Philly school district finance chief: Forecast looks shaky after election

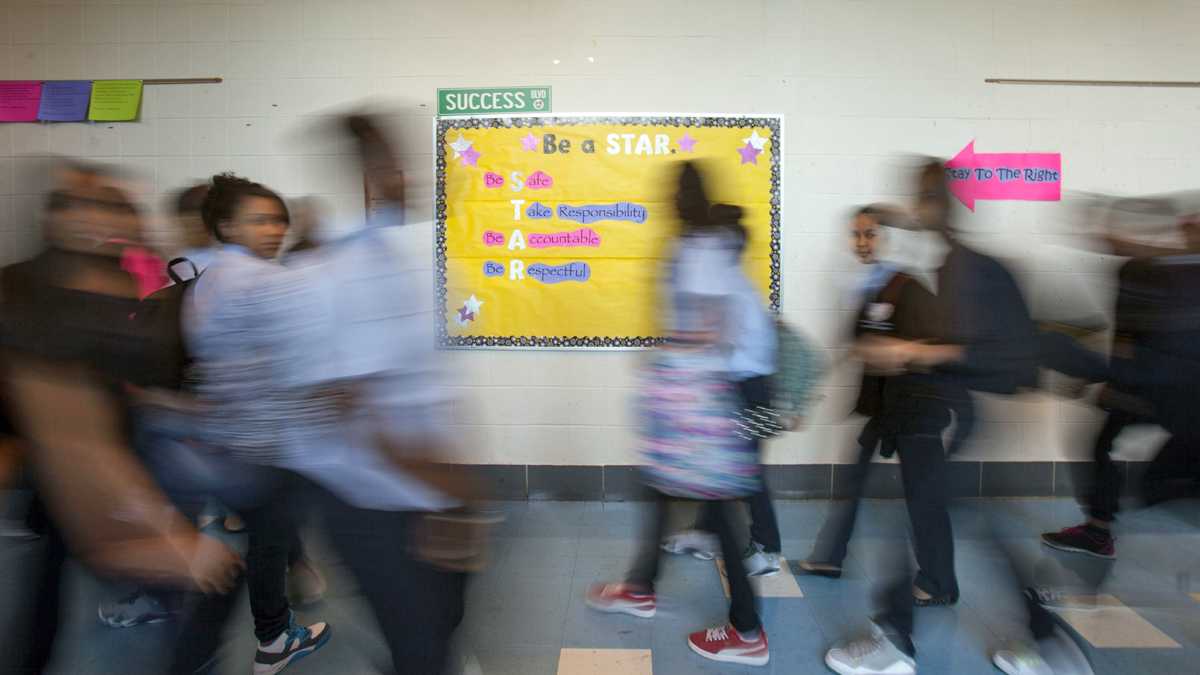

Middle school students change classes in Philadelphia. (Jessica Kourkounis/WHYY)

When Uri Monson, chief financial officer for the School District of Philadelphia, bolts out of bed at 2 a.m. and can’t get back to sleep, he isn’t thinking about monsters in his closet.

He’s thinking about uncertainty.

Uncertainty is the bogeyman for fiscal planning types. And the way Monson sees it, unknowns are abundant these days — many of them stemming from the events of last month.

On Election Day, Republicans made big gains in Harrisburg and locked up a veto-proof majority in Pennsylvania’s Senate. That could make for a bitter showdown with Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf over the upcoming state budget. At the federal level, Donald Trump swept into the White House accompanied by vague suggestions that his administration could expand school choice, slash federal funding for low-income students — or both.

Also in the past month, Pennsylvania’s nonpartisan Independent Fiscal Office projected a $1.7 billion deficit for the next fiscal year, and the board that runs the state’s teacher pension system voted through a higher-than-expected increase in the amount each school district must contribute.

Taken altogether, Monson sees a financial forecast that looks bleaker today than it did when the school year began. He’s already fretting about how the perpetually cash-strapped district might have to adjust if the state or federal government pulls money.

“Those are my early-morning-hours thoughts, running through scenarios, how you account for those funds, what you can do to work around it, and how you can prepare,” Monson said.

It’s impossible to know how the latest election and the state’s budget hole could impact Philadelphia’s public schools. But for Monson that’s precisely the problem.

