Philly families live with crushing heartbreak as COVID-19, gun violence crises collide

The number of murders has risen to record levels in Philly, especially in neighborhoods also hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Listen 4:31

Kimberly Kamara holds a children’s book she wrote to help explain to her grandson how his father’s life ended tragically. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The doorbell startled Andre Davis.

He had just finished ironing his work clothes and was moments away from slipping into bed for the evening.

That wouldn’t happen for hours now.

Two police officers stood on the other side of his front door. They needed to talk to him about Robert.

“I thought maybe he had gotten in trouble,” Davis said.

Inside their Olney rowhome, officers showed Davis and his wife a cell phone photo of their 21-year-old son, Robert Wood.

The officers told them there had been a fight. Robert was shot. He didn’t make it.

“My wife was hysterical. My daughter was hysterical. And we just started making phone calls,” Davis said.

It was 2 a.m. before Davis turned off the lights and tried to sleep.

He couldn’t.

‘I’ve never seen this level of violence’

Robert Wood was murdered during what remains an exceedingly violent period in Philadelphia. The city’s murder rate so far in 2020 is the highest it has been since 2007.

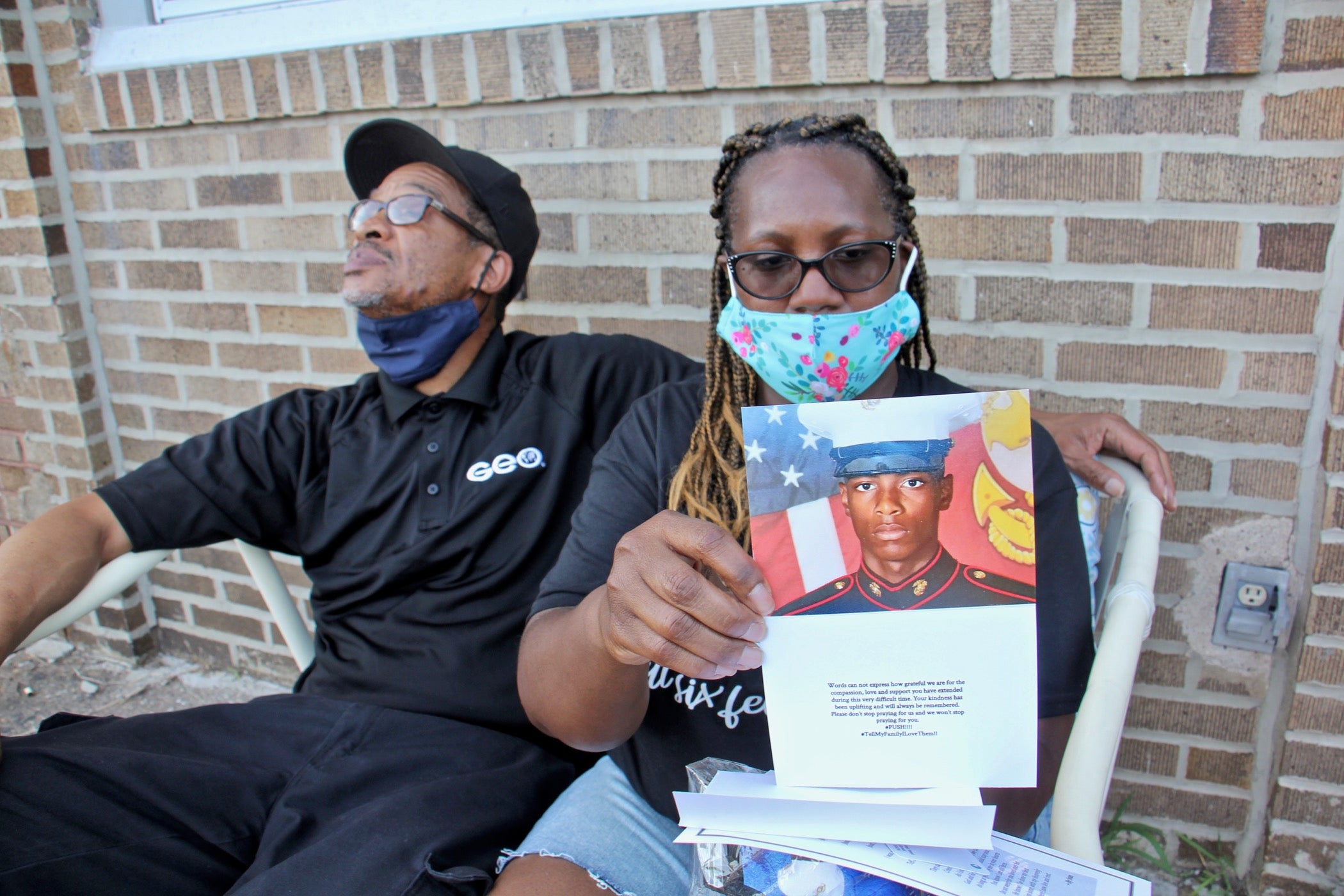

Wood was a Marine pursuing a criminal justice degree. He dreamt of being in law enforcement but was shot and killed on the street before he got the chance.

