Debates have proved a tough test for vice presidents running for president

When VP Harris takes the stage in Philly Tuesday with Donald Trump, she will be the first sitting vice president to debate someone who had actually been president.

Kamala Harris accepts her nomination on the final night of the DNC. (Grace Widyatmadja/NPR)

Since the era of TV debates began in 1960, there have been 17 presidential election cycles and all but three have featured at least one televised faceoff between the nominees of the major parties.

When Vice President Harris takes the stage in Philadelphia Tuesday night on ABC with former President Donald Trump, she will be the first sitting vice president to debate someone who had actually been president.

But there have been six others who were vice president or had a history in that office when they debated on TV as their party’s nominee for the Oval Office. And their record has been mostly one of disappointment, both in the debate itself and in the election that followed.

Three were outshone in the debates and then defeated in the election that followed. All three retired from politics thereafter.

Two held their own in their debates the year they won the nation’s ultimate office, only to stumble in their debates as incumbents four years later and be denied reelection.

And there was the very first vice president who debated on TV as the nominee of his party, Richard Nixon, whose performance in 1960 may have cost him an election and cast a shadow on the era of presidential debates that followed.

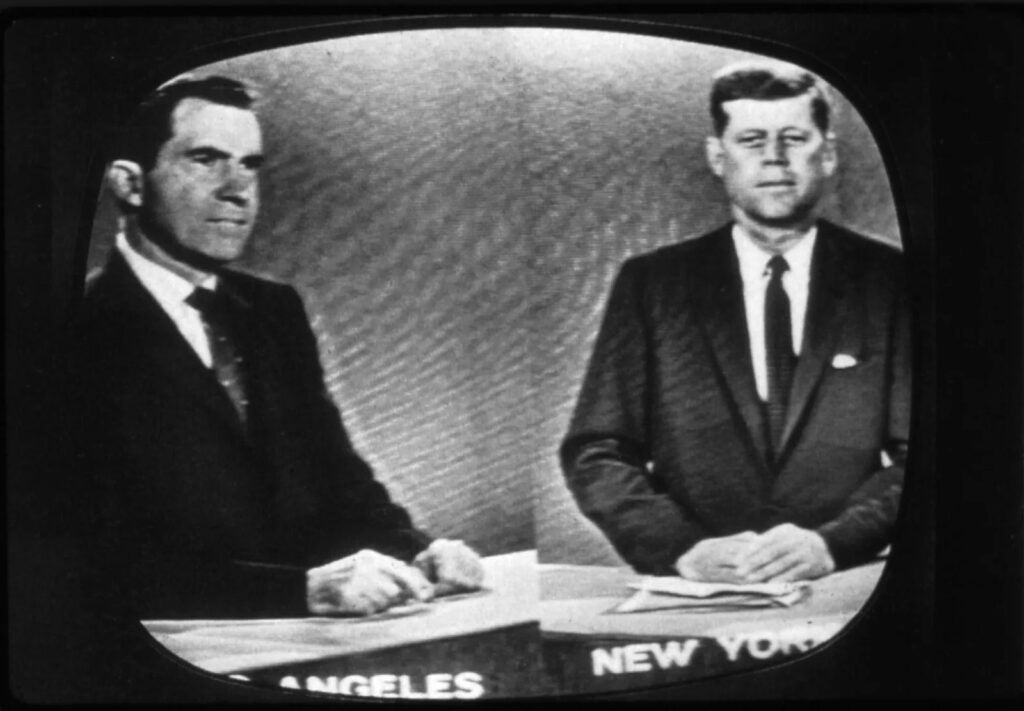

Nixon puts his stamp on the era

For more than 60 years, Richard Nixon’s performance in the first debate ever televised between presidential nominees has been held up as an example of campaign error. Nixon had been ill and was reluctant to use much TV make-up for his paleness and his famous “five o’clock shadow.” The contrast was notable in the era of black-and-white television.

Moreover, Nixon seemed ill at ease, especially in contrast to the supremely confident demeanor of his opponent, the young Democratic senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy. Still introducing himself to much of the nation, Kennedy managed to convey seriousness commensurate with the office he was seeking. And while the debate format did not give him much chance to charm, his soon-to-be legendary charisma had a way of glimmering through.

Some scholars have argued that too much was made of the Nixon-JFK debate and its contrasts, given that much of the nation did not watch and there was little measurable effect on the polls.

