Philly schools present new, sunnier budget projections

For the first time since Superintendent William Hite took over, his staff presented a long-term budget with no planned deficits.

Philadelphia School District headquarters at Broad and Spring Garden streets. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

For the first time since Superintendent William Hite took over the School District of Philadelphia more than five years ago, his staff presented a long-term budget with no planned deficits.

Thanks to a proposed injection of cash from City Hall, Chief Financial Officer Uri Monson’s annual lump sum budget presentation, delivered Thursday, projected five consecutive years of positive fund balances.

“The School District of Philadelphia is the strongest academic and financial position it has been since I became Superintendent,” said Hite Thursday.

Crucially, the district’s new projections account for money budgeted by Mayor Jim Kenney, who is proposing tax hikes that would help boost district revenue by nearly $1 billion over the next five years. If Kenney’s proposal earns City Council approval, the district would enjoy rare financial stability.

But that’s a big if.

Kenney’s initial plan called for a 6 percent increase to real-estate taxes, and several City Council members seem reticent to support the proposal after approving four recent tax hikes under Mayor Michael Nutter.

Also on Thursday, city officials revised the proposed hike downward to 4.1 percent. An unexpected increase in property values allowed Kenney to scale back his ask, officials said, and still generate about the same amount of revenue. The new plan will produce $966 million over the next five years for Philly schools instead of the estimated $980 million Kenney’s first plan was supposed to yield. Monson said Thursday Kenney’s revision likely won’t shift the outlook of the district’s five-year plan.

Monson believes the latest five-year budget plan, if enacted, will help the district stabilize and build on recent academic gains.

“You can’t just do one-time investments in education,” he said. “Education is a multi-year process. We need to be able to put investments in and have them be recurring.”

During its annual budget presentation — which always precedes the finalization of city and state revenue plans — district officials make their calculations based on whatever chief executives propose. If President Donald Trump, Gov. Tom Wolf, or Mayor Jim Kenney propose new dollars for education spending or spending cuts, the district’s budget incorporates those proposals in its projections.

A lot can change, though, between when an executive proposes a budget and when a legislature passes it. This budget season, the district’s fiscal fate may hang in the balance.

The last time district officials released five-year projections, they estimated Philadelphia’s school system would enter the red by the end of fiscal 2019. Without new money, the district figured it would end fiscal year 2019 with a negative balance of $22.4 million.

Here are those estimates:

| Fiscal year | Projected fund balance |

| 2018 | $85.6 million |

| 2019 | -$22.4 million |

| 2020 | -$218.1 million |

| 2021 | -$449.7 million |

| 2022 | -$701.6 million |

It’s unclear just how big the deficit would have grown by fiscal year 2023, but the trend line suggests, and district official confirm, the number would have been between $900 million and $1 billion.

Kenney’s proposal changes that outlook entirely.

Here is the five-year budget projection Monson unveiled Thursday:

| Fiscal Year | Projected fund balance |

| 2019 | $179.0 million |

| 2020 | $160.0 million |

| 2021 | $126.5 million |

| 2022 | $88.3 million |

| 2023 | $61.3 million |

Notably, those fund balances would start shrinking by fiscal year 2021, even with a big boost from city coffers and taxpayers. In fact by fiscal year 2020, the district would again have an operating deficit that would continue to grow over the remainder of the five-year period.

The root cause of this will be familiar to anyone who has followed district finances in recent years: charter and pension payments.

The district must pay for each Philadelphia child in a charter school, and the more the district spends on its own students the more it must pass along in per-pupil charter payments. That fact combined with the growing presence of charters means the district will devote more and more money to charters over the next five years. District officials believe they’ll be spending $1.26 billion on charters by fiscal year 2023, up from $903 million this school year. And while rising charter payments reflect teaching fewer students in traditional schools, district officials say their actual expenses don’t decline enough to cover the lost funds.