Experts predicted most crime would decrease during the coronavirus pandemic, but the number of shooting victims and homicides in Philadelphia has surged since early March — despite a stay-at-home order that lasted more than two months and ongoing calls from public health officials to maintain social distancing.

“As long as I’ve been working in the streets, I’ve never seen this level of violence — back-to-back-to-back-to back — here in the city of Philadelphia,” said Colwin Williams, a longtime anti-violence activist.

As of July 12, the last date for which statistics were available, police have recorded 946 people shot so far in 2020 — a 31% increase compared to the same time last year.

To date, the city has recorded 224 people murdered — a 26% increase compared to the same period last year.

In that time, residents have endured some exceptionally violent days. Most recently, 23 people were shot across the city on July 5 — the highest single-day total in nearly a decade. Six of them died, including 6-year-old Fakeem Hayes, who was accidentally shot in the chest by a younger child in the Holmesburg section of Northeast Philadelphia.

Amplifying the anguish, new research shows many of the neighborhoods hit hardest by gun violence during the pandemic have recorded high rates of coronavirus infections as well. That includes slices of North Philadelphia, as well as a section of West Philadelphia sandwiched between University City and Delaware County.

7/

Through #geospatial mapping, we were able to find a significant relationship of shooting events occurring with a higher incidence in those #Philadelphia neighborhoods most affected by #COVID19 infection. pic.twitter.com/0SDRrlETN1— Zaf #WearADamnMask Qasim 🇵🇰🇬🇧🇺🇸 (@ResusOne) July 6, 2020

“As the COVID numbers increased, so did the penetrating trauma cases — in particular, shootings,” said Dr. Zaffer Qasim, assistant professor of emergency medicine and critical care at the University of Pennsylvania, which led the study. “Penetrating trauma cases” involve stabbings or shootings.

Between March 9 and April 19, 187 people were shot in Philadelphia.

During that six-week span, nearly 20 of them were struck in the three zip codes of West Philadelphia that include the Overbrook Park and Mill Creek sections of the city. Those zip codes, where up to a third of residents live below the federal poverty line and roughly 90% of the population is Black, were also among the areas of the city with the highest rates of COVID-19.

By comparison, one person was shot in three zip codes of northwest Philadelphia that contain Roxborough, Manayunk and East Falls. The middle-class, majority-white neighborhoods were among the areas of the city with the lowest rates of COVID-19.

The correlation between the virus and violence is not surprising, given Philadelphia has known for years that residents of different ZIP codes have widely different health outcomes.

A city report released last year showed that residents in low-income, higher-crime ZIP codes have shorter life expectancies and higher rates of diabetes, cancer and asthma — three health conditions that make people more vulnerable to the coronavirus — than residents of wealthier ones with lower crime rates. Those ailments are also more prevalent among Black residents, who have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic in Philadelphia and across the U.S.

“As with many things that COVID-19 has done, it’s kind of taken a scab off the wound that was already there in some ways,” Qasim said.

‘A piece of your heart someone has taken away’

Robert Wood was killed on June 7 in a section of North Philadelphia that bucks the correlation Qasim’s research found. While there were nearly a dozen shooting victims in the six weeks researchers studied, the area had one of the lowest rates of COVID-19 cases in the city.

Shortly after getting off the bus, police said Wood was robbed by at least one man with a gun and was shot in the back and the chest on the 2300 block of West Berks Street.

His parents still don’t know where he was going that evening.

“What we do know is that he left home about 6:15 p.m. that day, and apparently he didn’t even get to his destination. He was walking to his destination and they gunned him down,” said his mother, Tailynn Davis.

Wood’s father believes he was targeted.

“It sounds like a set-up to me,” Andre Davis said. “It’s hard for me to swallow that it was random.”

Police later arrested 23-year-old Devante Bennett, who was shot in the arm during the robbery, in connection to the killing. He’s charged with murder, robbery, conspiracy and weapons offenses. It’s unclear if Bennett is accused of shooting Wood, the second son the Davis family has lost to gun violence in three years.

Robert Wood’s older brother, Andre Davis Jr., was killed in West Philadelphia while trying to break up a fight involving a friend, according to his father. He was 33.

In the weeks since their younger son’s murder, Tailynn and Andre have felt overwhelmed at times.

“I can’t square it,” said Andre, who is also heartbroken that he won’t see his son get married or become a father.

About a year before he was murdered, Wood texted his parents a photo from a military ball he attended in Oklahoma, where he was training. When he came home, he and his father had a one-on-one conversation about his date, the “amazing” young woman in the red and black dress, and about love in general.

The two men had never talked that way.

“I was waiting until he got to that point. I couldn’t wait,” Andre said.

The couple buried their son in his dress blues just over a week after his murder. Though he had only recently joined the Marines as a reservist, Wood was given a military funeral.

Marines draped an American flag over the casket and honored Wood with a 21-gun salute. Dozens gathered in face masks at the gravesite after circulating in and out of the viewing to diminish the health risks.

