The Philadelphia region is getting hit with norovirus. Here’s how to avoid this bug

One expert says the rate of norovirus infections has increased substantially this year compared to years past.

Listen 1:12

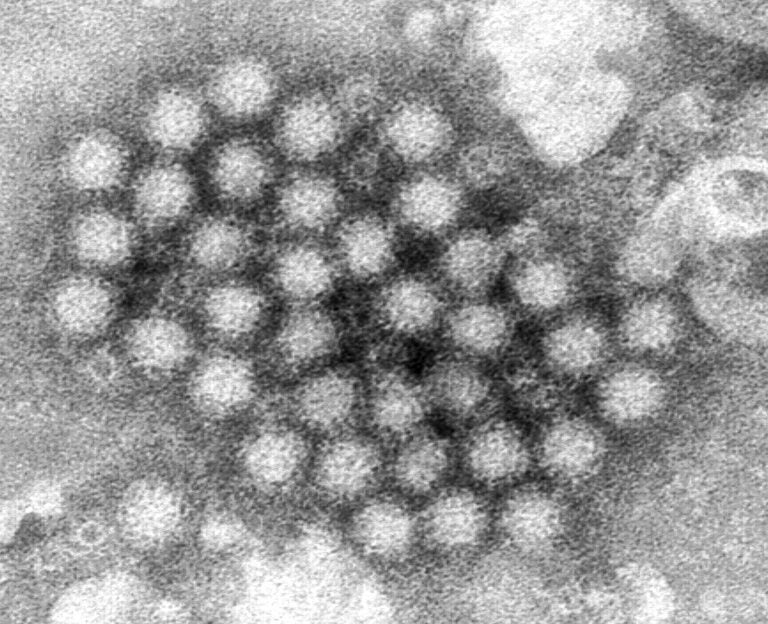

This electron microscope image provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows a cluster of norovirus virions. (Charles D. Humphrey/CDC via AP)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Almost 20 years later, Carlene Muto still remembers vividly her first personal encounter with norovirus — a stomach bug that, she says, once you experience, “you will never forget.”

“It still is permanently burned in my memory as the most awful thing,” said Muto, a physician who serves as the medical director of Infection Prevention and Control for Temple Health. “I was with my sister, and we were shopping for her bridal dress and, oh God — we barely made it home. It was horrible.”

Norovirus usually isn’t deadly — but it is miserable, usually causing one to three days of near-constant vomiting and diarrhea. Worse, it’s incredibly contagious, and currently in the midst of a major surge, both locally and nationwide.

“We’ve seen an incredible increase,” Muto said. “I think we’re double any number of outbreaks in any of the previous years.”

And that means it’s even more important to do everything you can to protect yourself.

How and where norovirus spreads

Norovirus can be contracted year-round, but it’s especially prevalent in the fall and winter, when more people are spending their time inside, in close quarters.

It’s the leading cause of foodborne illness in the U.S., and is frequently spread in food service settings via infected workers. The CDC says ready-to-eat foods, like raw fruits and vegetables, as well as shellfish like oysters, are especially common vectors.

It can also be contracted directly from someone who’s infected — especially in settings where bodily fluids are rampant, like daycares or hospitals.

“There is a huge ick factor here, which is to say that to get norovirus, you have to have a couple of particles from somebody else’s stool [or vomit] go into your mouth,” said Lori Handy, an infectious disease physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “Now, that might sound impossible, but what really happens is one person might vomit, and those particles then are all over the room, wherever they vomited on the floor, they’re on the mom’s robe when they caught the vomit of their four-year-old, and then you make one little movement towards your face and your mouth, and you contaminate yourself.”

Part of what makes norovirus so contagious is the fact that it takes very few virus particles to infect someone. It can also survive for days or even weeks on surfaces, and is resistant to many common disinfectants, including hand sanitizer.

“It’s a very, very hardy virus,” Handy said. “You need to use a disinfectant that works against it, ideally bleach, though there are others, and really clean up every single one of those little particles so that a next person can’t come along and pick that up and then touch their face and have the cycle continue.”

Another factor contributing to its spread is how long it remains contagious.

“The crazy thing is, you can give it to people two weeks after you’re well,” Muto said, adding that although the number of virus particles will decrease along with the symptoms, germs can still spread through insufficient handwashing. “It’s so communicable, meaning it’s spread so easily in families or amongst your friends, that they’ll all get it too and hate you for it.”

How to protect yourself

The No. 1 recommendation from experts is to wash your hands often and well.

“Anytime you come into contact with vomit or stool, you have to do really excellent hand hygiene,” Handy said, “and that is 20 to 30 seconds of soap and water, cleaning the front of your hands, the back of your hands, under your nails, anything that got contaminated, and eliminating the virus particles by almost friction and getting them to wash away.”

It’s harder to avoid for those living with someone who’s infected, but precautions can still be taken — for instance, parents might consider masking if their child is actively vomiting. Infected people should also stay out of the kitchen. Any utensils, dishes or surfaces they come in contact with should be disinfected with bleach or another cleanser that’s effective against the virus.

Handy also recommends avoiding shared food, both in the home and beyond.

“So think of the shared bowl of popcorn in the office break room,” Handy said. “One person who has some norovirus particles on their hands puts their hand in the bowl of popcorn. The next person who comes along now picks up a handful of norovirus, and so while you’re sharing food, you can spread it through very many people.”

The solution: serving spoons, handwashing or simply avoiding any foods that are being touched by multiple people.

Muto’s final tip: stay home if you’re sick or have recently been sick.

“First of all, you can’t function — you can’t work in an office or be out working in the environment or something, because literally you really have to use the bathroom too many times,” she said. “And don’t make others sick. Don’t send your kid back too soon.”

Treating norovirus

For the most part, there isn’t much you can do to treat norovirus, beyond keeping hydrated.

Handy advises talking to your child’s pediatrician first, but she usually counsels parents against giving their children antidiarrheal or anti-nausea medications in the early stages of the illness, because vomiting and diarrhea are the body’s way of getting rid of the infection.

“After that very acute period, I do think there’s a role for antidiarrheal agents as your gut is recovering and healing, and then other medicines that can help with vomiting, to get through that recovery period of getting fluids back in,” Handy said. “Antiemetics, we’ll call them anti-nausea medicines, can really help with that.”

Muto says, for healthy adults, it usually isn’t worth seeing the doctor — both because of how quickly the symptoms resolve, and how easy it is to spread norovirus — unless they’re experiencing severe dehydration.

That goes double for children, Handy says.

“[Dehydration] can be very impactful for people with certain medical conditions, for infants, and young children who can’t rehydrate,” she said. “And so those are the folks who might need to come in to either get help with oral rehydration or potentially IV fluids. For children, we recognize the risk of dehydration. Very young children have even more body water than older children, and so they’re at higher risk.”

CHOP has information on its website about rehydrating children when they’re sick — but if those protocols aren’t working, for example, if the child is unable to keep even small amounts of liquids down, it may be necessary to bring them to the hospital.

Other warning signs include fatigue, inability to play, no urinating for eight-to-12 hours, sunken eyes and red, chapped lips.

“For parents, I always say, ‘If you just have a bad feeling or you want someone to check out your child, bring them in so that they can get seen,'” Handy said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.