The district’s other major rising cost is pension payments, set by the state each December. Because the state’s pension system was starved of cash in its early years, the state has recently asked districts to pay a larger and larger share of the money due to retired teachers.

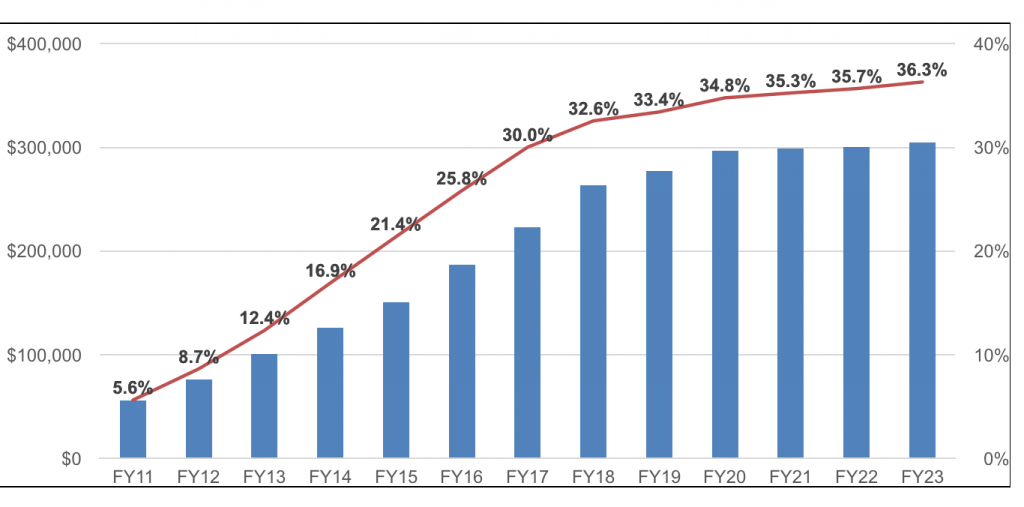

In fiscal year 2011 the payment rate for districts was 5.6 percent. By 2023 it’s scheduled to reach 36.3 percent. The district chart below shows that growth.

Even with a big pile of new money from the city, those growing expenses — both set by state law — would continue to grow.

Short term, though, the district is planning to invest, with plans to expand upon many of its recent initiatives.

Monson outlined what the district would do with the new city money during the upcoming school year. The proposal included:

- Hiring about 60 teachers to eliminate “split” classrooms in 1st or 2nd grades. “Split” classrooms are when students across multiple grades are grouped into the same homeroom.

- Hiring 30 more ESOL teachers for students learning to speak English.

- Adding a handful of itinerant music teachers and creating a $1.5 million fund for schools to buy art and music supplies.

- Extending the district’s efforts to modernize elementary school classrooms with a focus on early literacy.

- Adding 10 new programs for special-education students requiring emotional support, part of a broader effort by the district to serve kids who have traditionally been assigned to specialized private schools.

The district also wants to renovate Ben Franklin High School so that Science Leadership Academy, a lauded magnet school, can move into underused parts of the building.

On the expense side of the ledger, the district does not plan to close any schools this year to reduce costs. The district originally said it would close three school a year to account for declining enrollment, much of it driven by charter expansion. It appears, however, officials won’t follow through on that plan for the upcoming school year.

“I don’t support additional closures,” said Joyce Wilkerson, head of the dissolving School Reform Commission and candidate for the new local school board that will replace it. “I think that we have to maintain enough of an infrastructure that we can have a robust system of public schools.”

If City Council okays mayor’s budget proposal, the district wouldn’t need to close schools to maintain solvency or ward off any other service cuts.

Rounding out the financial news, school officials also announced Thursday they sold $254 million in bonds to finance infrastructure projects. Thanks to the district’s improving financial health, Monson said, the district will pay a significantly lower interest rate on those loan than it did 18 months ago, the last time it sold bonds.

With the lowered interest rates, Monson calculated, the district will save about $18 million over the 25-year life of the bonds.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.