“You need to have stable finances so you can make stable investments in kids,” he said. “It’s really hard to put investments in and pull them back out again.”

Federal changes loom

Federal policy may represent the biggest unknown.

During his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump floated the idea of a $20 billion school voucher program, and his pick for Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, is a longtime champion of school choice. That alone could prove problematic for the district’s bottom line if it leads to student migration and a corresponding enrollment decline.

Trump also said the money for his proposed voucher program would come from existing federal funds, and some have speculated that the money could come out of Title I and other programs through which the U.S. Department of Education directs money to low-income schools. There are logistical challenges of such an approach given the nature of those disbursements.

If there were, however, a dramatic reduction in federal aid, poor school districts such as Philadelphia would be the hardest hit. In fiscal year 2017, the district received $175 million from the federal government through the Title I program, which steers extra resources to districts that serve large proportions of low-income students. That money is enough to support the equivalent of 1,946 full-time positions. Most positions funded through federal grants are union represented, said Monson, which means the district would have to draw from its general fund to retain those staff members if the federal government decided not to pick up the bill.

Altogether, federal grants make up $316 million of the district’s current budget. That’s significantly less than what Philadelphia’s public schools receive from the city and state governments, but still a significant chunk of its nearly $3 billion budget.

So is the district justified in its worry over the fate of federal dollars? Perhaps, said Michael Casserly, executive director of Council of the Great City Schools, an organization that represents urban school districts.

“It’s never too early to be worried,” said Casserly. “On the other hand, the administration hasn’t been sworn in yet. They haven’t laid out any proposals. They haven’t said a lot about education spending.”

Besides, Casserly noted, it’s Congress that controls appropriations. Philadelphia may need to pay special attention to the political winds because of its often-precarious financial position, but panic isn’t in order, he said.

State funding fears add to worries

The state’s financial situation may prove more alarming, at least in the immediate future.

“I would say [school districts] are absolutely, extremely concerned,” said Jay Himes, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials.

“The news out of Harrisburg “hasn’t been very good” this year, said Himes. As a result, districts are feeling skittish. That’s partly due to the projected deficit and partly due to lingering doubts created by a recent budget impasse that lasted nine months and left many school districts gasping for funds.

“I think people are concerned that all of the crumbs seem to be leading to a conclusion that it might be as bad this year,” said Himes.

As a result, said Jim Buckheit, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators, school districts are headed into the preliminary budgeting process for the next school year with “very low expectations in terms of state funding.”

Most districts, Buckheit predicted, will raise local taxes to compensate for uncertainty in Harrisburg. Philadelphia, however, doesn’t have that fallback.

The school district in Pennsylvania’s largest city can’t levy its own taxes. It is thus at the monetary mercy of Washington, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia’s City Council.

“For us, we can lose on one side, and then we have to go back to our funders who control our funding and say, can you make this up,” said Monson.

Contract stalemate hangs in balance

Union There is a clear political dimension to Monson’s unease.

For years, the district has haggled with its teachers union over the terms of a new collective bargaining agreement. Meanwhile, teachers have gone nearly five years without raises and more than three years without a contract.

As reported recently by the Philadelphia Inquirer, the district has put an offer on the table worth $100 million. Monson said the district hasn’t withdrawn that offer — which was calculated and proposed before the November election — but he feels queasier about the deal than he did earlier this year.

“It’s another half hour less sleep a night for me thinking about this stuff,” he said. “It means that our risk factors have gone up significantly.”

That argument doesn’t sway Jerry Jordan, head of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

“It’s not the first time we’ve had elections in this country,” said Jordan. “One could have made that same point in 2000 when George W. Bush became president. And we can make that same argument or a similar argument every time there’s a new governor or a new legislature in Harrisburg.”

Jordan believes the district should think harder about how it allocates the money it already has. He blames the district for approving new charter schools, which drain money from district coffers. The union leader also balked at the suggestion by district officials that they’re hemmed in by the district’s inability to raise taxes. If that’s the case, Jordan, said, the district should press harder for taxing authority.

Monson said he wants a new contract and has worked on the issue more than any other since becoming CFO in February. Inking a new deal would eliminate some of the uncertainty he dreads so much.

“It’s the unknowns you want to take care of,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.