But the impression that “Nixon blew it” took on a life of its own.

In 1964, the man who succeeded to the presidency on Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson, saw little reason to risk a debate with his opponent, Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona. There was no debate and LBJ won in a landslide.

Four years later, LBJ was leaving office and Nixon was again the Republican nominee. This time, Nixon was leading in the polls and saw himself with more to lose than gain in a debate. So he did not debate his opponent (sitting Vice President Hubert Humphrey) and won in November.

As an incumbent in 1972, sailing to reelection in a 49-state blowout, Nixon would again demur on the suggestion of debates.

Ford brings the debate back into focus

But much changed after Nixon’s reelection, beginning with his own fortunes. Probes of burglaries and other offenses by his 1972 campaign operatives led him to oversee a White House cover-up of what was known as the Watergate scandal. That in turn led to more investigations and Nixon resigned as Congress was about to impeach him in 1974.

He was succeeded by his vice president, Gerald Ford, whom Nixon had appointed to replace his first vice president, who had resigned due to scandals of his own.

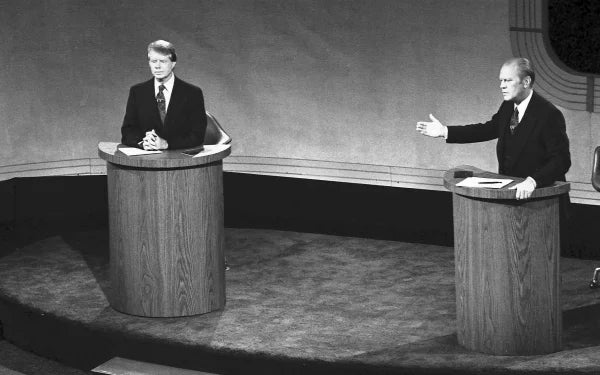

Ford, a longtime Republican member of Congress from Michigan and a party leader, did not have much time to establish himself as vice president before taking over the Oval Office. And he alienated many by issuing a blanket pardon for Nixon. Still, he beat back a challenge to his nomination in 1976 and entered the fall campaign that year with a decent chance to win a term of his own. He wanted to debate the Democratic nominee, former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, to establish his own bona fides and emerge from Nixon’s shadow.

It was the first time the two major party nominees had agreed to a TV showdown in 16 years.

Both candidates were relatively new to the national scene. Carter stressed his executive experience, his roots in the rural South and his commitment to the civil rights movement as well as to his Baptist faith.

But Ford held his own on the debate stage, at least until he offered up a line that would dominate much of the news reporting on TV and in print. When a question arose about Nixon’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union and its effect on Eastern European countries still behind the “Iron Curtain” of communism, Ford said he did not think Poles felt dominated.

Given that Poland had been occupied by Soviet troops and central to the pro-Moscow “Warsaw Pact” for decades after World War II, Ford’s answer was construed by some as naïve. Fairly or not, it weakened his image as the candidate best prepared to represent the U.S. on the world stage.

The debates giveth and taketh away

The next vice president to be nominated for president by either party was Walter Mondale, who had served in that role during the one term Carter won in 1976. In 1980, Mondale had watched Carter march confidently into a debate with his Republican challenger of that year, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan. He had seen how Reagan’s blend of tough talk and avuncular likability upstaged Carter’s own style of personal appeal.

Yet when Mondale won the nomination to challenge Reagan’s reelection in 1984, he was eager to debate the incumbent. He knew he needed something powerful to overcome Reagan’s aura of success and lead in the polls. Some in Reagan’s circle saw little reason to debate the underdog and may have wondered whether, at 73, the nation’s oldest president might be showing some signs of age.

In the first debate that fall, Reagan did seem less than sharp and a bit confused at times, prompting concern in the GOP and giving Democrats hope. But at a second debate, Reagan took a question about age as an issue and made it a deft joke about “my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” He went on to win 49 states.

Reagan’s own vice president, George H.W. Bush, managed to subdue a field of challengers in 1988 to win the nomination to succeed him. He was not seen as a compelling figure onstage and had struggled in debates in other cycles, but he helped himself in his meeting with the Democratic nominee that year, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis.

Having been Reagan’s backup for eight years, Bush was ready to parry attacks on the weak points of the administration’s record and eager to wrap himself in his predecessor’s enduring personal popularity. Dukakis stressed his cool “competence” and at times sounded technocratic.

Bush may not have been especially impressive, but he was the more personable of the two.

