Photos at Princeton chronicle urban decline, and show pathways to solutions

The show features photojournalism, urban planning maps, film loops, and art photography to show how all these forms of image-making contributed to a vision of what the American city was at the time, and what it could become.

“The worst fears come true as New York’s Negro ghetto erupts.”

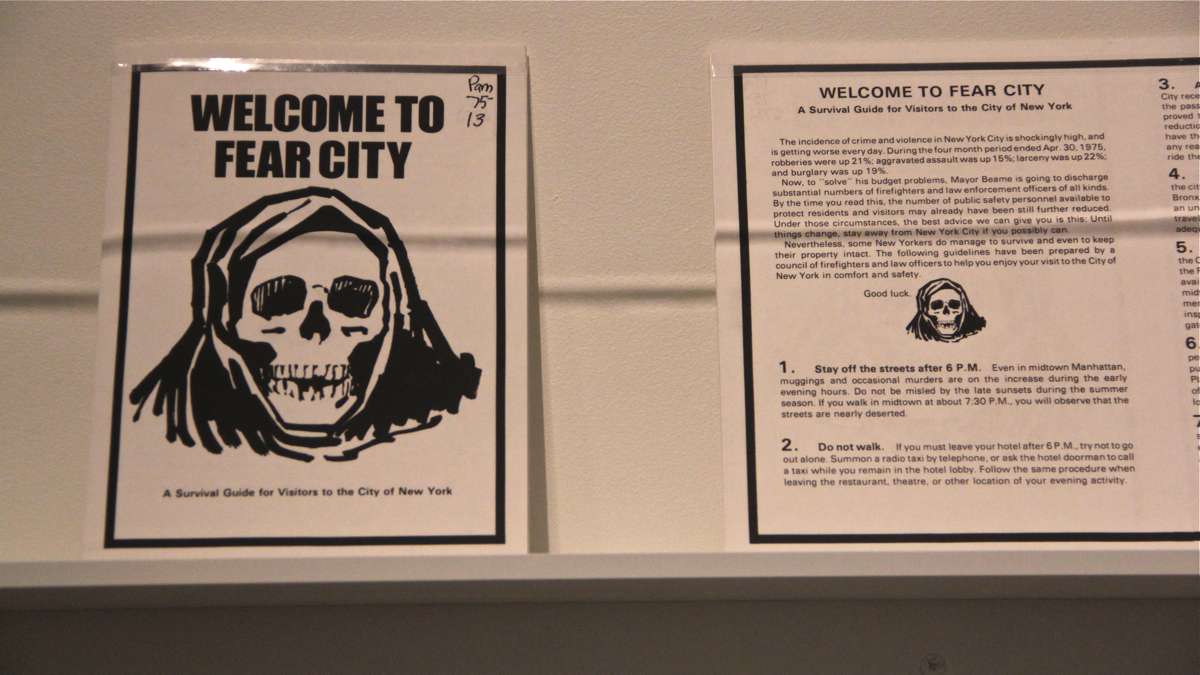

That subheading of a 1964 Life magazine article about the Harlem-Bedford riots speaks volumes about the perception of the American city 50 years ago. Here was the subtext: Cities were violent, racially segregated, and you were right to be afraid.

That tagline under a two-page photograph of protestors surrounding a black man bleeding from the head is included in “City Lost and Found: Capturing New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, 1960-1980,” an exhibit now on view at the Princeton University Art Museum.

The show features photojournalism, urban planning maps, film loops, and art photography to show how all these forms of image-making contributed to a vision of what the American city was at the time, and what it could become.

“Cities were in profound crisis during this period,” said co-curator Alison Fisher of the Art Institute of Chicago. “Not only were they unsustainable in terms of finances and decimated by the moves of industry, but the idea of encounters on the street that we prize in contemporary life – the mix of people and economies –was not seen as desirable.”

