And that will inevitably underresource those doctors and hospitals that take care of largely Black populations.”

Typically, doctors and researchers have attributed racial differences in COVID-19 mortality to a higher prevalence of chronic illnesses in Black communities. Asch said increased mortality among Black patients was partly explained by lower income levels and more comorbid illness in those populations. But the new study also found that if Black patients went to the same hospitals white patients went to in the same distribution, the Black-white mortality difference would disappear. In other words, the quality of the hospital had a greater impact in determining a patient’s mortality than the patient’s own underlying conditions.

“When you adjust for something like how much hypertension was in the population, you do find that that helps explain some of the racial disparities that we see in COVID outcomes,” said Asch. “But does it excuse the difference? Society has created a set of circumstances that relentlessly disadvantaged Black Americans, and some of those circumstances lead to increased hypertension, lead to increased diabetes, and lead to increased obesity.”

Asch cautioned health researchers and clinicians from simply explaining away racial differences in mortality by citing underlying conditions. Instead of blaming the symptom or circumstance, he said, doctors should look at themselves and their health systems for perpetuating health disparities.

Rachel Werner is the executive director of Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and a study co-author.

“Research has shown that where Black patients get their care is much more important, and that if you account for where people are hospitalized, differences in mortality vanish.”

Asch said the next step toward a more equitable health system could happen with sweeping policy changes such as implementing universal health care or increasing reimbursements rates for Medicaid so they are more aligned with Medicare and commercial insurance rates.

“It’s intolerable that we live in a society where Black patients are more likely to go to hospitals where death is more likely,” said Asch. “Centuries of racism got us to this level of residential segregation, but a step we can take today is to change policies so that all hospitals are not so dependent on local resources to maintain their quality.”

“COVID-19 has provided a lens through which we can see how much more we must travel to reach justice,” he said.

—

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)