Princeton to air out its own legacy of slavery

The Princeton & Slavery Project, a website of research documenting the university's historic record of slavery, will host a symposium on campus this weekend.

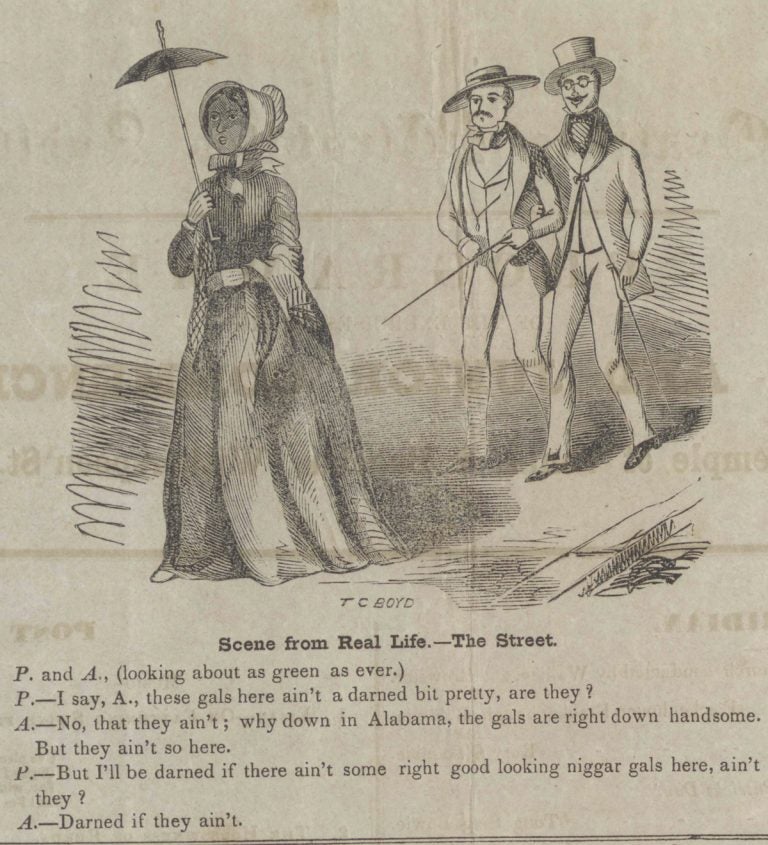

Cartoon from a student newspaper, The Nassau Rake, depicting two white men commenting on the attractiveness of black women in Princeton, June 29, 1853. (The Princeton & Slavery Project)

If a historian would take a hard look at almost any American institution going back 200 years or so, it’s likely slavery will pop up somehow. It’s one of the shameful facts of American history.

Princeton University was unique among the nation’s early universities because it was a northern school that attracted a lot of students from the South. Before the Civil War, about 40 percent of the students were from southern states, according to historian and professor Martha Sandweiss.

“We needed those southern students here. We relied on their tuition money,” she said. “So the president and faculty on campus created an atmosphere where you didn’t talk about this stuff much. You tried to keep the peace, so southern boys and northern boys could co-exist in peace.”

Sandweiss spearheaded the Princeton & Slavery Project, in which students pored through the university archives asking two basic questions — who owned slaves and whose money came from the institution of slavery. Their results are now published on a website featuring 90 stories backed up by 370 searchable primary sources, illustrated with interactive maps, graphics, and videos.

Since the site launched last week, more than 10,000 people from 95 countries have visited to delve into Princeton’s complex legacy of liberty and slavery.

This weekend, the Project is hosting a symposium to discuss its findings

The school — then called the College of New Jersey — was founded before the American Colonies won their independence as a nation. The patriots fought — and won — a Revolutionary War battle. In 1783, the Continental Congress met on campus.

Almost simultaneously, when university president Samuel Finley died in 1766, his possessions were auctioned off in front of the president’s mansion on Nassau Street. That included the sale of his five slaves.

The students working on the Princeton & Slavery Project dove into research on one of the university’s early donors, Moses Taylor Pyne, whose enormous financial support of Princeton transformed the campus at the turn of the 19th century.

Those researchers followed the money.

“He was absolutely our most generous benefactor in the late 19th and early 20th century. His money helped pay for some very important buildings on our campus,” said Sandweiss. “His fortune came directly from his grandfather, a New York merchant trading with sugar plantations in Cuba — places that thrived on the backs of enslaved labor.”

The Princeton & Slavery Project has nothing to do with recent student protests calling for eradicating Woodrow Wilson’s name from campus buildings because the former president of the university and the U.S. was a staunch segregationist.

This project predates those demonstrations by a couple years. It began in an undergraduate history class, building its own head of steam.

The project is intended to be purely an academic pursuit and not a form of protest, said Sandwiess, adding that it was not commissioned by the university administration.

However, since the dramatic student sit-in at the university president’s office in 2016 over Wilson, the university administration has created a histories fund, intended for projects that examine Princeton’s legacy in relation to issues about race.

The Princeton & Slavery Project symposium this weekend is a benefactor of that fund.

“I am pleased to be participating in one of the sessions, and I expect that the symposium and the project will stimulate ongoing discussion, additional research, and a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of our history,” wrote university president Christopher Eisgruber in a statement.

The weekend symposium will also feature new artwork, a documentary film, and a series of commissioned, theatrical plays. Sandweiss said artists can present history creatively, in ways traditional historians cannot.

“Whatever conversations ensue on our campus about monuments, naming, or race, they will be very informed conversations,” said Sandwiess. “We are giving people a lot of data.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.