Philly’s restaurant scene is poised for a big resurgence. But there are winners and losers

Philadelphia’s restaurant scene is rebounding after nearly two grueling years of pandemic uncertainty.

Listen 1:54

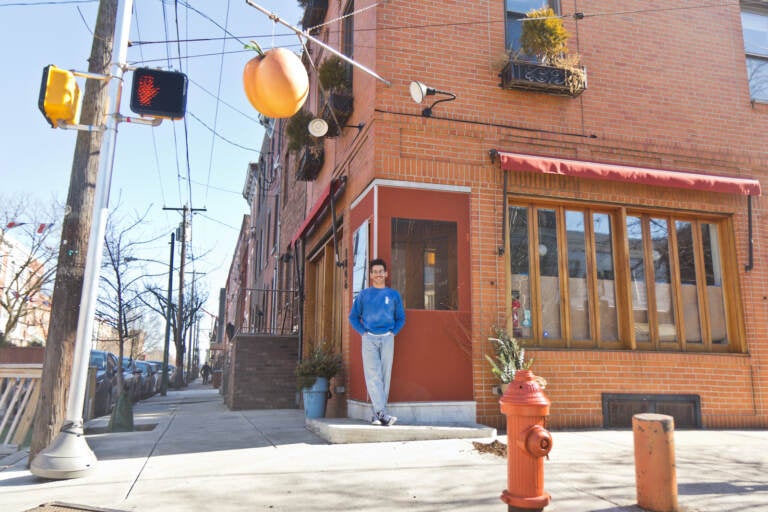

Owner Alex Tewfik outside his new restaurant in South Philadelphia’s Passyunk Square at 11th and Tasker streets. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

On Passyunk Avenue, a freshly hung sign in the shape of a giant apricot swings in front of a corner bistro. On the Delaware waterfront, circular saws whir and hammers clang as the largest dining establishment in Philadelphia takes shape.

Philadelphia’s restaurant scene is rebounding after nearly two grueling years of pandemic uncertainty.

Alex Tewfik, the former food editor at Philadelphia Magazine, said the “vibrant and exciting” energy of the food scene right now finally convinced him to chase a long-held dream of starting his own restaurant.

“All of a sudden all these young chefs, all these new people wanted to do something,” he said, of the pandemic trend of people quitting, or losing, their old jobs and turning to something they are more passionate about. “I got caught up in it,” he continued. After months of preparation and recruiting workers in a tight labor market, Tewfik’s new restaurant Mish Mish, which is Arabic for “apricot,” opens this week.

This moment is far from where many predicted restaurants would be after a global pandemic that has hit the hospitality industry harder than any other.

At the outset of the pandemic, worst-case scenarios envisioned the number of restaurants dropping by 30% in one year, according to the National Restaurant Association. As of 2021, that number wound up being more like about 14% nationwide, according to the association.

Locally, many closures appear to have mostly been offset by new business. While there have been high-profile losses, the total number of food establishments, 12,621, has remained roughly level with the pre-pandemic times, according to the numbers provided by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, which licenses them.

That number includes restaurants, corner stores, and grocery stores. Each business of this type has to have its plan reviewed by the Office of Food Protection, and so within that top-level number, there has been churn.

“For example, there has been a rise in incubators and more mobile food establishments. Anecdotally, we feel this could be due to the influx of pandemic relief funding,” said PDPH communications director James Garrow. He said the city was unable to break out how many of each type of food business there is at this time.

Several factors contributed to stabilizing an industry that even in the best of times has significant turnover. Everything from to-go cocktails, to government stimulus aimed at hospitality businesses, to neighbors supporting takeout and the expansion of outdoor dining have helped get restaurants through, said Ben Fileccia, senior director of operations with the Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association.

Last fall, some businesses exceeded their pre-pandemic levels. “A lot of the numbers that we saw from September were higher than 2019 numbers,” said Fileccia.

However there have been winners and losers. Corner delis and other types of restaurants that rely on office workers have suffered, he said. Foot traffic from workers who live outside Philadelphia’s central core has remained mostly flat, according to regular analyses by Center City District. On the flipside, foot traffic for tourism for events and retail has nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels.

“The high end restaurants with the reputations … those places attract tourists from around the world, they’re going to be fine,” said Jeff Hornstein, executive director of the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. “The places that have gotten killed are the small mom and pops” that do not have a customer base in their neighborhood, he echoed.

Job growth across food service has also picked up, according to an analysis of federal data by the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia. In the last quarter of 2021, food services and drinking places added more jobs than any other sector in the Philadelphia region, returning “almost back” to where it was pre-pandemic, said Hornstein.

That was before the most recent COVID-19 wave. A January survey from the Pennsylvania Restaurant & Lodging Association found that 93% of local restaurants saw a drop in customer demand for indoor dining during that time.

Even as business picks up, many restaurants are not out of the woods yet.

“We’re going to have to consider the next three years as part of the pandemic when we talk about restaurant closures,” said Fileccia, because it will take some places years to earn back what was lost. Mayor Kenney recently joined 24 other mayors in urging Congress to put more money into small business support, such as the Restaurant Revitalization Fund, Axios Philadelphia reported.

As cases started dropping again, business has improved week by week, said Avram Hornik, owner of FCM Hospitality, the company behind venues such as the South Philly dance club, The Dolphin, and riverfront restaurant Morgan’s Pier. But he is no stranger to churn. Lost Bread, an artisan bakery on Walnut Street that FCM opened with baker Alex Bois, closed within the space of one pandemic year.

In April, Hornik plans to open Liberty Point, billed as the largest restaurant in Philadelphia, on the premises of the Seaport Museum. The project was slated to open in Spring 2021, but was held up by lack of labor, and supply chain issues, Hornik said. This year, both of those impediments have improved, and the outlook is better. But he acknowledges that’s not the case for everyone.

“It’s a shuffling of what businesses were winners and what businesses were losers,” said Hornik. “We were lucky, we do a lot of outdoor stuff.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)