Is Princeton’s Paul Robeson house trying to tell us something?

-

Sandal (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Glass jar (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Beecham pills (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Bottle (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Broken toy (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Brush (Photo by Wendel White)

-

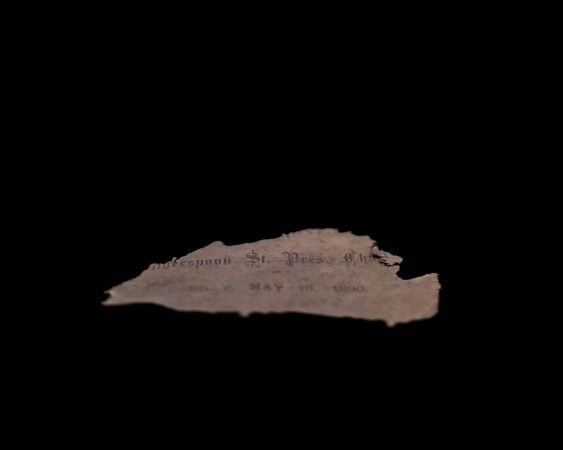

Church (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Corked bottle (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Embroidered cloth (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Fish (Photo by Wendel White)

-

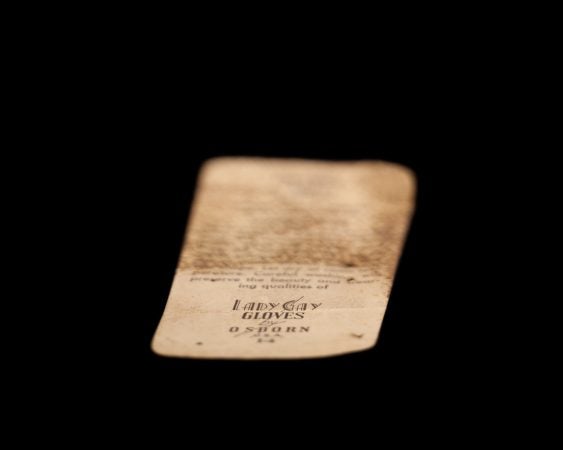

Glove (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Glycerine (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Ice cream label (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Tin can (Photo by Wendel White)

-

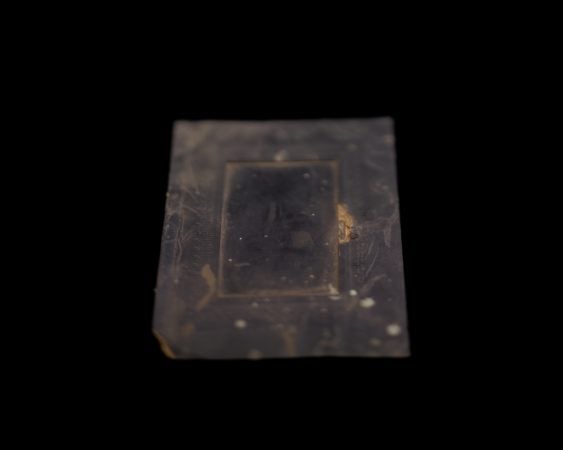

(Photo by Wendel White)

-

Key (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Tag (Photo by Wendel White)

-

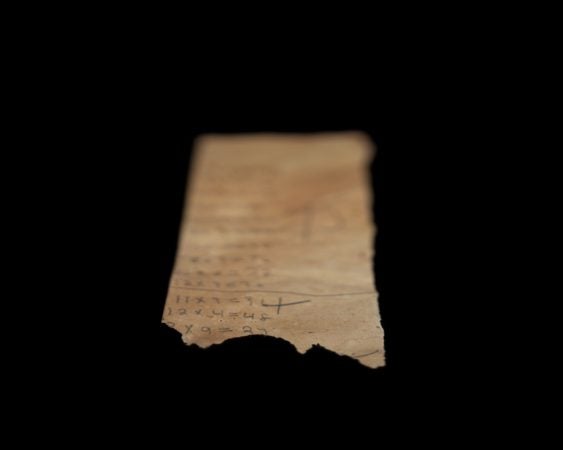

Math work (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Letter (Photo by Wendel White)