That kind of contest was far harder for Bush to win four years later, when he found himself onstage against a young Bill Clinton, then the savvy and smooth-talking governor of Arkansas, who was 22 years his junior — the widest age gap between the major party nominees since before the Civil War.

Bush also found himself debating H. Ross Perot, a billionaire running as an independent who had soared in opinion polls after spending some of his fortune on TV ads attacking both parties and Bush in particular.

As the incumbent president, Bush was the centerpiece of the debates in 1992 but was not their focal point. He seemed at times to recede, caught between the two more dynamic personalities of his opponents. He seemed to underline this when caught glancing at his wristwatch and betraying a sense of impatience.

When Clinton won the presidency that year, his running mate was Tennessee Sen. Al Gore, who had little trouble winning the nomination to succeed Clinton in 2000. The economy was humming along, personal computers were transforming work and school and Gore had worked hard to separate himself from Clinton’s impeachment over an affair with a young White House intern.

Ironically, his opponent was another George Bush, the namesake son of the former president and himself a reelected governor of Texas. Gore and Bush held three televised debates that fall, and while neither candidate was regarded as having dominated, Gore’s efforts to belittle Bush as a lightweight may have backfired. His habit of rolling his eyes in mock disbelief struck some as condescending. And while the younger Bush was not a scintillating debater, he had the quality campaign consultants call “relatability.”

The importance of the debates in 2000 is itself debatable, as was the importance of these events in previous cycles. In the end, it probably mattered more that a third-party bid by consumer activist Ralph Nader split some of the Democratic vote in key states — especially Florida. That was the year that state made the difference in the Electoral College after giving the Republican a popular vote edge of just 537 votes statewide.

The return of the two-edged sword

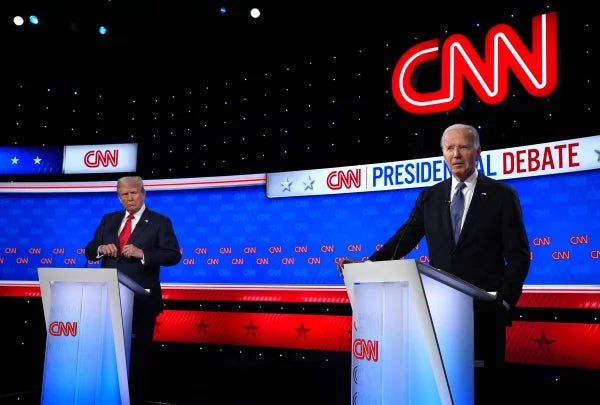

The most recent one-term president in the TV debate era might also be said to have both benefited and suffered from debating before the nation. The current resident of the White House, President Biden, probably helped himself in some measure by withstanding the fury of his opponent in the 2020 debates.

That opponent was, of course, Donald Trump, who was still a formidable incumbent that fall after surviving an impeachment vote in the Senate and a bout with COVID, both in his reelection year. In the end, his efforts to downplay the COVID threat and blame others for its economic impact were the main contributors to his defeat that fall. But he seemed resolved to blow Biden off the stage with his aggressive performance, especially in the first of those two meetings that fall.

Biden had in fact not been seen as a world-class debater in his several bids for the presidency, particularly onstage as a rival to eventual nominee Barack Obama in 2008. But he had been a six-term senator and still retained much of the positive impression he had made as Obama’s vice president for the eight years that followed. He did not run to succeed his boss in 2016. His son Beau was battling cancer, and Obama’s secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, had already taken the inside lane to that year’s nomination.

But in 2020, in his late 70s, Biden ran for president and this time found the formula. He survived a weak start in the primaries and won the nomination going away — thanks largely to strong support among African American voters.

That fall, Biden had two televised debates with the incumbent Trump. The first, in September, was notable chiefly for Trump’s highly aggressive style, interrupting and commenting audibly when it was Biden’s turn to speak and generally ignoring moderators’ attempt to moderate.

The second Trump-Biden debate, in October, proved less raucous. But Trump once again sacrificed the air of incumbency favored in the past by sitting presidents and remained relentlessly on offense against Biden.

This fall, Trump is the first former president to be nominated again after being defeated since Grover Cleveland in 1892.

And he will be facing the current vice president who was elected alongside Biden four years ago. Harris and Trump have never met face to face. But it seems a good bet that Harris will be reviewing the videotape of Trump’s performance in those debates four years ago.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.