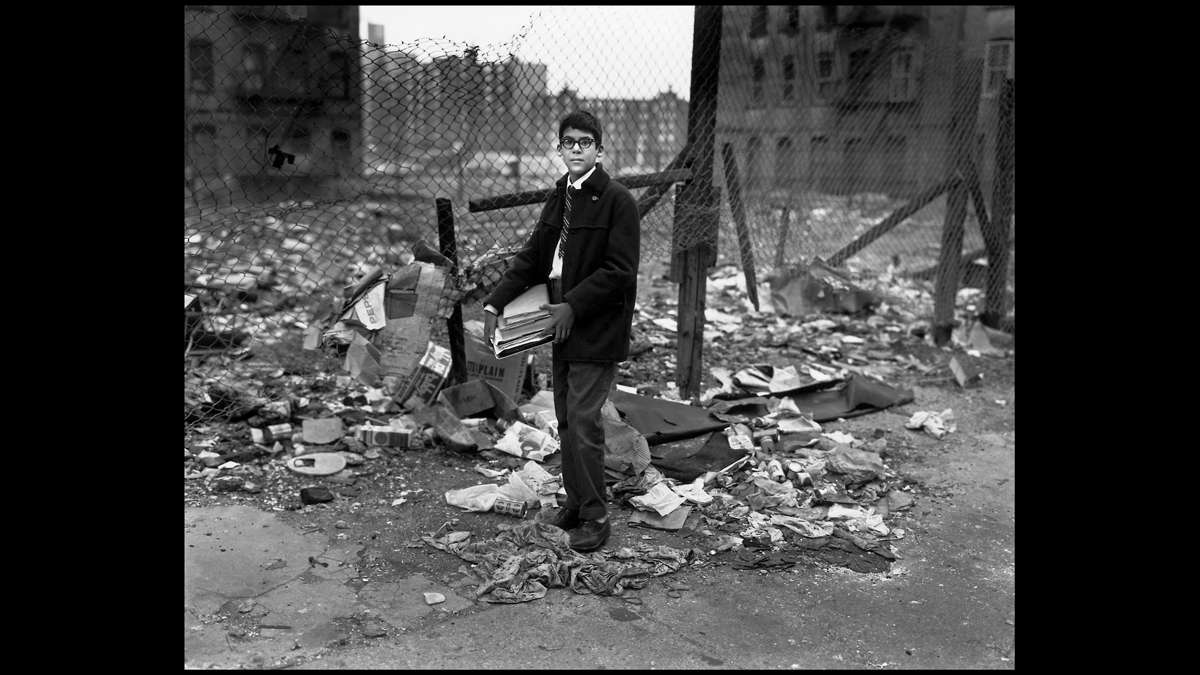

The exhibition, based on photography, has images 40 and 50 years old that seem remarkably contemporary. A slide show of New York street life by Helen Levitt from 1971 (projected via an old-school slide projector, the kind that progresses mechanically through the carousel) looks like something Zoe Strauss might have done last year. Images of urban riots, with confrontational African-American men clashing with white police officers wielding nightsticks, could be mistaken for up-to-the-minute news.

“We were sending off the final versions of our essays [for publication] – and mine in particular was about demonstration images – as Ferguson was unfolding,” said another co-curator Katherine Bussard of the Princeton Art Museum. “It was a jarring slip – how images sometimes don’t change over time.”

Some images seem plucked directly out of zombie apocalypse movies, which huge expanses of decimated, abandoned blocks. A 1975 photograph by Andy Blair shows a burned-out car alone on an empty West Side Highway in New York City.

“When you have a city that leaves abandoned cars on highways, all bets are off,” said Bussard. “A lot of creativity comes out of a response to a city in that place.”

The show goes over ground well-known to people interested in the history of American cities: Urban development plans that razed old neighborhoods for new buildings destroyed the social fabric of established communities. Highways slicing through urban center suffocated neighborhoods. White flight and industry shifting to the suburbs robbed inner cities of economic resources.

What is different about this show is how it views artists as contributors to solutions to city problems.

Alan Kaprow, the creator of Happenings in the 1960s, staged an event where people dragged furniture through the streets of New York, set it up in abandoned spaces, and spent the night there. At the time, many of New York’s historic cast iron buildings were abandoned and facing demolition.

In Los Angeles, Ed Ruscha photographed “Every Building on the Sunset Strip,” printing them in a continuous line in an elaborate fold-out book. Most buildings were underused, owned by shell corporations waiting for a rise in real estate prices. A similar real estate survey was conducted by artist Hans Haacke in New York.

“Conceptual art is a practice that uses systems and abstractions of data to make art that is not emotive and experiential,” said the third co-curator, Greg Foster Rice of Columbia College, Chicago. “We were trying to say is: That’s part of this period, and really linked to the city. Very few exhibitions tie conceptual art to systems of urbanism.”

Artists contributed to a shift in urban planning. City designers, who had relied largely on aerial photography and street grid maps to make development decisions, started commissioning artists to take pictures of how residents live in the city, reacting to its infrastructure and using open spaces.

In 1969 the New York City Planning Commission published a six-volume plan for the city, one for each borough and an overview. They were distributed for public consumption at every library in New York. The books were illustrated by images of the city and its residents, taken by local artists.

“Instead of just having diagrams and social statistics and maps and maps and more maps, they had street-level views – of kids playing in parks, of people at Coney Island,” said Bussard. “It’s a wonderful sense of what it is to live in New York City.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.