-

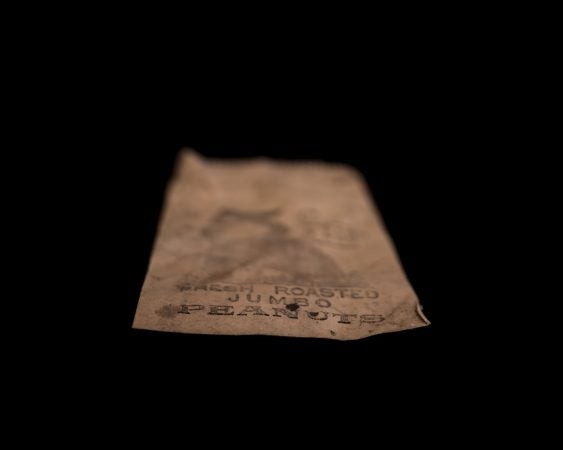

Peanuts label (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Pen (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Horses (Photo by Wendel White)

-

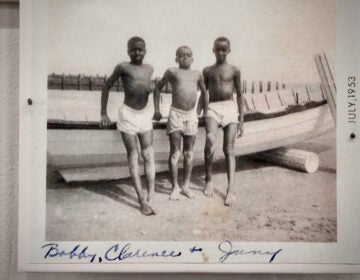

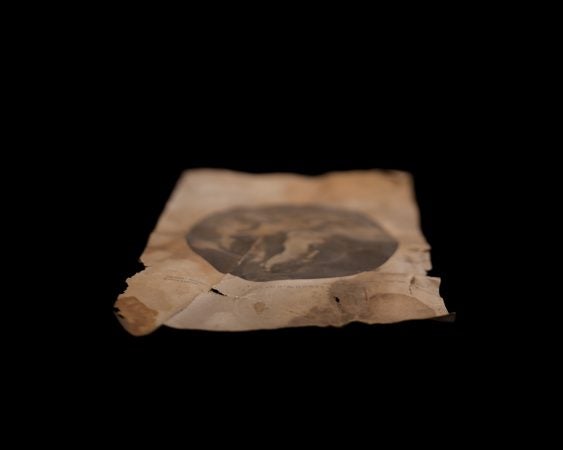

Photo (Photo by Wendel White)

-

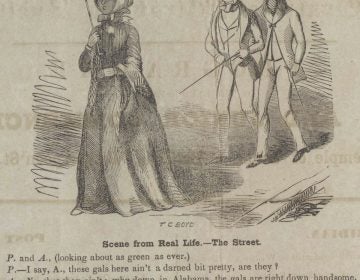

Card (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Shirt sleeve (Photo by Wendel White)

-

House shoe (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Envelope (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Paper frame (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Tobacco pouch (Photo by Wendel White)

-

Tobacco pouch (Photo by Wendel White)

The sandal, encrusted with a fine layer of grit, looks like it’s made of stone. A tin of Beecham’s Pills from St. Helen’s, Lancashire, England, “Sold by the Proprietor” and with the paper wrapping intact, is so old, the price — 25 cents — is not stamped on but integrated into the label design.

These and other artifacts were unearthed during renovations of the Princeton, N.J., house where Paul Robeson was born. Photographed against a stark black backdrop by Wendel White, they are being projected against the façade of the house, across the street from the Arts Council of Princeton, from dusk to 9 p.m. through November 30 as part of the exhibition Reconstructed History. These artifacts tell the stories of the African-Americans who lived in this house over the past century.

It all began when volunteers gathered in the house to do demolition, and a piece of paper that had been wedged between floorboards for more than a century fluttered from the ceiling. “It was as if someone were reaching out” from beyond the grave, said architect Kevin Wilkes, who volunteers his services on the restoration — plans call for it to become a center for the study of human rights and a testament to the Robeson family.