Tailynn said life during the pandemic was already stressful. She works in the medical records department of a doctor’s office. Andre is a corrections officer in Delaware County. Until everyone in the jail was tested, Tailynn spent weeks worrying about her husband becoming infected with COVID-19.

“My husband would come home every day. I’d start checking his head saying, ‘Let me check your temperature.’ I was just getting real paranoid,” she said, especially in mid-April after dozens of staffers and men incarcerated at George W. Hill Correctional Facility tested positive for the virus.

Tailynn said the stress of the pandemic has made her son’s death more difficult to fathom.

“You got going to work, you have the death, you have this pandemic, you have trying to stay focused,” she said. “But pandemic or no pandemic, it’s literally a piece of your heart that someone has taken away from you that you cannot get back.”

COVID-19 hampering violence prevention efforts

Kimberly Kamara has felt that pain for the last three years, ever since her son was shot and killed outside his girlfriend’s house in Germantown. The 23-year-old was there visiting his newborn son.

“It’s different when it’s your child that has been murdered. It does something to you different. And you either get up fighting or you just fall into a depression,” said Kamara outside her home on Johnson Street.

Kamara has felt both the urge to fight and the tug of depression during the pandemic.

Spending more time at home has given her the chance to finish writing a children’s book designed to help parents talk to their kids about death, particularly after a loved one is lost to gun violence. But being inside more has also made her son’s absence feel more pronounced.

She often finds herself looking out of the front window she used to stand at when her son returned home from a friend’s house.

At times, she’s felt crushed by her son’s murder.

“More than I can count — a lot,” Kamara said.

Watching the city’s ongoing gun violence crisis, as well as two cousins die from COVID-19 has added to her pain.

“Each time you hear a story, you just can’t help but to cry because now you know there is a mother out there crying for their child,” she said.

Despite the uptick in gun violence over the last four months, it’s unclear the extent to which the increase in shootings is related to the public health crisis and the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Researchers and anti-violence activists say poverty, high unemployment and more unstructured time are factors likely fueling some of the violence, but they stop short of drawing a direct correlation between COVID-19 and the city’s violent crime stats over the last few months.

“There’s a significant contribution from COVID-19, but how tight that association is and whether there’s a direct effect of one or the other, that needs a little bit more study,” Qasim said.

The police department isn’t making the distinction either but says there certainly could be a correlation between the two.

“With fewer persons on the street, and mostly law-abiding citizens remaining indoors, offenders and their targets have been more likely to encounter each other without obstruction or impediment,” said department spokesperson Inspector Sekou Kinebrew in an email.

And with fewer people on the street, there is less potential for eye-witnesses, potentially emboldening those responsible for the shootings, he added.

Police also attribute the increase in violence to existing rivalries between gangs and other groups, continued competition over drug turf, and “beefs” between people with “poor conflict-resolution skills.”

In late June, amid protests over police brutality and calls for radical changes to policing, the department released a plan that calls for pairing more crime prevention and community-building efforts with traditional law enforcement. The plan also includes the creation of the Group Violence Initiative, a program that will involve regular discussions between police, community leaders and “gang or group-involved individuals,” many of whom are on probation or parole.

The goal is two-fold: to prevent conflicts from escalating into gun violence, while sending a message that police will not tolerate shootings.

The plan also calls on district police commanders to develop and implement quarterly crime plans that are data- and intelligence-driven, as well as focused on violent crime “hot spots.” Officials hope these plans will make crime-fighting more tailored and nimble.

Williams, the anti-violence activist, said the bloodshed is devastating — and incredibly frustrating — no matter what’s driving it.

Williams is a street supervisor with Cure Violence, a nonprofit that sends outreach workers into police districts with high levels of violence in North and West Philadelphia. Many of the outreach workers have criminal records and personal experience with the nuanced dynamics of the streets. Their goal is to de-escalate conflicts in the community before someone fires a gun.

Cure Violence is credited with reducing shootings by 30% over three years in the North Philadelphia neighborhoods the program targeted between 2011 and 2014, the most recent years for which data is available. They consider their approach to be akin to a public health prevention model of stopping violence before it starts.

But since the pandemic hit the city, Williams and his team of “violence interrupters” haven’t been able to hit the streets to talk to people in person, only by phone, making it difficult to get a full picture of the violence in the neighborhood or why it is happening.

“In March and April, we had more contacts. We were able to engage them,” said Williams. “But as the weather got warm, it seemed like it was harder to reach them. No one’s calling. Everyone is back in the streets in one capacity or the other.”

In the meantime, the number of shootings and murders has continued to mount, even as the daily number of positive COVID-19 cases plateaued, then declined to a point where the city was preparing to resume many daily activities.

COVID-19 case counts in Philly have since leveled off or slightly increased each day, making it unclear when it will be safe enough to resume traditional outreach work.

“We need to get back out there. It’s a necessity,” said Williams. “It’s almost like a fire. When the fire is there, you must go and respond — regardless of the circumstances.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)