In Philly’s black community, charting a way beyond decades of pain toward mental health

Nearly 50 people gathered at the West Philly Library on 52nd Street to talk about mental health in the black community.

Community discussion on trauma, PTSD and access to mental health services at the Blackwell Regional Library in West Philadelphia, on Wednesday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

Wednesday night was warm and springlike, but nearly 50 people opted to stay inside and gather at the West Philly Library on 52nd Street to talk about mental health in the black community.

The topics were big: long wait lists for mental health care, intergenerational trauma, stigma, and suicide.

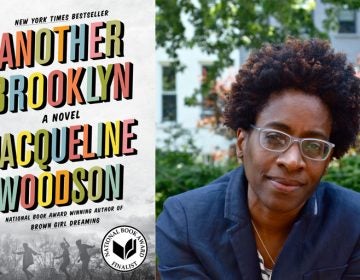

The event was part of One Book, One Philadelphia, a citywide program to promotes literacy and community dialogue centered on a common book. This year, the program is focusing on “Another Brooklyn,” a novel by Jacqueline Woodson about a young black woman named August who returns home to Bushwick for her father’s funeral and remembers her 1970s childhood there. As young girls coming of age, August and her friends cope with death, poverty, violence and sexual assault.

Glen Ellis, a panelist, spoke of how members of the black community have long coped with widespread trauma. He grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and went to school with the four young girls who were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963.

“I had to go to school the next day,” Ellis said.

Unhealed trauma persists today, said panelist Shawn Frogg Banks, a mentor and activist.

“I saw my first body at the age of 7,” he said, although he never talked about it until taking time to work on his mental health as an adult.

“Inner city kids hear gunshots every day,” he said, but resources are scarce.

Therapist Shesheena Bray, who attended the talk, said she left the conversation feeling energized and heartened to hear people name their experiences as traumatic, a word once reserved mostly for war veterans.

It’s a new starting place that allows people to ask different questions, Bray said.

“So we’re understanding that this is a very, very real part of our day-to-day lived experience,” she said. “How do we then counteract, how do we control this, how do we resolve the trauma?”

Panelist and therapist Jaynay Johnson said there’s still a long way to go. There aren’t enough therapists of color, or even therapists who can provide culturally competent care. And most psychological theories weren’t written to include experiences that vary from white, middle-class, and majority male perspectives. But the event felt transformative, she said.

“I think seeing these large numbers just made me feel hopeful that we are really moving toward a healing place,” she said, referring to the evening’s strong turnout.

Panelists and audience members discussed possible solutions. What’s clear, said Johnson, is that there aren’t enough therapists of color.

“There aren’t enough culturally competent clinicians, and there just aren’t enough clinicians of color to spread out in the urban areas as much as we would want them to,” she said.

Panelists also suggested volunteering time in schools where a student has died and actively checking in on people who seemed to need help.

Farida Boyer, a marriage and family therapist who grew up in the 52nd Street Corridor, said she was surprised and delighted by the large turnout. She wondered whether such an event would have attracted so many people when she was growing up in the neighborhood.

“I doubt it,” she said. “I went to school not far from here. We didn’t really talk about mental health.”

Back then, she recalls a heavy stigma — a stigma that still hasn’t dissipated. As a therapist in private practice, Boyer said she’s doing her part to unpack the stories people have about asking for help. She addresses those feelings right away, then, she says, “we can move forward.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.