The artifacts — basic items from everyday life, such as matchbook covers, thimbles, combs — were left behind by the many African-American day laborers who lived in the house over the years and are like “a piece of the past speaking to us,” said Wilkes, and, at a time when the nation is still reeling with issues of racism, it is a frank reminder of Princeton’s Jim Crow-era past.

Facing a beautifully landscaped cemetery where many notables are buried, from Silvia Beach and John O’Hara to Aaron Burr Jr., Grover Cleveland, and Michael Graves, as well as Paul Robeson’s parents, the aluminum-clad gabled house might go unnoticed were it not for the bronze plaque identifying it as the birthplace of the actor, singer, and political activist. On the state and national historic registers, the 1,922-square-foot house is where Robeson (1898-1976) was born. The house came with his father’s job — the Rev. William Robeson, who at 15, escaped slavery on a North Carolina plantation, served as minister of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church a few doors down.

That piece of paper that fell from the ceiling turns out to have been a trolley pass that had been issued to Paul’s brother, Bill Jr., who had to commute to high school in Trenton when Princeton High School was white only.

In Jim Crow-era Princeton, African-Americans who worshipped at Nassau Presbyterian Church had to do so from the balcony. When a fire destroyed it in 1839, the church funded construction of the Witherspoon Presbyterian Church in the historically black Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood. Known for his advocacy of civil and human rights, William served 20 years in the pulpit.

Paul inherited his father’s oratorical skills. “William drilled his children in Latin and Greek at the Sunday dinner table,” says Wilkes. Paul would go on to speak 15 languages. Denied admission to Princeton University because of his race — despite vehement protests from his father — brother Bill went on to earn a bachelor’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania and an M.D. from Howard University College of Medicine.

For speaking up about civil rights issues, William was ousted from the church, and the family had to vacate the house. They moved further down Green Street, where Paul’s mother died in a kitchen fire, then settled in Somerville, N.J. The church fell on hard times and had to sell the property. It became a boarding house for day laborers and, at one time, there was a barbershop on the lower floor of the Robeson house and a lounge where workers from Princeton University’s eating clubs would gather.

In 2005 the church bought the property back from a parishioner. The New Brunswick Presbytery, responsible for ousting William, apologized and, as a gesture of recompense for what it termed “ecclesiastical lynching,” retired the mortgage.

The Robeson House Committee formed in 2007 with plans to restore the house. Plans call for a public meeting room, gallery space for historic interpretation, offices for nonprofits, and three apartments.

The Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood was designated an historic district by the township in 2016. The Arts Council building, also known as the Paul Robeson Center for the Arts and situated on Paul Robeson Place, once served as the black YMCA. Princeton’s “Colored School” was around the corner, on Quarry Street.

Curator Amy Brummer, who read a newspaper article about the trolley pass, came up with the idea of having Wendel White photograph the house’s uncovered artifacts. Brummer was familiar with photographer White’s Schools for the Colored Series collection, in which he uses medium format film to show images of buildings or locations that were designated as such, and his Manifest portfolio of images of objects from African-American material culture — diaries, slave collars, human hair, a drum, and quotidian representations of ordinary life. Brummer conceived of White’s photographs of the Robeson artifacts for the exhibition Reconstructed History, which led to White becoming the Fall 2017 Artist in Residence at the Arts Council.

Photographed in the style of his Manifest portfolio, these items “seek out the ghosts and resonant memories expressed in various aspects of the material world,” said White, a professor of art at Richard Stockton College. White has also created a series of portraits of black towns in southern New Jersey.

In order to become the center that its non-profit board envisions, the Robeson house needs to raise funds, and Brummer, White, and Wilkes hope this exhibit will bring attention to the house and its important place in Princeton history.

White’s Manifest photographs of the Paul Robeson house objects will remain on view inside the Arts Council building through December.

___________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.